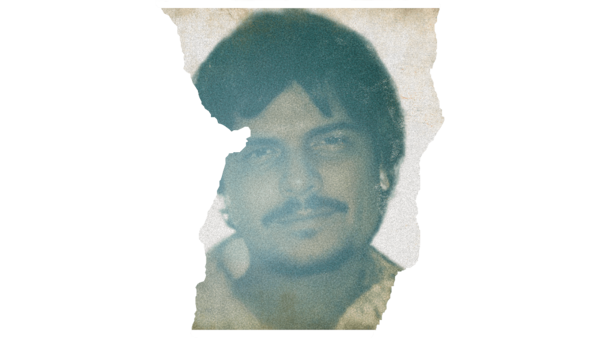

Amar Singh Chamkila: As He Was In Life, So In Death

As the Diljit Dosanjh biopic on the slain Punjabi musician releases, Manik Sharma delves beyond the oft-relived mythology, with those who have attempted to unravel the enigma of Amar Singh Chamkila

More than his ending and the sensationalism that prefaced it, it’s the missing parts of Chamkila’s life that present an emotional puzzle in the aftermath of his death.

Last Updated: 05.34 PM, Apr 09, 2024

This feature was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on April 9, 2024. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

ON 8 MARCH 1988, Amar Singh Chamkila sat down for a meal before leaving home for a scheduled performance he would never make it to alive. The dal he was served was strangely cold. The same day, his wife and co-performer Amarjot had received a pair of new ‘juttis’ to wear to the akhada. They did not fit but she decided to wear them anyway. Furthermore, Amarjot’s brother, who always drove the couple to their shows, never turned up that day.

“This is how authors of true crime titles write stories, I think,” muses Kabir Singh Chowdhry, the director of Mehsampur (2018), a docu-fiction film loosely based around Chamkila’s assassination. Much like artists who leave the world early in peculiarly violent or problematic ways, Chamkila has been rhapsodised as a phenomenon who ultimately unfolded as a tragedy. It’s the one trope you hope Imtiaz Ali’s upcoming film — Amar Singh Chamkila (out on Netflix, April 12) starring Diljit Dosanjh — will overcome.

Born and brought up in Punjab, Chowdhry spent a year researching the late Punjabi singer before sitting down to write the first draft of his script. Unlike the obsession with his death, Chamkila's music has rarely been afforded such a studious gaze. “I grew up listening to Chamkila’s songs, and I was most impressed by the rapport he shared with Amarjot. These performances were not just duets but theatrical exchanges. For everything naughty or provocative that Chamkila would sing, Amarjot had an equally curt response,” Chowdhry tells me. Often critiqued for obscenity, Chamkila sang about lust, women, love, drugs and everything under the Punjabi sun that irked (and perhaps even provoked) conservatives. Ironically, the bolder — and riskier — his music became, the more his popularity grew.

Rather than just season around the mythology of a dead artist, Chowdhry’s Mehsampur explores the voyeurism of post-death reflection. In his film, a drama-hungry director arrives in the town where Chamkila was killed, to forcefully excavate a wild narrative. There are repeated mentions of film crews and teams from Mumbai parachuting into town, hassling Chamkila’s collaborators for insights, and leaving without a trace. This sense of vulnerability is best embodied by Lal Chand, the dholak player and only living survivor of the crew that was assaulted in Mehsampur. Incredibly, Chowdhry managed to convince Chand to not only speak to him but also act, in a surreal recreation of a life that simultaneously feels like Chamkila’s remains.

What does a place only remembered for its dead become? What does a life, so valuably saved, but so irrefutably connected to death, take the shape of? Mehsampur explores these questions with startling, if at times discomforting metres of form and language. “I’ve always been interested in the contours surrounding the death, the survivors who live with a sense of guilt and the narratives that shape them from the outside,” Chowdhry says. In a scene from the film, Lal Chand drops his pants to show the scar of the bullet wound he sustained. Like any suspicious outsider, the protagonist of the film instantly undermines his wound. Almost as if the price of surviving must be backed by the earnestness of his grief.

Chamkila’s career was punctuated by prodigious fame, material success and at times, bluster. He rose and conquered but also poked and provoked. He operated at a time when violence had begun to take hold in Punjab. The Khalistaan movement had sowed fear into the hearts of the people... a fear that has taken its time to dissipate and unearth other blurry chunks of Chamkila’s life.

Baltej Sran, a school teacher and headmaster from the Ludhiana area, started interviewing people connected with the singer in 2011. “Back in the day, the only information we got was from the newspapers. And a lot of it was incorrect. Some claimed Chamkila was killed on stage, when we knew he didn’t even make it there,” he tells me, during a phone conversation. Sran shared a patch of land with Chamkila’s in-laws. Over and above that geographical connection, he was also enamoured by the performer’s luminosity. “If you heard him once, you couldn’t forget him,” he observes.

Over the years, Sran has developed an informal archive of interviews and anecdotes from Chamkila’s life. Much like the mythology that sustains as a self-feeding engine, Sran argues that recent movie adaptations of the singer’s life only scrape the surface of the man who was Chamkila. “He performed barefoot. He didn’t let any of his collaborators consume alcohol or meat before stepping onto the stage,” Sran says, countering the accusations of obscenity levelled against Chamkila. President of a memorial club, Sran commemorates the singer’s death anniversary every year. It is his way, he argues, of paying homage to a man who came from nothing but went on to become an icon. A man whose death has unfortunately become the map of his entire existence.

“There is more than just the one factor that accounts for his death,” observes Kabir Singh Chowdhry. “These things happen for a variety of reasons. Chamkila had received threats all his life, but he had also eaten into the business of his peers. He earned more, cut across territories, and had left his competitors behind.”

This territorial nature of a largely rural and informal industry can only be understood by experiencing the hyper-local design of art that is born and disseminated through the very soil it is produced on. Music and art have become studio-set isolative practices today, but back then they were frantic, nervy neighbourhood affairs, punctuated by performative glory and tangible woe. Chamkila is not the only Punjabi singer to have been gunned down by violent men. Many more, incredibly, have been killed for much less.

What does Chamkila’s life signify then? Well, for one thing it emblemises a violent chapter in the history of Punjab. So much so that according to the only recorded biography on the singer’s life written by Gulzar Singh Shonki, nobody from the Sikh clergy was initially willing to perform the singer’s last rites out of fear. The Ludhiana film industry, Sran claims, shuttered overnight. “The singers closed their offices. Changed their hoardings and names. Some left the city, and others fled the country,” he recounts. For almost a decade after Chamkila’s death, there was an unacknowledged omertà in the Punjabi music scene, ultimately broken by emerging talents from the more urban pockets of the state. “But that lull ate (up) the akhadas. That time can never come back. The world has moved on,” Sran rues.

More than his ending and the sensationalism that prefaced it, it’s the missing parts of Chamkila’s life that present an emotional puzzle in the aftermath of his death. Especially for the ways in which his life mirrored a state’s interaction, over time, with violent socio-political upheaval. Then there is the recurrent horror of having lived through it, as embodied by Lal Chand — a ghost of the thriving memory of the singer who was Chamkila.

Premium

Premium