The Anubhav Sinha Interview | 'I'm Alleged To Be More Political Than I Am'

Post-Bheed, Anubhav Sinha talks to Subha J Rao about the philosophy that guides his filmmaking, the world he inhabits, and why he keeps going.

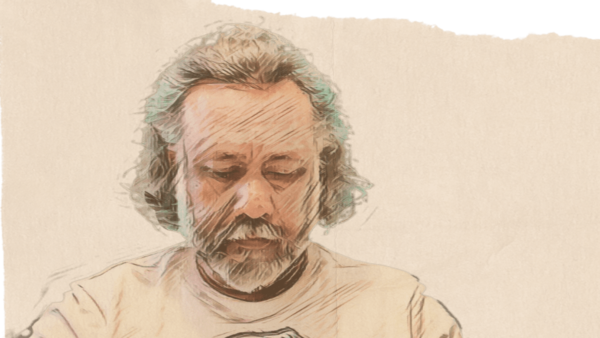

'Sometimes, the box office result is discouraging, but the love and respect I receive is outstanding,' says Anubhav Sinha

Last Updated: 10.26 AM, Apr 07, 2023

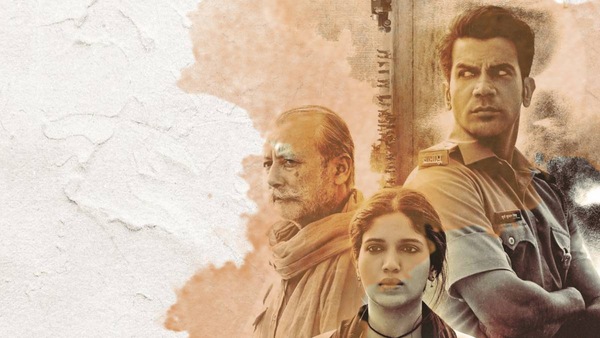

Anubhav Sinha’s Bheed, searing in black-and-white, is a sort of collective conscience asking us to open our eyes to what happened over March and April of 2020, after the first nationwide lockdown was declared in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The film, starring Rajkummar Rao, Bhumi Pednekar and Ashutosh Rana, among others, puts regular folks and the police force in a situation that no one expected to be in, and turns observer as casteism overrules hierarchy, as basic decency initially recedes into the background and prejudices take over, and as characters discover their inner strengths. It is not a blame-game, but a film that seeks to tap into everyone’s empathetic core.

In a conversation with OTTplay, Anubhav spoke about his film philosophy, making the move from commercial films to the new world he inhabits, and more. Edited excerpts:

In a sense, Bheed seems like a continuation of the world you and Manoj Bajpayee created in ‘Bambai Main Ka Ba’, which spoke about the plight of migrant workers.

Possibly, yes. I was very affected by what I saw in the initial days of the lockdown. And that was when Dr Sagar [the lyricist] sent me this phrase: ‘Mumbai mein ka ba’. I loved it, and in two days, he had written the entire song. Manoj usually calls me on the way to shoot — he’s very good at staying in touch. In two weeks, he had finished recording for it. That song fulfilled this urgent need in me to react to what was happening around me. But there was more that stayed with me. And that is Bheed.

For some years now, your creations have taken a strong social and political stand. What was the trigger for that change? And where is the space for a filmmaker like you?

I am alleged to be more political than I am [laughs]. I am in a very different space, because I also come from a background where I have made Bollywood potpourri, with song and dance and action sequences. It feels like a very organic obvious choice to move to where I am today. My heart keeps pulling me towards where I am, and money keeps telling me to go back to what I was. Now actors are kind enough to work with me… This is a choice I’ve made. And then, when I have an under Rs 2 crore-weekend, my heart breaks. Then, I speak to myself, train myself to look at the reviews and the messaging.

Even with Bheed, people are writing paragraphs on Facebook. In the long run, that’s dividend enough. Every film will find its audience.

My films usually tend to live long and travel slowly through the years. Mulk was a reasonable success at the box office. It’s been five years since Article 15, but the way people talk about it, it feels as though it released last year. Thappad has its audience too. Anek did not get as much love though.

