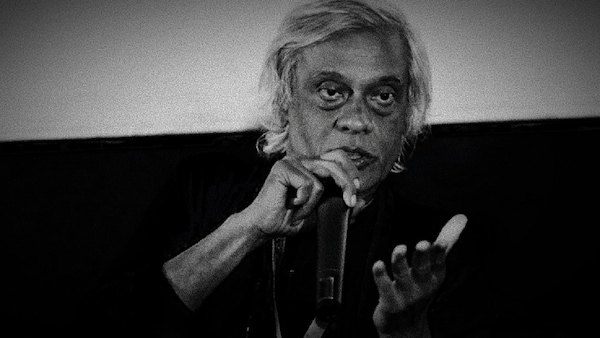

The Sudhir Mishra Interview | 'We All Peddle Lies'

In a conversation with Subha J Rao, filmmaker Sudhir Mishra dissects the anatomy of Afwaah, his most recent film; the long lives of rumours; and what it means to make cinema with a conscience.

Mishra says in Afwaah, 'a rumour can be a metaphor for anything'.

Last Updated: 12.06 PM, Jun 04, 2023

WE live in an age of misinformation and fake news. Inexpensive data has ensured rumours fly thick and fast, sometimes harmlessly, sometimes with vicious effect and human toll. Of late, in a deeply-polarised state, #LoveJihad and #Beef are two hashtags that get the rumour mills working on overdrive.

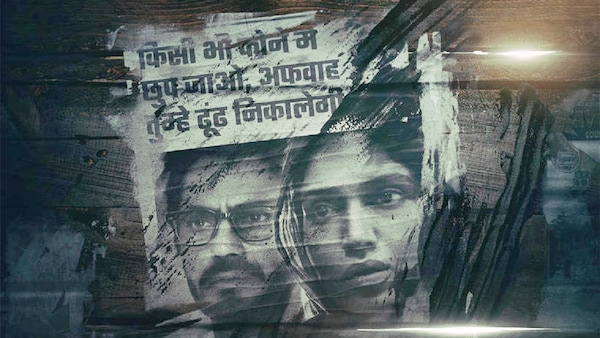

What happens when a politician’s daughter and an advertising professional end up having to run from political goons, and the bloodthirsty chase is fuelled by these two hashtags?

Sudhir Mishra’s Afwaah (Rumour) is an incisive film that cuts to the chase and is set in the Rajasthani hinterland where caste pride and misogyny rule. Nivi (a lovely Bhumi Pednekar) might be educated and the daughter of a powerful politician, but she’s still just a woman who can be pledged to a suitable suitor. She’s not above using her influence too. Advertising professional Rahab (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) can sound worldly-wise and self-aware, but all that crumbles under pressure. Young politician Vicky Bana (a searing Sumeet Vyas) looks sophisticated, but can do anything to score a political point, even order the killing of an associate, if it might help him. Everyone has shades of white and grey and even black, a victim or owner of their circumstances.

Over the years, Mishra has written and made innumerable films — Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron, Yeh Woh Manzil To Nahin, Iss Raat Ki Subah Nahin, Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi and Yeh Saali Zindagi, among others — that marry politics and the dark underbelly of society, films that speak of lofty ideals and films that aspire for home — almost all of them deal sensitively with the human condition. In an interview, Mishra speaks about staying contemporary with his creations and how each one of them has stood the test of time. Edited excerpts:

What was the first rumour you remember hearing?

At home. That my step-grandmother was a witch. Soon, I realised this was untrue. In reality, she was a pretty erudite person!

What was the trigger for this film?

The world around us. If you open your eyes, it’s all around you. The problem with a rumour is that once it is out, it is impossible to control it or deny it. It’s already reached everywhere, and that was the idea of the film. Also, the realisation that we all peddle lies — minor lies, maybe, but lies of convenience. Rahab lies about his journey of self-realisation. Ultimately, he just wants to not die.

Your earlier films seemed relevant and contemporary when they were released, and continue to remain so, decades after they were made. How does that happen?

Well, I think that’s because though time has passed, the essential human condition has not changed. For instance, Afwaah can be a metaphor for anything — a rumour follows and attempts to destroy a woman, and women are most vulnerable to rumours. I think my films lead you to questions rather than answers. They nudge you to find your answer.

You recently tweeted about how liberals were not backing films such as yours in theatres. And went on to have a conversation with Vivek Agnihotri, who has been making films that get weaponised to foment hate…

I think we should not stop having conversations. Part of what the right wing bases its fight on are rumours and half-truths. We have not addressed those half-truths.

Yes, we must all feel for the plight of Kashmiri Pandits, but Vivek used it for something else. Even during our conversation, I asked him why he was filled with hate and why he can’t allow others an opinion about his films. It helps that I know him from before. He’s not parachuted from somewhere else. You don’t have to agree with what the other person is saying, but you must converse.

Even in Afwaah, even after Nivi disowns her father, she sits down to have a conversation. We don’t have to always walk away. There is a meeting point. Sometimes, you can listen to your worst enemy and learn something about yourself.

How did you write someone like Nivi, who is smart and educated, but still a victim of her circumstances?

You see many Nivis. She’s like the many women who are exposed to everything today, but are also restricted by their environment. Someone has already written the screenplay of their lives. She has her flaws and she’s not above using her family name, but she also knows to give back when misogyny and patriarchy raise their ugly head.

Sexism is another thing the film speaks about.

Yes. Everyone seems caught in it. The female cop is among the few who gets out of it. While getting them out, she saves Nivi and another pregnant girl. That’s her own victory too.

In all this social commentary, you seem to have a ring-side view of issues.

It’s because of the accident of my birth, and where I was born. The sheer variety of experiences I’ve had as a child and adult, what I’ve observed and absorbed, come through in my films. …

Have you seen lives destroyed due to rumours?

Yes, it can happen to anyone, anytime. I’ve seen it happen far too many times.

How do you cast for your films? Sumeet Vyas seems a very interesting choice for someone without a conscience…

Yes, he’s an interesting casting choice. I like to cast against the grain. He’s a very good actor and I wanted him to be a villain, but not in the conventional sense. Plus, he’s from Rajasthan, where the film is set.

Sharib Hashmi was good as Chandan; Bhumi worked so hard to become Nivi. She’s someone with a certain intelligence and opinion and is well-read. I had a great cast that came on board without reservations.

At a time when anything said against the government makes a creator ‘anti-national’, how did you have the courage to make a film about two of the most infamous hashtags?

Well, I’m happy I made it. More than 95 percent of people who watched it have loved the film. The press has been very kind. I hope this film is an intervention, and I am glad it was not silenced. I think this film will give hope to younger filmmakers that you can make and speak your mind in movies.

Subscribe to our newsletter for top content, delivered fast.