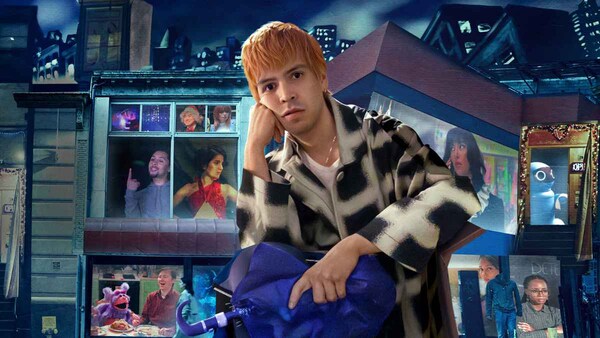

Fantasmas Review: Julio Torres’ wondrously kooky, mischievously unclassifiable show is one of the year’s best

A radically inventive, gloriously queer joyride through late-capitalist identity and representation

Last Updated: 11.47 AM, Jul 14, 2024

It wouldn’t be a stretch to declare Julio Torres’ new show, Fantasmas, as belonging to a thrillingly uncategorizable breed that places little regard in any traditional narrative design. It is an absolute, glorious rejection, even though the version of himself that he plays in the series is buoyed by originary desires of belonging and finding a foothold in the industry. While there’s a great pomposity and parading of diverse representation, ultimately boxes of perception are tough to evade. Studio executives may not be directly and overtly hostile and make gestures of inclusivity that hold no valence and are mere, empty statements. Fantasmas is a free-spirited, rambling and spectacularly defiant odyssey through a world where a hyper-capitalist, relentlessly consumerist, online-besotted gaze traps projections of identity and expression. Reality is always punctuated with fleeting bursts of distractions. Julio Torres captures this onslaught of interruptions aptly as micro-bubbles that pop up in the narrative without cue and vanish as swiftly.

Torres’ familiar grievance with bureaucratic procedures serves as the entry point into this deliriously imaginative show. In fact several seemingly diverging strands stem from his proverbial preoccupations. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. When the New York-set show opens (recreated through sound stages) , Julio is pitching an unusual shade of crayon to executives. He insists on the need for a colour that’s “clear”. There’s obvious bewilderment at the table. In his trademark deadpan style, he explains he can feel the interior lives of shapes, colours, patterns. This is by virtue of being struck by a lightning bolt when he was a kid and got lost in a forest. A recurring feature in all of the director-writer’s work has been a dazzling, provocative and funny dialogue with mundane objects. The humour prises apart even an alphabet, grudging at Q’s awkward positioning and asserting it should have been closer to the kindred unconventional cluster of X, Y and Z. Q comes alive through Steve Buscemi’s embodiment, who mourns the absence of a market for the weird. The misfit-ness of Q, who is constantly rejected, is just one of the many stand-ins for Torres’ extravagantly and peculiarly heightened sense of imagination which has to perennially hustle for more elbowroom.

Julio has to grapple with two crises. One is the escalating urgency to have a “proof of existence”. This has gained rapid importance in governing every aspect of life, from employment to housing. Without it, the individual may as well be a castaway. Julio, disdainful of the regular paperwork required to avail it, is informed by his agent, Vanesja ( a scene-stealingly arch Martine Gutierrez) that celebrityhood would exempt him from the ordeal. Vanesja is actually a performance artist who once played Julio’s agent and just got stuck in the rut of it. There's also his robot assistant, Bibo (Joe Rumrill), which has ambitions of being an actor. It too has to settle for less though it's glad to even function as a prop, when official frameworks interrupt.

Now, the options to achieve that level of fame demand compromises, which Julio does resist but bends to play with while fighting to preserve his own voice and ideals. He is persistently nudged to take up the credit card commercial gig. But he is headstrong about pitching ideas to network bosses. Of course, the one that they want him to do and in which he is least interested is a cheesy, cliché-ridden show on coming out to his Abuela, to get brownie points for diversity.

The other predicament that hovers over Julio is a diamond-studded oyster earring which he loses at a club. He’s determined to unearth it. He’s also convinced that his mole, a birthmark, is getting bigger and may be a tumour instead. The journeys he makes, weaving these issues together, constitute the ground upon which Torres unfurls a whole gallery of what would be usually called minor diversions but here they encapsulate a rich spectrum of riffs on the absurdist chaos of our times. Across the six episodes, there are miniature parodies of SNL/sitcom sketches ( Paul Dano shows up in this strand that takes one of the wackiest turns), a court case of an elf ( Bowen Yang) suing Santa for unpaid labour, the anxiety in the transient influencer culture, an insurance rep ( Alexa Demie) taking wicked relish in not being able to help customers and revelling in slavish work culture. Tilda Swinton ups the ante at the cameo game with voicing toilet water. The show even nods to a gay hamster club, charting its history and giving a chance to Torres to flash his iconic hand acting.

There are no rigid demarcations; everything flows together in a restless muddle in a dense, frenzied simulation of modern life and the vacuousness in its bustle. The aspirational bleeds into every edge of existence but the grime of hard-scrabble strugglers and dreamers are in vivid focus. Actors’ insecurities and guilt find an equal footing here as do their regular fans. But Torres never fails to tickle our fantasies, like gifting us a vision of Dylan O’Brien in red, lacy lingerie.

Fantasmas is filled to the brim with gleeful zaniness. It delights in the unhinged and is constantly driven by a spirit of excess. There’s this incredibly maddening energy heaving beneath the motley strands weaving the show together. In the hands of a lesser storyteller, this could all fall apart. But the unique mayhem of Torres’ mind, his tendency to allow unruly, new sprouts of thematic explorations are held in place by a solid logic of its own. At no point does this curious, ever-expanding, exuberantly lunatic world stretch belief. There are generous sprinklings of fantasy and everything odd, as the ridiculousness peppering the show is grounded in genuine, palpable angst.

Fantasmas keeps leaping among multiple tracks criss crossing into one another and ultimately making a grand coalescence. Perhaps the concluding unifying effort is a little too pat but the shimmer of hope in it is such a delightful re-aligning. The singular, sublime strangeness of Julio Torres’ imagination has no threshold.

Premium

Premium