Love Storiyaan: An Imperfect Ode To Relationships That Defied The Odds

Love Storiyaan is proof, albeit not the most persuasive one, of Karan Johar's progressiveness as a producer.

Last Updated: 04.20 PM, Feb 14, 2024

LOVE STORIYAAN, the uneven new outing by Dharmatic Entertainment, comes at an opportune time. The six-episode anthology draws from real-life love stories put together by journalists Samar Halarnkar, Priya Ramani and Niloufer Venkatraman — the architects of India Love Project, a storytelling endeavour that documents and aids unconventional (interfaith, inter caste and LGBTQ+) love. Back in 2020, it was created as a sobering reminder of the pluralist fabric of the country amidst religious hegemony. In the last four years, the hostility towards such partnerships has only risen, thus warranting the need for a reminder.

In more ways than one, Love Storiyaan is that. It is a documentary that trains the camera on people who braved societal odds to be with each other, and through their lives revealed the redundancy of criticism reserved for them. It is a reiteration of the joy of partnerships that refused to subscribe to norms and underlined that love, at its core, is rebellion. It is a homage to the many who fought with their lives for love and were emboldened to put up a fight because of love. It is timely and necessary — and it is also not enough.

This is not to say that the venture is a lost opportunity. Instead, it culminates as an instance of the makers not mining the full potential of such an opportunity. Conceptualised by Somen Mishra, Love Storiyaan brings together six filmmakers (each short shares two writing credits) with unique sensibilities. Their work is largely watchable and leans more towards better than bad. Yet, the anthology ultimately accumulates the legacy of not matching the audacity of the couples — and their love — it chose to feature.

A large reason for this is the format Love Storiyaan chooses, wherein the stories of love are depicted as storied love. In other words, most shorts look at the couples through the lens of the conflicts they had to overcome, thereby defining them by their adversities. Take for instance the almost soap-opera aesthetic with which each opens, designed to bring to light the “problem” in their story. The one centring on a transgender couple (titled “Love Beyond Labels”'; directed by Collin D'Cunha and co-written by him and Soumyajit Ghosh Dastidar) begins with a recreation where a young boy longingly looks at married women.

Things are no different for “An Unsuitable Girl”, the first short (directed by Hardik Mehta and co-written by him and Mirat Trivedi). It chronicles the story of Delhi-based editor Aekta Kapoor who met and fell in love with Mumbai-based author and journalist Ullekh NP after her divorce. Their relationship was disapproved of by her youngest daughter but things took a turn for the better when they adopted dogs. It is a heartening tale which underscores how reconciliations can lurk in the unlikeliest corners. Yet, it starts off with a (recreated version) moment of an online chat where the girl bashfully tells the boy that her colleagues are teasing them of having an affair.

Like a lesser fiction, several outings in Love Storiyaan unravel being attuned to the presence of the camera. There is a tendency to eke out a three-act structure which results in the featured stories concluding with a force-fitted ending. Mehta’s short, the weakest in the anthology, ought to be mentioned in this regard. “An Unsuitable Girl” takes an affirming tale and ends on a facile note where Aekta and Ullekh visit the latter’s ancestral home in Kerala. The implication is that something like this was happening for the first time since their marriage, especially with the daughters involved. But this idea of a homecoming feels too curated and unbecoming of the non-fiction genre.

Ditto for the second short, “Love On Air”, which is directed by Vivek Soni (the filmmaker of Meenakshi Sundareshwar). It tracks the love story between two rival radio jockeys in Shillong, Nicholas J Kharnami and Rajani Karki Chhetri, which was sparked by a star-crossed prank call. The interfaith couple (she is a Hindu and he is a Christian) had more problems along the way. Nicholas was married before, and had addiction-related issues. This is an intriguing story, held together by three people. Rajani had prank-called Nicholas because his dedicated listener, Mandira, had asked her to do so. As it turns out, Mandira is blind. It is a fascinating assertion of fate, better than most invented narratives. But Soni, much like Mehta, barely scratches the surface. He is too content to ask them cursory questions and angles for a contrived ending like he is packaging a Humans of Bombay episode.

Even the form is uninspired, comprising talking heads, old photographs (depicted through varying aspect ratios) and recreations. In fact, dramatic recreation is a persistent problem across the anthology. All filmmakers use them, some more than others, that not just robs moments of their potency but also hints at their lack of faith in the story at hand.

These problems persist in the last four shorts but they are imbued with the merit of the non-fiction genre. Each in their own way hints at the joy of watching documentaries when it is not geared to evoke engineered emotions. Take for instance “Raah Sangharsh Ki” by Marathi filmmaker Akshay Indikar (who earlier helmed the terrific Sthalpuran), co-written by him and Tejashri Akshay. It documents an intercaste marriage where an upper-caste Bengali man, Rahul Banerjee, is wedded to Subhadra Khaparde, a woman from the Dalit community. In spite of the social tag of a transgressive arrangement, Indikar follows the couple to depict that this is an equal partnership. They work for the upliftment of backward communities and empower each other.