How difficult was Bheed for you to make, considering you were recreating a very brutal migration that happened just a couple of years ago?

It was a very difficult process, and the folks who worked the hardest were my assistants who put in months of effort. They had to look at images that came out in the media, analyse them, see what made them striking and then recreate all of those images. They would make notes about the characters, reason out what made them striking, and this went on for a long time. We cast about 100 people for the crowd, and they were non-actors who were trained by my assistants.

How easy is it to get actors to be a part of your films, considering the current atmosphere in the Hindi film industry, where anything critical is frowned upon?

They trust me, I guess. I send the script out, and they offer to be a part of it. Actors are even willing to play smaller parts compared to what they do normally. And I end up making an ensemble film of sorts, with no heroes or heroines but various characters. They stand by me, and they amplify my voice. It is a leap of faith, and that makes it interesting and fulfilling.

At what stage of prep did you decide to shoot the film in black-and-white?

Halfway through, we were still writing the film, and one day I got this idea and bounced it off the team and everyone was excited. I saw the movement of people post-lockdown as an epic tragedy, and Soumik Mukherjee [the cinematographer] and I were struggling, wondering how to make it look like one. This idea of keeping things in black-and-white felt right. We kept struggling to articulate the film as we felt it, and this settled it for us. Yes, it is a difficult watch, but we hope the theme will nudge people into going and watching the film, and that it will possibly tap into their conscience.

Do you see this as your most important film so far?

This film is very important to me. Because I see it as a documentation of something terrible that took place.

How did you react to the stories that hit our collective senses, post-lockdown?

With a lot of horror. I saw a lot of apathy. Very few people were out on the streets, helping. It was very disturbing and I wanted to see more hope.

Is Gitanjali (played by Dia Mirza) in the film most of us?

Ah, I know a lot of Gitanjalis; maybe I am one of them too. Just that I stepped out of the car a little earlier. During the early days of lockdown, I would drive on near-empty streets for cigarettes. I’d see only expensive cars on the road. I did not wonder how the cigarette seller was able to sell, where he came from, was he eating? It was me and my cigarette. And then I got out of the car.

Bheed underwent some cuts due to the censors. What are your thoughts on censorship?

My thoughts are that the way the Act was written in 1952 is quite open to interpretation. Law actually is, otherwise courts won’t exist. You have to believe in the law of the land. Sometimes, you may be dissatisfied, be wronged, be disillusioned, but it’s maybe, the individual then. The good news is that all my films have released with a UA certificate, and they’ve released! But, yes, I think the CBFC should be a little more tolerant with art. It’s art! It’s not going to change society or government or the legislation or the judiciary. At the end of the day, art can only pose some questions, and those questions should always be allowed better.

Your films don’t shove casteism, overt or subtle, under the carpet. When did you become aware of caste and its tentacles?

I think from Article 15. I knew I was privileged, and never knew whether I was upper caste or not, because I do not belong to any of the four varnas. But as far as I can remember I was always treated as upper caste… Caste never affected me. When I started working on Article 15, I started reading about caste. I read Ambedkar, I read the very effective Joothan, Om Prakash Valmiki’s autobiography. Then, your eyes start opening up, you realise your privileges, and things you haven’t had to deal with. This awareness is still growing inside me, and I am not done with it as yet. You see a more nuanced caste conflict in Bheed and in times to come, you’ll see even more.

From Tum Bin and Ra. One to Mulk, Article 15, Thappad, Anek and Bheed, when did the switch to social consciousness happen?

I think it began with Mulk. I deeply cared about it, and it was my reaction to the metamorphosis in society. I needed to stand up and say something and I realised I found my voice. And then, I found a reason as to why I wanted to make these movies.

I have evolved as a person and I continue working on it. Sometimes, the box office result is discouraging, but the amount of love and respect I receive is outstanding. At the end of the day, all I want is to talk to people. I hope I can continue to talk to more and more people.

Amid such a scenario, how do you hold on to hope in humanity?

Do you have a choice? We have to co-exist, and all you can do is to consistently fight disparity. And to be able to fight, you have to hope that you will win. I know this war will never be fully won, but we can win small portions and take ourselves to a place where it is bearable. Right now, it is unbearable.