Mari Selvaraj On Vaazhai & His Other Works: Will Continue Making Films That Trigger Some Change

Selvaraj spoke about bringing his life story to the big screen, the scars of childhood, how art has healed him, and how some remnants from his past continue to haunt him.

Last Updated: 04.33 PM, Aug 31, 2024

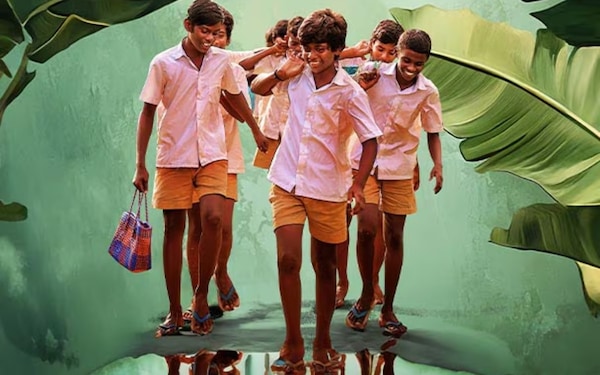

MARI SELVARAJ's Vaazhai (banana) is the kind of film that plays repeatedly in your mind, days after you watch it the first time. It is a film that needs time to seep into your soul, and trigger feelings a first-time watch might necessarily not. And that seems just right for a film that has at its core a single-line idea — the life of a boy who wants to study but has to go to the banana grove to pluck and carry fruit. The real effect happens much later after the end credits roll, and when you get back to your regular life. Your privilege hits you in the gut, and the sight of a smooth yellow or green banana triggers emotions you’ve never felt before. This, then, is Mari’s signature — making films that are accessible and non-intimidating, but films that work on your thought process and cultural beliefs, nudging you towards change, and a shared ideal.

In a long-winded interview after the film’s release, Mari spoke about bringing his life story to the big screen, the scars of childhood, how art has healed him, and how some remnants from his past continue to haunt him.

Edited excerpts:

In the recently-premiered docuseries Angry Young Men, writer-poet Javed Akhtar’s voice cracked as he spoke of how he’s never forgotten the hunger and hurt he experienced as a young man…

That’s true. You never really get over that. I have not yet forgotten where I came from. All those who carried bunches of bananas with me are still doing the same thing. When I go home, it disturbs me. They wear the same clothes and live the same life. The only change is that they have better vehicle comfort. They go to work, knowing the same incident that scarred me could happen to them. Even today, when I see a crowded banana grove or a crowded lorry, the past comes back. It’s never really left me.

I used to go to work with my mother, and even today, when I see a mother and child go to work together, it disturbs me. And, this happens often. Even in the shooting spot, if I see a child acting and the mother waiting, I will be unable to sleep that night. The fact that kids have to work disturbs me a lot.

With cinema, at least I know that when kids work, it will take them to the next stage, it will give them recognition. They will be safe on set and their work will be showcased outside.

You speak a lot about hard work. How do you view work?

I get very angry with hard work that only puts food on the table, keeps you in the same space, and does not give you respect or security. Everyone works hard, but some people’s work takes them forward. I am afraid for all those who don’t have that privilege. Their work gives enough to just survive, and that’s unfair. Their work renders them invisible.

Speaking about just this, your films have always thrown light on invisible hard work, processes and people. Vaazhai does that very effectively, but did you expect this kind of reception?

I intended to draw people’s attention, disturb them and make them watch the story of an innocent boy whose work is being absorbed by society and who yearns to study. What is his mistake, but that he is born to his parents, and in this society? If you look at it, we are linked to his life too. He believes this is his lot, but I wanted to show that his life can be different. I ran away from that life. If I had stayed, I would have continued to live that life.

I wanted to convey that it is unacceptable that one person’s work leads to his development, while another person’s work keeps him in the same place. What is the expectation of the downtrodden, what is their hope? They are restricted to a life of adhigapatcha uzhaippu, kuraindhapatcha aasai (maximum hard work, bare minimum desire), and in this case that desire is to just study. This innocent desire is the reason why many societies have grown. Why is it so difficult to provide the bare minimum?

In the movie, a broker thinks much before giving them one extra rupee. He thinks that is a big deal. He reduces the value of the employees’ hard work and does not let them see its worth too.

If the audience introspects on these points, I am satisfied.

Why is it important to tell these stories of the oppressed with empathy?

A downtrodden person struggles to share. He thinks he is all alone. When you make such movies, they will get the faith that at some level, everyone’s life is the same. That we are not alone.

The imagery and metaphors in your works are imbued with meaning. A recurring motif is the human-animal bond. Be it Karuppi the dog, the piglets or the rail poochi of Vaazhai. Thoughts on that?

My characters are usually very innocent and they are drawn to similar creatures. These happen to be animals, insects and worms. Like my characters are dependent on others, these creatures tap into the characters' innocence. That only elevates my love for human characters. Every creature, big and small, is intrinsically linked, and everyone in that chain must get their value. Animals give love back so easily. Theirs is an easy friendship without expectations.

Do you still harbour previous hurt and bitterness? Or have you learnt to use that to climb the ladder of art?

Bitterness does nothing to me. I grew up and flourished amid that bitterness. So when detractors try to be bitter with me, it does not hurt me. I’ve seen all this before reaching where I am today. I feel bad that someone wants to hurt me, or my movies. I then think that I have to work for him too, to draw him towards my creations, to make him understand. So, the challenge gets bigger.

