The Holdovers: When 'Making Do' Is Your Only Shield Against Grief

In The Holdovers, fate conspires to bring oddballs on the brink of oblivion, together — and then there’s no turning back. But the real world is too unsparing to allow such bittersweet contrivances.

Last Updated: 11.52 AM, Mar 10, 2024

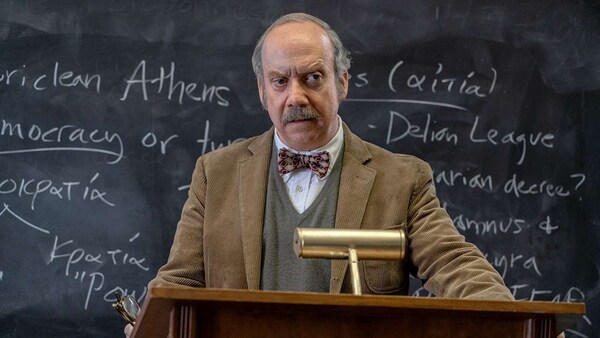

ALEXANDER PAYNE’s The Holdovers stars Paul Giamatti as Paul Hunham, a crabby middle-aged professor at a private New England boarding school in the 1970s. Nobody likes this man. But his personality seems to have been combed from years of deep-set decay. He has a lazy eye, an addictive sense of solitude, and a body odour problem; he lives alone, and almost looks forward to his own performative sass during classes. In a parallel universe, he is the colourful villain of a Patch Adams (read Munna Bhai M.B.B.S) or a Dead Poets Society (read Mohabbatein). He spreads the opposite of love and kindness. Paul derives perverse pleasure out of torturing and disciplining his students, most of whom belong to wealthy and influential families.

When he ruins the Ivy League prospects of one such son of a donor, Paul’s punishment is to babysit the ‘holdovers’: a few students who — with nowhere to go for Christmas break — are left behind on campus. One of them is Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa), a troubled teenager whose mother is busy holidaying with her new beau. When the other students get picked up by a jetsetting father, a bristling Paul and Angus remain, along with Mary (Da’Vine Joy Randolph), the African-American cafeteria manager whose son recently died in the Vietnam war. The narrative journey is familiar. This unlikely trio — all of them broken in their own ways — finds hope and healing in their time together. Their misery-loves-company chemistry morphs into a bond of makeshift companionship.

At first, the two adults have every reason to be triggered by the kid. For Paul, Angus symbolises the entitled young brat who accused him of plagiarism, got him expelled from Harvard and ruined his career all those decades ago. For Mary, Paul represents the privileged white brats who use education as an escape from military recruitment while her own son enrolled in the army to afford the fees for this school. Yet, Paul and Mary overcome their own biases and resentments to serve as de-facto parents: Mary often scolds Paul for scolding Angus, while Paul sees Angus as his chance to go back in time and dismantle his own demons. It’s not exactly a cuddlesome threesome, but the cobbled-up warmth is Payne’s trademark antidote to pain.

When I watch movies like The Holdovers, I always feel a tinge of envy. Serendipity plays such a big role in these stories. Somehow, lost souls find each other at the right time and right place. Fate conspires to bring oddballs together on the brink of oblivion — and then there’s no turning back. But the real world is too unsparing to allow such bittersweet contrivances. I’ll tell you why. Manchester By The Sea made me miss my childhood with an uncle who eventually lost his way. It made me wonder if, ironically, it’d have taken a family tragedy to yank him out of his emotional wilderness. Perhaps if my parents had died young, the responsibility of being saddled with a teen nephew might have forced my uncle to grow up, exorcise his ghosts and honour his late sister.

But my parents were always around. Sometimes, too alive. As a result, he was never allowed to become the protagonist. In a way, their failing marriage denied us a few flights of alternative fancy. The story with my uncle never unfolded — it fell through the cracks of anti-providence. The scruffy relationship between Paul and Angus is similar, but note the series of smaller coincidences that lead them to each other. That is storytelling. If Angus wasn’t on campus, Paul would have never become the central character. If another teacher was chosen to supervise the teens, Paul would’ve never undergone the transformation that he does. That’s how close Paul is to never seeing the light. That’s how close imagination is to the absolute realms of reality.

The beauty of Giamatti’s performance is that he plays Paul Hunham as a griever. Paul acts like the pall bearer of his own coffin. The man is grieving — while at once carrying the weight of — his previous self. Paul lost his future at a young age. It’s a profound loss, and one that’s made him so afraid of suffering again that he learns to make do with a lesser version of living. He accepts the bargains and toxicity of a diminished adulthood: An arrogant headmaster who was once his student; perennial bachelorhood; a life of revenge against the Americanisms that wronged him; students who hate him; a faculty wary of him.

Paul’s petty purpose is a coping mechanism, but it’s also rooted in the economic dysfunctionality of human nature. His grief puts him in perpetual “something is better than nothing” mode. That’s why he tries to salvage his second-rate existence: This wasn’t the plan, but at least he still has a job, an image, and a distorted sense of value and intellectuality. Navigating the vacant halls — and not the cold wilderness — is a more merciful fate.

