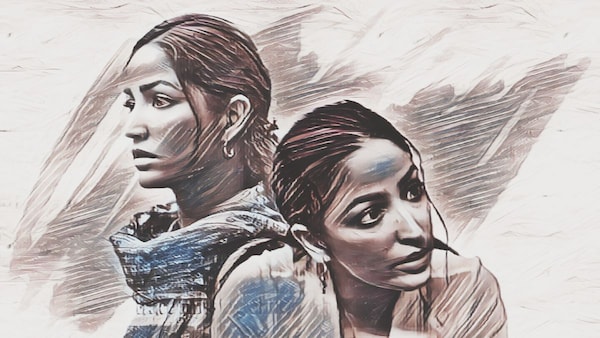

Yami Gautam's 'Lost' Sparks Briefly But Never Quite Bursts Into Flame

Based on the case of a missing boy, Lost has the requisite urgency, but no sieve that separates frothy ideas of journalism from the lived-in complexity of actual people, writes Manik Sharma.

Last Updated: 12.51 PM, Feb 15, 2023

“SHE LOOKED LIKE A SUFFERING ANGEL,” Vidhi Sahani, a journalist (played by Yami Gautam in ZEE5’s Lost), tells her boyfriend about a mother reeling under the loss of her son. It’s an odd statement in a film that often seems detached from the emotional core of the crisis it intends to frame. Based on the case of a missing boy, Lost has the requisite urgency, but no sieve that separates frothy ideas of journalism from the lived-in complexity of actual people. It does, however, have both Pankaj Kapur and Yami Gautam in an interesting grandfather-granddaughter dynamic that nearly rescues a plodding, confused narrative from driving off the cliff into oblivion.

Tushar Pandey stars as Ishan Bharti, a young Dalit boy who is involved with Kolkata’s local street theatre scene. Ishan — an idealist — is in love with Ankita (played by Pia Bajpiee), who has her eyes set on climbing the proverbial ladder. To achieve her ambitions, Ankita seeks the thorny assistance of local politician Ranjan Varman, played by the ageless but also miscast Rahul Khanna. (Varman is supposed to be a soft-spoken but ruthless politician, and while Khanna imports a cushioning grace to the rugged politician we have been used to on OTT shows, he also looks far too manicured and luminous to seem believable.)

On the night that Ishan confronts Ankita about her relationship with Varman, he disappears. What follows is a search led by Vidhi, a self-righteous journalist who is peeved and pressured, but never quite pushed to the brink. She lives with her ‘Nanu’, away from her parents who visit regularly. The specifics of this particular equation are never illustrated in full, and it makes for, perhaps, the greater mystery in the film. The two share case details, food allegories and often confide in each other the way two friends would. In one of the best scenes from the film, Kapur coaches two men in the existential dread of old age that makes him far more dangerous than people with something to lose.

Like most journalists imagined by cinema, Vidhi chases leads and sources through cramped alleys and against good sense. Incredibly, she gets easy access to people placed highly in offices, the red tape sidestepped for the sake of a story that is unclear about the things it wants to communicate. There is journalism happening here, but without the resounding resistance most journalists face from people unwilling to cooperate. It’s an everyday nightmare, but in Lost it simply doesn’t exist. To add to that, there is no socio-economic consideration to mull, for journalism — at least investigative journalism — has become a financial risk that most people in the country would rather not take. Vidhi, in that sense, appears privileged and cocooned, even if unglamorous in a superficial way.

Most of the cast delivers. In fact, Gautam is convincing as a feisty and naïve Vidhi. She doesn’t quite possess the bullishness of seasoned scribes but doesn’t succumb too easily either. In one scene, after she receives a threat, she hastily dons a scarf and sunglasses — while sitting in her office. The dramatism of this moment is unfortunately too loud to land. Had it been subtly infused into the film, it would have worked better. To which effect, as much as this film can imagine moments that crackle with potential, it doesn’t have the competence to actually fit them to the genre’s grammar.

Directed by Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury (Pink), Lost momentarily flickers but never quite lights up the screen. There is a hint of caste politics, love, betrayal and cronyism, but never the sense of an actual mystery brewing. Strangely, almost the entirety of the film unfolds within walled spaces rather than the streets where crime scenes have a kind of kinetic energy. Instead, everything stands still until one block of dialogue hits the other, urging pained actors to drag a sluggish narrative forward.

There is a moment in the last half of the film when Vidhi speaks to a Maoist leader over a video call. She looks as perplexed as her questions feel under-cooked, atrociously inarticulate and naïve. It’s also where the film eventually crashes and burns and in doing so, belatedly offers the sight of a crime scene. The crime: Of depicting neither journalism nor mystery to their full potential, while flanking it with intriguing assets like Rahul Khanna, Pankaj Kapur and Yami Gautam herself. Most of these actors are in their element and Gautam continues to shed her bubbly, incandescent self for roles that demand a stripped-down earthiness. But for all her endeavour and commitment, the writing fails to match her ambition. Here, she walks through alleyways flummoxed by a mystery that won’t yield to her doggedness, and where the script and direction are of no help either.

Premium

Premium