Dharti Ke Lal: The 1946 Classic That Bared Horrors Of Bengal Famine

As we observe our 77th Independence Day, OTTplay revisits a classic of Indian cinema that fed the nationalist cause: KA Abbas' Dharti Ke Lal (1946).

Last Updated: 09.49 AM, Aug 15, 2023

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on August 15, 2023. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

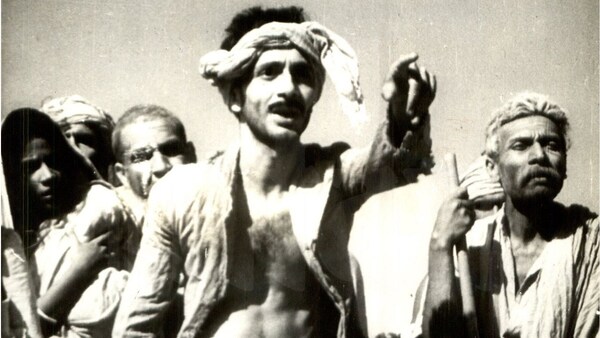

WHEN a farmer’s family is brought to the brink of starvation, they — along with thousands of others made destitute and displaced by the Bengal Famine of 1943 — move to the city of Calcutta in the hopes of being able to sustain themselves. This is the premise of Dharti Ke Lal, KA Abbas’ groundbreaking film from 1946.

The film was pioneering in more ways than one. Not only did it document and narrativise the horrors of the Famine, in which anywhere between 800,000 to 3.8 million people are estimated to have lost their lives, it was also the forerunner of the socio-realist movement in Indian cinema. How it came to be made deserves some exposition as well: over the World War II years, and as the Indian freedom struggle entered what would be its final phase, mainstream theatre had come to a halt. According to the Alkazi Theatre Archives, this prompted the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA; founded in 1942 and the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India) to promulgate a “people’s theatre”. Troupes associated with IPTA would tour the Indian subcontinent, bringing their productions (which denounced fascism and imperialism) to the masses.

Among these productions, ATA notes, was the one that proved to be IPTA’s most successful: Nabanna, or ‘New Harvest’. Written by Bijon Bhattacharya and directed by Sombhu Mitra, it depicted the plight of a family — one among many — caught in the throes of the Famine. Through this lens on a single family, a wider picture of the depredations of 1943-44 emerged: the rural-urban exodus, the havoc on a primarily agrarian society, the unfettered greed and corruption that made the sufferings worse.

At the time, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas had made his mark as a journalist (writing on politics and cinema for The Bombay Chronicle, from the mid-1930s to 1947. An interesting aside: also a writer for the same publication was Kusum Nair, a scribe whose role in the “last war of Independence” aka the Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 is well documented) while also handling publicity for Bombay Talkies. In the mid-1940s, he segued into screenwriting — he scripted Chetan Anand’s Palme d’Or winning film, Neecha Nagar, and V Shantaram’s Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani. And at the same time, he decided to venture into direction. The project was Dharti Ke Lal, an adaptation of Nabanna. Bijon Bhattacharya would collaborate with Abbas on the film, while IPTA produced the project. (Another play by Bhattacharya — Jabanbandi, and a Krishan Chander story titled ‘Annadata’, also informed Abbas’ vision for Dharti Ke Lal.)

In Dharti Ke Lal, we see the humdrum life of sharecropper Samaddar Pradhan and his family: his wife, two sons — Niranjan and Ramu, and Niranjan’s wife Binodini. These are intimate, everyday domestic scenes: the mother-in-law wishing for “good news” from Binodini, Pradhan sharing his concerns about the inadvertent delay in Ramu’s nuptials and other sundry occurrences with his dear friend and neighbour Ramzan, Niranjan going about his chores. Under the calm surface, tense eddies swirl. There’s a war going on in the world, the family must always keep an anxious eye on the weather, and there’s pressure on Pradhan to sell his stock of grain to a zamindar. Swayed by the thought of finally being able to host Ramu’s wedding with the pomp it merits, Pradhan hands over his rice to the grain dealer.

Even as a happy occasion comes about — Ramu is married to his bride, Radhika — Pradhan begins to feel the pinch of circumstances. Grain prices have spiralled. When food supplies run low, the zamindar, who bought the rice off Pradhan for 10 rupees, now offers to sell it back at 22. Ramu discovers that despite talk of a shortfall, the zamindar in question has actually been hoarding supplies.

Doom is impending, but Pradhan and his family squeeze in a few moments of felicity. Ramu and Radhika, in their newlywed flush, learn about each other. Radhika tries to navigate the prickly relationship with the women of her marital home: at least her mother-in-law is won over when her younger daughter-in-law becomes pregnant and then gives birth to a son. Binodini is wracked with jealousy but she too has a change of heart after torrential floods destroy the family’s holdings and she manages to protect her infant nephew from the aftermath.

The scene shifts from the family’s small joys to the worsening crisis. There is little to eat; the story is the same in most homes in the village. The zamindar returns, this time with an offer for Pradhan’s lands. Niranjan is staunchly against this, but hunger and deprivation cannot be staved off with belief alone. The family contemplates moving to Calcutta, where relief efforts mean they might at least have a bowl of khichdi a day.

We see Ramu’s hunt for work — and subsequent dependency on drink — unfolding alongside the general inhumane conditions in the city. Community kitchens are confronted with unending queues of the starving. Black marketeers capitalise on the desperation of the people. Once, driven mad with grief, Niranjan attempts to wrest a container of milk for his bawling nephew. Radhika is forced to turn to prostitution.

When an ailing Pradhan is about to pass away, he makes Niranjan promise that the family will return to the village and try once more to eke a living from the land. Although Binodini pleads with her to return with the family, Radhika stays behind in the city, hoping to be reunited with Ramu. Niranjan persuades Ramzan Chacha and the other villagers to try communal farming, so they can share the burdens and the rewards of their labour. Meanwhile, Ramu and Radhika are shown to begin an itinerant existence elsewhere, wistful for the home they lost but knowing that their ordeal will not let them assimilate back into the once-familiar milieu. The couple stands in for the millions who didn’t make their way home, who didn’t survive the crisis. Dharti Ke Lal ends with Radhika musing: “Our village, our country can never forget us. We are not the only two people who have died of hunger, got displaced, who sold their bodies, souls and humanity. There are twenty millions like us. Until our country gets freedom from slavery, from hunger, we will remain alive in our people’s memory, like burning flames.”

Dharti Ke Lal didn’t have a resounding commercial reception when it released in August of 1946, but it took on a life of its own in the years that followed. Its influence on early Indian cinema cannot be overstated. The cast — a mix of novices and theatre veterans, with names such as Balraj Sahni, Tripti Mitra, Zohra Sehgal — would have illustrious careers. (Sadly, Balraj’s wife Damayanti Sahni, who played Binodini opposite his Niranjan in Dharti Ke Lal, passed away in 1947.) And KA Abbas was on the cusp of filmmaking glory. Twenty-five years, several prestigious international and national awards, and an iconic partnership with Raj Kapoor later, he directed a film called Saat Hindustani — which marked the big screen debut of a promising young actor known as Amitabh Bachchan.

Premium

Premium