Mari, your films are subtle teachers too. In Vaazhai, the Communist movement is an important layer…Among the more evocative scenes is the Communist flag resting on a bed of 'marudhaani' (henna) leaves…

We all saw things in our childhood that caught our attention, but they were not very clear to us. But, you instinctively know that they come from a good place and that they will fight for you. The Communist movement in Vaazhai is that. Sivananidhan (Ponvel M) loves the flag because it is a precious possession of his father. He connects it to him. He also thinks Kani (Kalaiyarasan) will speak for his people and hence gifts him the flag. The hope the underprivileged have is that this symbol can be trusted.

I hope the audience feels that way too. I hope the Communists who watch the film realise how much affection the working class has for them. That hope they have is such a big thing, it does not come easily.

How has the feedback on the film been, Mari?

Ah, that’s something I am still in two minds about. I have taken my time to speak about the film, post-release. The feedback has been incredibly moving. I did not expect it, but I can see the film turning into a wave. People usually own success, magnificence and pride, but here they have owned my pain. They’ve made it theirs. What a moment that is! Some people call my number and once I answer, they choke and are unable to speak. So now, I tell them they’re speaking to my manager and then continue the conversation myself. It has turned many people emotional. I am not sure how to understand or decipher this reaction.

I am the film's producer too, and this reaction has made me forget the commercial side of the film. I am not actively looking at the numbers and whether it has made money. The emotions people have gifted me for Vaazhai have made me forget everything else. I am utterly grateful for that.

Mari, you’ve maintained art is an instrument of change and a healer. How exactly did it heal you?

I’ll go back to something I said earlier. Art told me I was not alone. From being in a position where there was no one to listen to me, I’ve come far. Art turned my experience into something valuable. It brought me to a place where it can heal any wound, and solve anything.

Art helps me sit in one place and touch the heart of someone sitting thousands of miles away. It has given me the faith to trust myself.

Do you see yourself making films that fall in a happy space?

Ah, I don’t go by genres at all. I only go by how honest my four films so far have been. My art has created the space for people to speak of their experiences, and that makes me very happy. People seem to believe I will only tell good stories, I should not let them down. My only hope is that no one should take back anything bad from my films. That they should exit the theatres on a good note.

This being the case, how did you react to the Maamannan caste supremacy issue, where people from a dominant committee tweaked scenes from your film to share caste pride?

I did not feel bad. I make a movie knowing every kind of person will watch it. I know they exist too, but why should I react to someone who is so jobless and irrelevant he spends so much time pushing forth an unnecessary ideology, using the creation of someone who is the antithesis of them? I have created a storm in the minds of these people. And, that’s okay. Vaazhai is my answer to them, and they are silent now.

When you celebrate an important character with ‘unnecessary’ traits in my films just to irritate me, you need a reality check. But, whatever happens, if your intent is right, you should not be worried about such misunderstandings.

No two people will understand cinema the same way. I will continue making films that trigger some change. I will keep working. To them, I say: You and me, this game did not start today. It won’t end soon. I will keep working and one day, you’ll understand too.

How easy is it for someone like Mari to work in Tamil cinema now? Are you in a space where you have the freedom to make what you want?

Yes, I am in a very comfortable place now. All my producers have trusted me, and I am working with them again — Dhanu Sir, Neelam Productions, Red Giant Movies etc. My actors would love to work with me again. My filmmaker friends helped me during Vaazhai. They wanted it to do well. I have to ignore the negativity and keep working at a faster pace, that’s all.

You’ve achieved something wonderful in this film with child actors Ponvel and Rahul (who plays Sekar, Sivanaindhan’s friend). How is it working with children?

I loved it. I feel all directors should work on at least one children’s film. If you need to restore faith in yourself, if you need to love yourself as a director, and re-develop unshakeable faith in your abilities, work with children. They are the next generation, and a conversation with them is precious. You create interesting work with them. You make them understand. I felt like I was making my first film. There’s a different energy on set when kids are around. I now also understand why some directors keep making children’s films. It’s almost an intoxication.

Your film language, visuals, imagery and signature are the result of years of work that went in silently, unseen by the world. How did you feed this desire to learn?

Reading. I had a lot of self-pity that I was alone in my suffering and that no one else was in the same position. Reading world literature as an assistant to Ram Sir changed my worldview. I knew that while the innocents world over might speak different languages, they are united by one language — that of lived experience.

I’ve never been to Russia, but Russian literature brought that country alive for me. I imagined a visual. I discovered new layers in my personality that were visible only to me. That changed my filmmaking.

A book that particularly affected me was Chidambarasmarana by Balachandran Chullikkad. I read the Tamil translation and I was stumped to read about the mistakes a person has committed and how they helped him understand life better. That book changed my writing style. Whatever I held back, I began to share.

What does the banana mean to you today?

In the village, I used to carry the kadhali or yelakki variety on my head. When I moved to Chennai, I would buy four or five fruits just because I could, and eat them with full gethu (style). That said, even today if anyone does not handle a bunch of hanging bananas properly, I get angry. It is so fragile, and people tend to twist it and tear off a fruit without much thought of how it landed there!

But, I do not react badly when I see bananas wrapped in cling film in a supermarket. That does not feel like “my” fruit.

Subscribe to our newsletter for top content, delivered fast.