Indikar conforms to the sanctioned form (the short opens with a dramatic recreation indicating something that it never addressed again) but he also allows the people in the frame to be. They retell their past with candid frankness (Rahul’s mother was particularly against the marriage and Subhadra hilariously recounts that despite the ill treatment meted out to her post marriage, she enjoyed wearing new saris and being visited by people) but there is a particular moment that arrives without notice. Rahul states that he has Psoriasis, an incurable skin condition and many years ago a doctor had advised that he should make peace with it like it is his first wife. At this point, he jokingly says that people tell him that “the Adivasis are my first wife”. Subhadra calls him out immediately, albeit lovingly, for using that word. This singular instance is so unvarnished and effective, so telling of their companionship that it brings to focus the futility of scripted crutches.

Both Archana Phadke’s “Faasley” (co-written by her and Arya Rothe) that trains the lens on an interfaith marriage, and D'Cunha’s “Love Beyond Labels” incorporate the big studio demands (more dramatic recreations and voice overs that sound rehearsed) but stand out as compelling works of nonfiction. The stories are extraordinary, doing most of the heavy-lifting. Phadke’s short documents the lives of Dhanya and Homayon. He is from Afghanistan and she is from Kerala. They met as students in Russia and fell in love. After initial objections from her family, they got married in India. A fictional story would have ended here but life works out in different ways. When Homayon visited his family in Afghanistan in 1997, the country had come under the control of Taliban, the militant nationalist outfit. He was unable to come back. Not one to back down, Dhanya took a 15-day visa and made her way to a war-torn country to be with her husband.

Phadke is gentle in her approach, cogently using talking heads and archived pictures from the time of their stay in Afghanistan. It is a heartwarming excursion that separates religious extremism from people, a fitting reminder if there ever was one. “Love Beyond Labels” is also infused with resilience. It follows Tista Das and Dipan, a transgender couple in Kolkata who scripted history by becoming the first married trans couple of West Bengal. D'Cunha’s gaze stays on the couple as they recall the hardships both had to overcome, through gender-affirming surgeries.

But their candour is such that they refuse to be restricted by their struggle. Through their conversations, Tista and Dipan outline the joys of companionship that go beyond social trappings. There is a bit where Tista, who works for other transgender people to ease their journey, says that every person has an activist in them. When one fights for what they want, that side surfaces. Without so many words, her observation makes a riveting case for love and reasons why those fighting for it, do in the first place. “Love Beyond Labels” is the only instance where the dramatic excess melds into the tonality of the short in conclusion, making a case for the makers’ deft control.

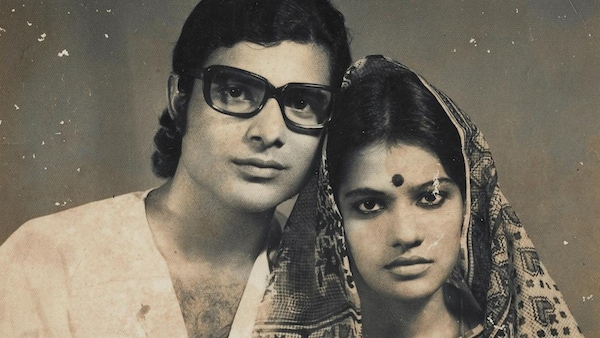

But it is Shazia Iqbal’s “Homecoming” (Rahul Badwelkar shares co-directing credits) that truly stands out, making the anthology better by a mile. It is a tremendously evocative short that probes without being gratuitous, depicts without being showy. Iqbal takes all the accessories of fiction, right till the three-act structure, and transforms them into affecting pieces of nonfiction. It chronicles an old couple in Kolkata, Sunit and Sharmila Saha, who were originally from Bangladesh. Before their marriage Sharmila was a Muslim and both their families had opposed the union. So, in 1973, right after the Liberation War (1971), the young people fled to Kolkata hoping to live in a place where religion will not define them.

There is much to admire in Iqbal’s short, foremost being the affection the couple continue to share. They are the oldest in the anthology and yet their love, that survived filial resistance and deaths of children, drives the point of the outing more emphatically than the rest could do together. Take that moment for instance where Sharmila rests her head on Sunit’s lap and the latter blushes and says that he will charge for it. There is nothing fabricated here. Not even the trip they make to Dhaka at the end after decades to reconcile with what remains of the family. And not even the time when Sunit wipes off Sharmila’s tears when she sees her kin.

Iqbal is particularly sensitive here without compromising on intent. She follows them around when the couple visit their university, the rooms they used to live in during that time. Then Sharmila goes to visit her aggrieved brother. The latter has aged, his gaunt face bearing only flashes of belated grievance. It is a charged moment that the filmmaker does not, for once, exploit for a storied ending. In fact, the short does not record the next time the families meet, stating that the people wanted it that way. There is respect here, there is also empathy. That Sunit and Sharmila frequently converse in Bengali conveys the ease of Iqbal’s presence and her objective to be a bystander, like most nonfiction makers set out to be. With no exaggerated flourishes, Iqbal restates a simple point: if homecoming is a sign of love then love is about coming back to a person who feels like home.

It makes sense that Dharmatic Entertainment, the digital arm of Karan Johar’s Dharma Productions, has backed Love Storiyaan. It is an addition in the long line of clutter-breaking work Dharma has been trying to do. But more crucially, it falls in line with Johar’s inclination towards love stories. Some of the outings in the anthology are more subversive and transgressive than his feature films but he has always been a more progressive producer than a filmmaker. Love Storiyaan is a proof of that but not the most persuasive one.