It’s also why Paul empathises with Mary, another griever left on the campus-fringes of society while everyone else is on vacation. They have nowhere to go, and they’ve embraced all sorts of darkness — smoking, drinking, low wages, high tempers — under the pretext of survival. By the end, Angus becomes Paul’s catalyst to puncture this holding pattern of poor self-esteem and compromised dignity. Paul realises that he doesn’t have to keep settling for a life that simply allows him to live; he can finally reach for a life that lets him thrive. When he leaves with a flourish — telling off his boss and driving away with expensive cognac he doesn’t need — Paul is an evolved holdover. He isn’t waiting for everyone to return and the term to begin again; he is setting out to reclaim his own terms.

Earlier, I’d watch someone like Angus and romanticise him — the kid who receives guidance before it’s too late. Now it’s the cantankerous Paul who makes me feel seen. It’s strange how we find our reflections in the most unforeseen corners. Like Paul, I’ve been grieving the demise of my former self. I lost my closest friend last March, and I’ve been struggling ever since. Every day has been an uphill battle. I’ve been stuck in a cycle of acerbities and adjustments. The shock of looking into the void has also made me more tolerant — and indulgent — towards the few friends I have left. I keep telling myself to be grateful for some presence, any presence, whether good or bad. With nowhere to go, I have tried to ‘manage’ with very limited equations. There have been instances where I’ve made concessions for the whims of lesser people because I’m afraid of losing further. Even worse, I’ve been acutely aware of this weakness — this balance-sheet fragility that has forced me to accept circumstances and be trapped in an endless state of damage control. I dare not demand more.

And then I’ve pondered: If I were in a movie, this is when a chance experience with a stranger would’ve rescued me from my reduced world. I’ve craved the magical intrusions of fiction. But The Holdovers happened to me while I was busy making other plans. I watched it at the end of December, and didn’t expect anything more than a mature Christmas movie. I enjoyed it and moved on, convinced that it was too slight to leave a lasting impression. But over the last few months, it has slowly altered my system without me quite realising it. The film has bled into me, empowering me in small but necessary ways.

For instance, an unpleasant incident occurred on New Year’s eve. An old college friend — who had, in time, become an unhealthy habit in my life — invited us over to his apartment. After midnight, totally unprovoked, he started to misbehave with a guest. He said the cruellest of things, venting on the docile guest and flaunting his empty masculinity. It wasn’t just a drunken rant. He accused him of being a freeloader, mocked his financial status and bullied him out the door. What he was really doing was throwing a tantrum because his loved ones — his wife, his mother, me — had often let him get away with it. None of his misplaced rage was directed at us, but it compelled me to take a stand. It pried open my eyes to the entitled brat we had been indulging for years, only because he was funny and a hit at parties. “He’s flawed but he means well,” they — and we — said. He even disarmed everyone by admitting that he was a jerk who was fortunate enough to be surrounded by kind folks — and that, for better or worse, we had all chosen each other. That was how he gaslit his environment into enabling him.

This night became my chance to finally cut him loose. There had to be consequences. When I confronted him about this behaviour, and especially his reluctance to engage with me in the last year, I will never forget his callous response. He said he was ‘scared’ of being there for me and my grief — he didn’t want to shoulder the burdens of being an unconditional friend — and so he consciously avoided me. He only wanted the betters — the weekend trips, the drinking sessions, the Diwali parties — without the worse. I walked out on him, feeling a lot like Paul who quits with a final insult to the toxic school principal. I exited all our shared WhatsApp groups, too, aware of the price of upholding my own principles — and self-respect — in this age of digital connectivity.

But I feel lighter today because, for once, I’m not modulating my expectations anymore. I’m not merely making do anymore. The holding pattern of staying connected to self-serving individuals and being at the mercy of their calibrated charities — only because my wounds are too raw — is broken. I know that he compensates for being a selfish guy by being a selfless son, but I can now tell the dark holes from my galaxy of imploding stars. I don’t need to put up with something for the fear of nothing. I don’t have to trade my vacuum for the plastic parameters of social agency.

Ironically, it’s a film that became the serendipitous fiction — the Angus, the Mary, the road trip, the quirky get-togethers — I didn’t know I needed. Its hold over me has emerged in the knick of time. I may not know where I’m driving off to, but at least I’m no longer punishing myself in the throes of regulated morality. Just like Paul Hunham is cured of his cynicism by the vulnerabilities of a young student, I’ve been cured of my self-doubt by the vulnerabilities of a vintage Christmas movie. Maybe I can write that metaphorical monograph — a memoir in my case — without being held hostage by my history. Not to mention the privileges I’m still fortunate enough to possess: My parents, my partner, some compassionate new friends, a job I enjoy, and of course, memories of my late companion. There is no happily ever after, but there might be an after. There is no end to the grief, but there might be a brief — a blueprint — for a belated beginning. Being a holdover isn’t so bad after all. You hold onto white noise until you’re over the silence, but you’re actually erasing the noise to hold sway over the fluctuating silence.

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of OTTplay. The author is solely responsible for any claims arising out of the content of this column.

Premium

Premium