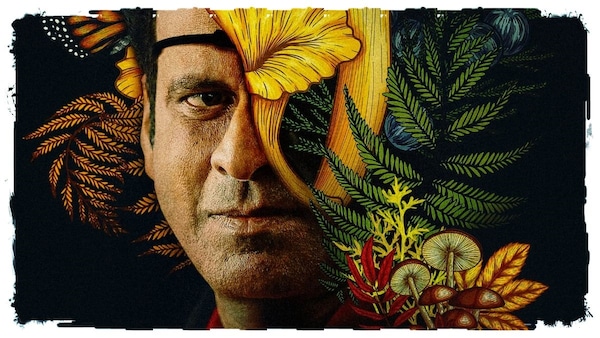

Killer Soup: A Whimsical, Vengeful Ride

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative over new Hindi films and shows.

Last Updated: 03.25 PM, Jan 11, 2024

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on January 11, 2023. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

ABHISHEK CHAUBEY’s Killer Soup, a sprawling eight-episode series, is one of the most inventive outings in the Hindi streaming landscape right now. This is saying something given how intricately and definitively filmmakers like Raj & DK have altered long-form storytelling. But even within the ambit of familiarity and expectation, Chaubey’s recent work is all kinds of whimsical. The director takes every flight of fancy and pushes the buttons of story and storytelling to arrive at a colour-popping black comedy that resembles a graphic novel in its dialled-up tonality.

The result is a largely gratifying series that unfolds straddling the thin line between playful and indulgent and, during its runtime, veers towards both. Chaubey’s Killer Soup is so unserious that the craft in designing it shines. It is the little details. Like a private detective (Bagavathi Perumal) clicking pictures in a tense moment with a camera that blinks low-battery; a man breaking into a dimly-lit house from a window, unaware that there is already an old woman inside watching television; an inter caste couple using the famous “Tu Hi Re” song from Mani Ratnam’s Bombay (1995), a film which centred on an interfaith couple, as the ringtone to score their tribulations. There are more instances: A man using a vase to protect himself but ending up holding only flowers before his attacker; a tough cop being introduced eating an ice cream; a blackmailer using an email address that goes: “mr_blackmailer@blackmail.com”.

Granted these come with the narrative style of black comedy but in the filmmaker’s hands they assimilate to create a strange sense of realism, stitching together an impression of life beyond manicured diktats. No moment unfurls in a premeditated tone. Witnessing them is almost like being privy to the process of creation while something is being created. For a show so literary (the main couple lives in Dickinson Lane, the main cop reads Robert Frost to motivate himself), watching it feels like observing the process of writing while something is being written.

These authentic embellishments prop up a plot so chaotic and excessive that it defies all rules of reality. In the fictional city of Mainjur, situated somewhere in South India and probably in Tamil Nadu, there lives a couple — Prabhakar Shetty aka Prabhu (Manoj Bajpayee) and his wife Swathi (Konkona SenSharma). Prabhu, a man with an inflated sense of self (a huge self-portrait hangs in his house), has few principles and even lesser integrity. His business, aptly called the “Last Resort”, is in the dumps and he has embezzled funds from “Rising Sun”, the flourishing enterprise of his elder brother and drug-baron Arvind Shetty (a terrific Sayaji Shinde). Prabhakar is bankrupt and Arvind is thriving. This hardly poses any difficulty to the former. He freely cheats on his wife and refers to her as babes. The endearing term loosely hangs on Prabhu’s mouth as if it is one breath away from being replaced with a cuss word, which it does.

On the other hand, the docile and obedient Swathi wants only one thing: to open a restaurant. But try as she might, she can hardly make a palatable soup. The nourishing dish might be beyond her but before being married to Prabhu, Swathi had a caregiving job as a nurse. Under the controlling roof of her household, she sneaks in stolen moments of defiance. Like wearing a burqa and learning how to cook against her husband’s wishes, and having an affair with a masseur called Umesh Pillai (also played by Bajpayee) who resembles her husband save for a squint in his eye. Umesh gives her words of affection and Pabhu gives her the false promise that once Arvind funds his dream hotel project Swathi will have her own restaurant.

