Hirokazu Kore-eda's Monster Examines How We Fail Those We Love

The Japanese master of mellow dramas stages an affecting inquest into the relativity of truth via overlapping perspectives.

Last Updated: 03.23 PM, Dec 19, 2023

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on December 19, 2023. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

Editor's note: Over the next few days, and as we count down to the new year, we'll be discussing some of 2023's best films and shows. Stay with us on this journey, to assess your end-of-year watchlist.

Previously | Anatomy Of A Fall: Justine Triet's Taut Courtroom Drama Summons Truth To The Witness Stand

IN a scene of grave desperation from Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Monster, two people sweep away the mud on a window so they can get a clear view of the inside, only for the view to be further muddied by the falling rain. The window has secrets to reveal, but won’t give them away so easily. Not until the mud of biases, hearsay and snap judgements is cleared away will the truth make itself known. Truth has never been more vulnerable to distortion than in the here and now. Facts are selected and tweaked as suits the selling of favourable narratives. Unfavourable ones are dismissed as “fake news.” With social media having created a free-for-all shitstorm of deliberate ploys to muddy the waters, Kore-eda cautions us against making judgements before seeing the full picture.

The Japanese master of mellow dramas stages an affecting inquest into the relativity of truth via overlapping perspectives: of widowed single mother Saori (Sakura Ando), of her son Minato (Soya Kurokawa), and of his schoolteacher Hori (Eita Nagayama). Such a framework may invite comparison to Rashomon. But Kore-eda does not use contradictory flashbacks of unreliable witnesses, as Akira Kurosawa did, to expose the fallibility of human memory. Each perspective does not contradict what came before, but recontextualises it. Each witness is unreliable less because of ulterior self-serving motives, more because of the limits of subjectivity. The same set of events when seen through different eyes, from different angles, help uncover clues and facts previously out of focus, turning our own reading of the story on its head.

As the truth gradually emerges, the power of this sublime drama of uncommon empathy builds incrementally and almost imperceptibly. Families — created by circumstance, broken by loss, challenged by upheaval — have always been at the centre of Kore-eda’s films. Through perspective gaps, Monster brings to focus how we often fail to understand those we love. At the same time, the film is also about how institutions fail children, how the pressure to conform can manifest as bigotry and bullying, and how a secret can take on a life of its own.

Monster opens with a high-rise building engulfed in flames and ends with a forest lashed by torrential storms. In between, the film depicts in succession the viewpoints of three witnesses to these clashes between nature and urbanisation. Saori works as a laundry worker and does the best she can to raise Minato after the death of her husband. For a boy who has lost his father, Minato seems like a happy enough kid. Until red flags become impossible to ignore: a lost shoe, a DIY haircut, and a late-night jaunt to a tunnel in the nearby wilderness, shortly before tossing himself out of a moving car. When Saori gets her son to confess as to what’s troubling him, he points in the direction of his new homeroom teacher Hori. Aggrieved and fuming, she storms into school to launch a campaign demanding the termination of the man allegedly mistreating her son, only to be met with scripted apologies and deflecting answers from the principal (Yuko Tanaka) and staff. Hiro, however, claims Minato is the bully himself. The victim instead is Yori (Hinata Hiiragi), a cheery, happy-go-lucky classmate who is teased as an “alien” by his peers and called a monster by his very own father. When Saori confronts Yori, he is quick to declare that Minato is not his bully, but his best friend.

The first two parts of the film play out almost like a mystery. As suspicious and cynical adults, we expect the worst. The last part takes the form of a tender story of a blossoming friendship. That the truth emerges only when we see the story through the eyes of Minato is Kore-eda’s way of suggesting that, contrary to conventional wisdom, adults have little understanding of the growing pains of adolescents. By playing with our expectations, Kore-eda challenges our presumptions and judgements — and how readily we make them. One of the more meaningful touches in the film is a musical sleight of hand. Stray brass sounds, we hear offscreen in the first two parts, turn out to be Minato playing the trombone in the third. Teaching him to play is the principal, who tells him to channel his pain and blow it all into the instrument. The scene about the power of music reads like a tribute to the film’s composer — the late Ryuichi Sakamoto, whose gentle piano chords resonate with hope, even if it is sometimes just out of reach.

As to who or what is the monster of the title, the answer is manifold: an abusive father who leads a sensitive child to believe he has the brain of a pig; a principal who can’t even look a mother in the eye when she seeks an explanation for her son’s sudden behavioural changes; a bureaucratic school system stonewalling parental concerns with fauxpologies in an act of self-preservation; a society keeping its cruelty hidden beneath the veneer of politeness; a culture which imposes such a dogmatic notion of masculinity it strains the close bond between two young boys, forcing one to fear his own desire and even contribute to the abuse of the other he desires just to save face. But maybe what is most monstrous of all is how the use of derogatory language (like “monster” and “alien”) can erode a child’s sense of self and lead to internalised phobias.

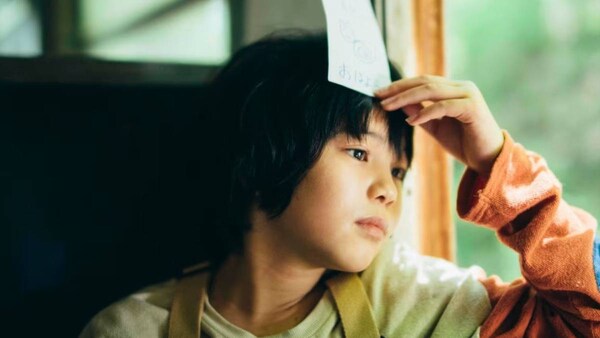

Minato and Yori are two boys on the brink of chrysalis, each of whose identity is at its most malleable. To get away from the name-calling and all the expectations of a constricting adult world, the two take refuge in a private fantasy world in an abandoned train carriage at the end of a dark tunnel in the forest. If Kore-eda is able to bring an unforced naturalism to these scenes of children coming to terms with their feelings without parental judgements and meddling, it’s because of his two young actors who broadcast the joys and pains of growing up with heartfelt sincerity, without hitting a single false note. The bond between the two forms the heart of the film and lends the poetry to its conclusion.

Monster won the Queer Palm and Best Screenplay at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival. The film had its India premiere at this year's MAMI Mumbai Film Festival as part of its World Cinema section.

Premium

Premium