Kuda Bux: The Real Mystic Behind The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar

The story of how a young man named Khudah Baksh became “Kuda Bux”, a magician whose feats wowed the West, is as intriguing as Wes Anderson's adaptation of Roald Dahl's tale, now on Netflix.

Last Updated: 12.08 AM, Oct 10, 2023

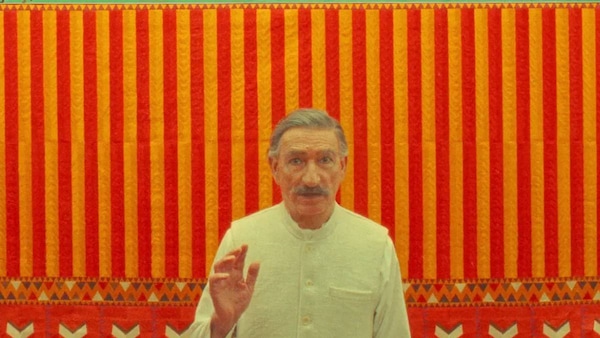

IN 1938, Robert Ripley took his radio show of oddities from around the world to Manhattan’s Rockefeller Centre. Two pits of fire held centrestage, as people converged in awe to witness a turbaned man hurriedly hop through the flames twice. The event would later become the TV show we know as Ripley’s Believe it or Not. The man who walked through the fire was Khudah Baksh*, an Indian mystic from Kashmir who had by then become a bit of celebrity for doing the unthinkable … or at least the inexplicable. “Attending physicians examined the fire-walker's feet, found only one small burn where a coal had stuck to his sole, (and) marvelled,” a report published in TIME magazine said about Baksh’s exploits. Baksh is now the subject of Wes Anderson’s The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (Netflix; starring Benedict Cumberbatch as the titular protagonist, and Sir Ben Kingsley as Imdad Khan, the character modelled on the mystic), an adaptation of a Roald Dahl story.

Baksh rose to prominence, or popularity you could argue, in an era where colonialism was the default lens. Western reporters, litterateurs and travellers sent dispatches back to their homelands, about the folksy ways of the Indian subcontinent. You’ll easily find newsreels from pre-independence India that view the subcontinent as a land of exotic mystics and snake charmers. ‘The Great Indian Rope Trick’, for example, is a totem of western fantasy meeting subcontinental patronage. But Baksh was perhaps different. Born in 1905 in Akhnoor, Kashmir, Baksh travelled across the subcontinent, before finding succour with a yogi in Haridwar. Yogic techniques he learned during this time, Baksh claimed, were behind the virility that allowed him to perform herculean magic tricks. His audience, Baksh knew, lay abroad. And so Khudah Baksh became “Kuda Bux”.

Western rationalists and myth-busters swooned at the sight of a blindfolded Bux effortlessly reading letters, lighting cigarettes and avoiding bumping into slight objects as part of tasks. Tests would be conducted, challenges extended and competitions arranged as Bux carefully dallied with doubt and illusion. For he became popular not just in the awestruck eyes of the western observer — he mesmerised them in their own backyards. The walking on fire trick was executed repeatedly across the Atlantic, with Bux so convinced of his fame and prominence that he bicycled through the streets of London blindfolded, to advertise his shows. Ever since the fire-walk at the Rockefeller that had left the audience bemused and dumbfounded, Bux had ridden the wave of intrigue and doubt, candidly batting denial and suspicion with tactical sociability. People argued about exotic techniques, gaps in the bandages or hypnotism of sorts, but walking on fire was as blunt an undressed trick as magic tricks come.

By the 1950s, Bux was a firmly established showman across the Atlantic despite the occasional report or expose of him peeking down his nose, failing under scrutinising circumstances inside laboratories, and so on. Bux was as much a creation of the media, as he was a darling of the mind that wanted to believe. Naturally, he knew how to play both. Changing his name to an Anglophone spelling was only part of the trick. In 1950, CBS gave Bux his own TV show, titled Kuda Bux Indian Mystic. He performed various acts of illusion and yogic prowess but his most contested and hotly debated ritual remained the one that gave him the title ‘The man with the x-ray eyes’. In 1953, Bux met writer Roald Dahl for a profile that would 70 years later become the subject of a Wes Anderson film.

Bux’s exploits have been as widely reported as they have been suspiciously ridiculed. With time, it possibly became clear that the man was merely a master handler of intrigue as opposed to an inventor of an indigenous science. His methods were anecdotal, unsupported by the consistency of other yogic methods and though Bux candidly played into the hands of a colonial image, it was his showmanship, his ability to create an amicable self-image, that sustained his fame over decades.

Bux performed his eye trick into the last years of his life in the 80s. Do a trick twice and it becomes a rumour; repeat it enough times and it becomes a myth. When it comes to culture, the literature around Bux’s methods, the audacity of his tricks embellish the idea that magic to that specific age carried the appeal of a visual miracle. With scant documentation and evidence, mythmaking was synonymous with storytelling — a fact Anderson’s typically quirky adaptation of the Dahl story exhibits. The visual deception of magic, ironically, has been replaced by the tools of cinema over time. Bux’s — though cerebral in nature — could never be determined or denied. To his last day, he continued to perform, rejected by some for being a fraud, obsessed over by others for being the incarnation of a wildly obvious but improbable illusion. History still can’t fully condone or dismiss his methods but like most good stories with a pulsating self-willingness at its heart, it can’t keep him out either.

*Also spelt in some cases as ‘Khudah Bukhsh’.