Ae Watan Mere Watan: Unwatchable In All The Ways You Can Imagine & Some That You Can't

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative over new Hindi films and shows

Last Updated: 03.51 PM, Mar 21, 2024

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on March 21, 2024. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

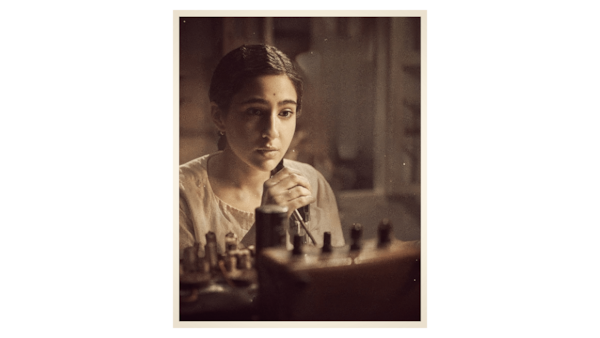

WITH the recent spate of nationalistic Hindi films, the most obvious pitfall has been the increasing jingoistic overtones of such narratives. For the discerning viewer, the task is now to locate the seeds of propaganda planted in the soil of storytelling. One would assume Kannan Iyer’s Ae Watan Mere Watan, a film centred on the life of freedom fighter Usha Mehta, to highlight this shortcoming — if not critique it. But the film throws a steeper dare to the audience, one that tests the limits of their patience and bandwidth of their attention. Ae Watan Mere Watan challenges one to sit through it.

This is neither an exaggeration nor a sly remark. If anything, it is an approximation of the experience of watching Iyer’s film that, at several points, feels like enduring a survival sport. The outing is so dull in intent and so lacklustre in execution that I was convinced (till the end credits proved otherwise) that the makers had erroneously shown us the first draft, the rehearsal footage if you will, and a lot of work still needed to be done. The most pressing task being to scrap whatever was already shot.

Ae Watan Mere Watan might go down as one of the most forgettable Hindi films this year but there is something to be said about the way it goes about doing that. There is a stunning callousness in the way scenes are staged, a sponge-like superficiality to the characters where they soak up the directives and then spring back into shape like they have absorbed nothing. The film feels and looks like a school-level skit and there is a flippancy to the narrative that only grows through the runtime.

This lack of voice, conviction and direction (Iyer had previously directed the 2013 film, Ek Thi Daayan) feels like an artform in itself because the source material is damage-proof. The film is based on Usha Mehta, a Gandhian and freedom fighter whose contribution to India’s struggle for independence is immense. Born in Gujarat, Mehta and some of her friends had started a covert radio station in 1942 called the Secret Congress Radio, that broadcast messages from Indian leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and infused patriotic fervour among the people against the British during the final years of colonialism. She was 22 at that time.

This occurred in 1942, around the same time when World War II was raging and the Quit India Movement had the nation in its thrall. Both contributed to the politically tense climate in the country. Radios were banned and all resistance was cruelly suppressed.

It is a fascinating story not just because there is little about Mehta and her life that is talked about. But also because she falls into that league of freedom fighters who aided in birthing a new nation and felt disillusioned with what happened post that. In his reimagination, Iyer does nothing right. What could have excelled as a retrospective story (an older Usha Mehta looking at the past while living in the present of her unmaking) is designed as a heedlessly rousing heroic tale where the British police officers talk as though their lines are written by Chat GPT, look like they are in a fancy dress competition (one of them even dons a leather jacket and gloves while on his nocturnal hunt for the radio station), and the Indian freedom fighters pose personal questions to Gandhi as if the latter is some godman out on bail.

It is partly ridiculous and wholly unbelievable how progressively unwatchable Ae Watan Mere Watan becomes. All the characters look like they are from South Bombay and are wearing white clothes for fun (Abhay Verma’s portrayal of Usha Mehta’s friend is woeful. The actor looks like he was auditioning for The Archies at the same time). Emraan Hashmi as Ram Manohar Lohia, the freedom fighter and supporter of Congress Radio, gets nothing to work with. The most character depth he is lent is spinning the khadi wheel whenever he gets the time. Sparsh Shrivastav, last seen in the excellent Laapataa Ladies (2024) feels short changed as a polio-affected colleague of Mehta.

Then there is Sara Ali Khan as the titular character. This is her second release in the space of a week (Murder Mubarak dropped on Netflix on March 15) and it is worrying that both outings tried to prop her up and she failed them both. Unlike her contemporaries (say Janhvi Kapoor), Khan’s choices have been more conventional. She leans more towards the mainstream which is not the problem here. The problem is she leans on playing them the way she has seen actors do that in the past. For instance, her turn is reminiscent of ‘90s actresses (particularly Karisma Kapoor) in a way that feels both jaded and misplaced. As Usha Mehta, Khan is almost robotic in her ways. Her eyes get bigger when she is shocked, her chin turns up when she is hurt. Not only is she ill-equipped to shoulder such a role but her ineffectual depiction makes it impossible to discern if she was saddled with bad writing or if she ruined the written word.

Watching nationalistic films today has become an exercise in suspicion. Resultantly, if unfairly, I was hyperware at the prospect of Ae Watan Mere Watan. But the film builds up to such chaos of clumsiness that its politics becomes a footnote. Here’s an example: at one point, a rich girl compares her lack of agency with a man who cannot walk properly. It gets wilder by the minute till it culminates into a riot like scene which I am assuming was funded with the money that the makers saved by shooting most of the film on a subpar set. My only concern then was to sit through Ae Watan Mere Watan with my brain cells intact; whether that was in fact achieved is something I am not sure of anymore.

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of OTTplay. The author is solely responsible for any claims arising out of the content of this column.

Premium

Premium