This delicate balance of assurance and sham is disrupted when Prabhu catches Swathi and Umesh together. What follows is a physical altercation and Prabhu promptly dying of a heart attack. In the moment of crisis, Swathi, still holding on to her restaurant promise, takes charge and replaces Umesh with Prabhu. She slightly disfigures Umesh’s face (which he agrees to do as a show of love — his selflessness reminiscent of Vinil Mathew’s divisive 2021 film, Haseen Dillruba) and triggers a cat and mouse chase with more and more people dying and cops chasing multiple leads. A humble soup threatens to dismantle all.

Chaubey holds back little and weaves in the supernatural within the realm of the real, plotting ghosts and apparitions with ease. Multiplicity becomes the key. Across the eight episodes the plot moves in all directions possible, pushed and pulled by multiple characters. There is Arvind Shetty, his daughter Apeksha (Anula Navlekar) who wants to go to France to learn art. There is Arvind’s man Friday and former rebel, Lucas (Lal), from whose eyes nothing escapes. There is an accountant at Last Resort (essayed by Kani Kusruti) who Prabhu was having an affair with. There is a young, idealistic police officer, Thupalli (Anbu Thasan), who loses his life on the job. His sudden death gives a renewed sense of purpose to an ageing, lonely cop (a haunted and haunting Nassar) on the verge of retirement. There are several people and several things happening at once.

If the story becomes difficult to follow, the difficulty is by design. The experimental Killer Soup ensures a riveting ride and makes no promises about the destination. For a while it works out well. Chaubey’s keen eye for detail and the writing (Unaiza Merchant, Harshad Nalawade, Anant Tripathi and Chaubey are credited) make moments out of nothing. It only helps that the actors on display are all at the peak of their craft. There is only one thing better than a Bajpayee performance and that is Bajpayee performing (as a) drunk. As the timid Umesh, unwittingly drawn into the family mess and eager only to live with Swathi, the actor’s comic timing is pitch-perfect. There are scenes which are made infinitely funnier by his hand movements or the way he stresses on a word (he says ‘fuck all’ like it is both a compliment and an insult).

It is also a delight to see actors like Nassar and Sayaji Shinde, routinely stereotyped in Hindi films as the ‘bad guys’, being given meatier roles. Then there is Konkona SenSharma who can make lines sing by just mouthing them. As Swathi, who is ill-treated and overlooked by all the men in the family but determined to make her existence count, the actor is excellent. It is she who leads this tale of revenge with a singular want of being seen and treated better.

But any outing which relies on whimsy also runs the risk of running out of it. The tricks start to show and the laughs become less frequent. The madness becomes the method and ingenuity gets overshadowed by indulgence. Across its duration, Killer Soup tends to get lost in the maze of its own creation. After the fifth episode Chaubey becomes only more fanciful with the narrative (Nina Simone’s “Summerman” draws curtain on one) and the pace slackens. The threads tie up by the end, a little too late.

Thus, the one way of looking at Killer Soup is marvelling at the concoction of the journey the filmmaker has painstakingly crafted. The other way of looking at this story of control and revenge is to view it as a revisitation of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth. There are ghosts and witches, there are prophecies and the death of a young man that strengthens the resolve of his father (in this case a fatherly figure) to avenge his killing. And at its core, there is a struggle for power. But Chaubey adapts it by letting Lady Macbeth, a character prone to guilt and madness in the original text, take centrestage. It is Umesh, lower-caste and too attuned to being exploited, who is inflicted by fear. It is he who wants to elope with Swathi. But egged on belittlement and disrespect, she marches on undeterred to accomplish her dream of opening a restaurant and feeding people her soup by any means.

The most intriguing aspect of Killer Soup is the way Chaubey (who was an AD on Vishal Bharadwaj’s Maqbool, another adaptation of Macbeth) chooses to revisit the text. It is not as much the way he does it as the way he undoes it. He retells the play by puncturing holes in it. Much like its source, Killer Soup is stained by blood (people die all the time though no one is killed) but the way they are carried out speaks more of Chaubey’s intent to play with the text than stringently follow it. The series concludes as an anti-adaptation of Macbeth if there ever was one, with the filmmaker outlining the futility of fighting for power in this world, when it is a woman who’s doing the wrestling.

Premium

Premium