Newsletter | Vadivelu Is Maamannan, & Maamannan Is Vadivelu

If there’s one thing Maamannan will be remembered for, I hope it’s for Vadivelu and a long second innings that should follow, writes Aditya Shrikrishna.

Last Updated: 02.32 PM, Jun 29, 2023

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on June 29, 2023. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

EVEN before the release of Mari Selvaraj’s third feature Maamannan, the film suffered a huge disservice. The conversation after the director’s speech at the audio launch — during which he cited Thevar Magan (1992) and how Maamannan was not merely a reimagination of its central conflict but also inspired by it at a formal level — turned into feverish cacophony. What was said, how it was said, what was right and wrong about the director’s speech… the discourse followed the by-now-familiar news cycle of everyone weighing in with their opinions whilst reevaluating a famous work in Tamil cinema. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

But what people seem to have lost in this debate is the little fact that this is Mari Selvaraj’s film. What about this film? What does it say? How does it say it? When conversation about the film even before the release is all about comparison, one can only imagine how reductive the discourse could become after watching it. Maybe people should listen to Thiagarajan Kumararaja when he says ‘do not talk to creators’.

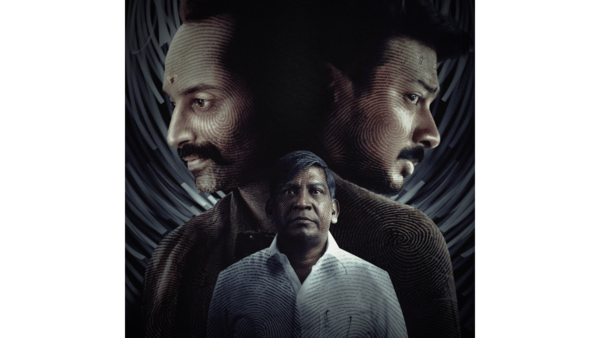

Vadivelu is Maamannan and Maamannan is Vadivelu. Initially a party worker (a party with social justice and equality in its name) who is groomed by one of the leaders (with little belief in the words in that name), Maamannan happens to be a tool for the party at the right time — an electoral candidate in a possible reserved constituency. The film begins with the juxtaposition of what it is about: Two sons and the legacies and values they formed or inherited. We switch back and forth between a day in the life of Athiveeran (Udhayanidhi Stalin, miscast as always) and Rathnavel or Velu (Fahadh Faasil, beaming intensity as always).

The former, son of Maamannan, rears pigs and is not on speaking terms with his father, an arrangement the father and son have a huge respect for, which gives away the latent but unperformed mutual admiration. Meanwhile, Velu’s father Sundaram is the leader under whom Maamannan came into his own in the party and he is non-existent today, it’s only District Secretary Velu who runs the show with his wild dog races and often unsuppressed anger. Maamannan is replete with Mari Selvaraj’s signature imagery; the animals here like dogs, pigs, piglets are all there but it’s also not a great world for them. It’s a difficult movie for animal lovers, there is more violence inflicted on innocent fauna by the bestiality of man than what we are used to in cinema — mano a mano.

What Mari Selvaraj — writer and director — does best in Maamannan is establish characters, their historicity and motivations. A quick monochrome flashback reveals the story of the father and son, who is only physically present but mentally checked out of the home decades ago. A son on the run is the theme of this short story and the filmmaker links past and present with a shot and sound of a train chugging along. His visuals are now tropes — rocky landscape, hillocks with little to no vegetation, and cuts to dreamlike shots of bloodied characters sporting different levels of injury. As he has often demonstrated, the filmmaker is interested in documenting pain and suffering and the trauma they contain through future generations.

Maamannan might have gone from a hut to a house with a gate and a tiny courtyard, but he keeps returning to the barren cliff where he first wept for his son (the strings version of ‘Uchanthala’ elevates this already great moment and the song itself infuses energy later when the film runs out of it). This is not a film where the father passes something to the son. This is more about the son teaching the father newer ways to resist and fight back. Its staging, dialogues and scene transitions produce this liminal effect, moments pregnant with anger where Vadivelu’s Maamannan comes around to the ways of Athiveeran and apologises for going down a different road.

Maamannan is also about the politics within the party. Mari Selvaraj’s central question here is clear — can the people of the oppressed caste ever co-exist and work together in an established political party with a long history of espousing one ideology on stage and another on the streets? In Maamannan, it is literalised due to plot mechanics, whereas a film like Sarpatta Parambarai (2021) metaphorically dealt with the same with more panache, bravado and success. Maybe due to the casting of Udhayanidhi Stalin — a sitting MLA — or some hesitancy on Mari Selvaraj’s part, the film crawls its way out by painting Velu as a bad seed in a party headed by a more statesmanlike Chief Minister.

Sure, the film is about these specific characters but when one is trying to take a larger worldview, it seems to treat its tormentors with kid gloves. It’s also what causes Maamannan to fall through the cracks: Once we get into election territory, a game of one-upmanship begins, and the film loses its virility to give way to flaccid eventless sequences that only serve as means to get to the end. An elaborate but insipid news channel debate with chief ministerial candidates’ caricatures floating on the sides of the screen is the last thing I expected from Mari Selvaraj.

After actors like Kathir and Dhanush, it’s tough to consider Udhayanidhi as a Mari Selvaraj hero. The man tries hard, but his face and eyes can convey only so much for a film full of scenes where his Athiveeran must pack fists of fury. It doesn’t help that the two actors pillaring him are Vadivelu and Fahadh Faasil, the latter effortless as the antagonist even in an underwritten role and the former nonchalant in his switch from comic to a dramatic turn where he is calculated in his movements, the use of his hands or how he behaves in different rooms.

Some of Vadivelu’s best scenes are in the beginning of the film when he meets his party workers at home or when he receives Leela (Keerthy Suresh, another thankless role that is derived solely from all the message-heavy t-shirts she wears) and her friends. When he gestures to others to sit in front of him or his solemn lungi-clad self when he witnesses destruction, Vadivelu does a lot with little. If there’s one thing Maamannan will be remembered for, I hope it’s for a Vadivelu and a long second innings that should follow.

Premium

Premium