The Selvamani Selvaraj Interview | 'Veerappan's Story Is One That Teaches Us To Be Better As A Society'

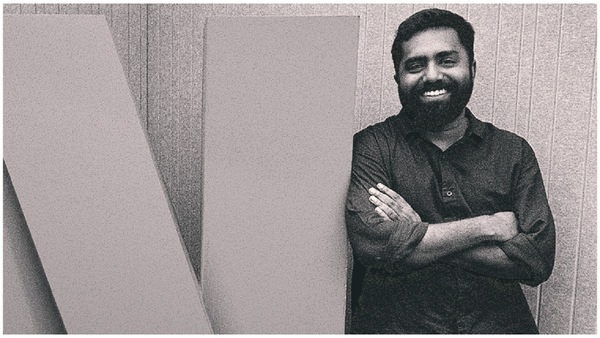

Selvamani Selvaraj, director of the critically acclaimed Netflix documentary, The Hunt For Veerappan, speaks with Subha J Rao about its making.

Last Updated: 01.41 PM, Sep 03, 2023

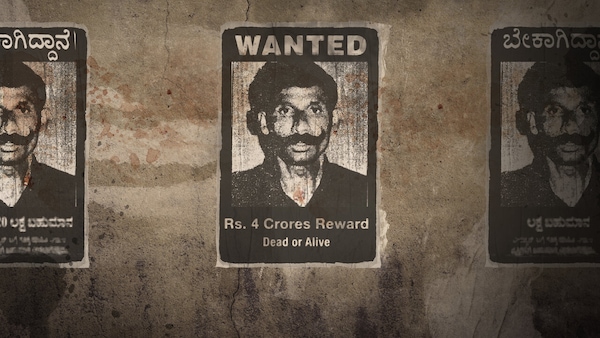

THE early 2000s. A Chennai school. Two things fascinated the children — director Naga’s Vidaadha Karuppu, a television series about superstitions and the supernatural, and brigand Veerappan, who was still in the news for his exploits in the forests of Tamil Nadu and Kerala. He’d killed more than a thousand elephants for their tusks, and numerous officials who tried to nab him.

Selvamani Selvaraj was in Class 9 or 10 in DAV Mogappair, Chennai. It was an impressionable age. A year earlier, he’d heard of the kidnapping of Kannada superstar Rajkumar. These things registered but they were far away, geographically. His only exposure to the hinterland was the yearly summer vacations in his hometown of Thiruvannamalai, a land that charmed him. And then, during a family trip from Chennai, their vehicle was stopped near Sathyamangalam, and they were told to take a two-hour detour, because Veerappan and his associates were supposed to be in the jungles nearby. Suddenly, Veerappan was not a distant figure.

“I remember asking many questions as to why we were told to take a longer route. I did not understand why the elders were afraid. I just kept going back to a routine headline those days — that if Veerappan was not allowed to surrender, he would kill those in his custody. At that age, I saw it as a desperate move by someone who wanted to get back into society,” says Selvamani.

That same boy, after an engineering degree in BITS Pilani and an award-winning movie Nila (now on Netflix), would, in his 30s, go on to direct the critically acclaimed documentary The Hunt for Veerappan, streaming on Netflix. The documentary examines the beginning of the Veerappan saga, his reign of terror, and death in 2004, speaking to all stakeholders — villagers, his wife Muthulakshmi, forest and police officials. It stays non-judgemental, allowing space for different perspectives.

The 34-year-old filmmaker has moved on to his next project, Kanta, starring Dulquer Salmaan, and in a conversation spanning an hour-and-a-half, Selvamani spoke with this writer about his introduction to documentaries, the importance he attaches to establishing a bond of trust with his subjects, being neutral as far as possible, and how his goal is to add to the perspective about a topic or issue. Edited excerpts.

Veerappan as a character was something you’ve grown up with. What was the immediate trigger for the series?

I think the story always fascinated me as he was alive and things kept happening till 2004. A recent trigger was two books I read — Chasing the Brigand by K Vijay Kumar, and Solagarthotti by Pa Balamurugan. Both were riveting, both were polarising. And so I wanted to find out for myself as to what really happened.

Your documentary is riveting but also has a certain academic appeal and is almost educative. What has your exposure to documentaries been like?

I was exposed to documentaries in college and in the initial years of working. I had an entrepreneurial spirit and wanted to start something on my own, instead of working with a multinational.

I still remember some creations I watched — The Fog of War (about former US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s observations on the nature of modern warfare), Fahrenheit 9/11 (about the Iraq war and the role of media) and Zeitgeist: The Movie (about mythology and belief). They made me see life differently, I realised that there is something apart from the mainstream narrative. That documentaries can be investigative and broaden perspectives.

Somewhere I knew I was going to be a feature filmmaker. Nila played in fests before going to OTT and after reading the Veerappan books, I wanted to come up with a fictional feature. Chasing the Brigand was cinematic and there was a lot of drama in the struggle to stay alive every day, flirting between life and death. I thought I could fictionalise it, and pitched it to Netflix, but they were more interested in a documentary. Commissioning editor Aloke Devichand charmed me into making this. He just felt that I could do it, because of my intent. And, I went for it, thinking ‘Why not?’

What was the research process like? Your subjects seem to share an easy comfort with your presence and speak their minds. Their body language shows they felt safe speaking to you…

I hit the ground, meeting people. I realised early on that this was not my story to tell. Those involved with it had to. The survivors showed so much strength, it had to be their voice. I learnt the process of interviewing, of letting people speak, of listening. I did this for six months, and developed tremendous respect for the people, marvelled at their lives, at their resilience. What every single person there had faced. It was almost a year after the first meeting that I put a camera in front of them.

I did not probe them too much. It took that time for them to understand me, and me them. I was led by curiosity, and the intense research was born out of fascination for the subject. I realised we were on to something special and I wanted to be thorough. It was a very relevant and important story to be examined and the people involved had to speak about the things bothering them, they needed to not sense the camera. And, I think we were successful, at no point were they intimidated by the camera.

But, it was not easy. The first two months, they did not want me anywhere near them. Then, they’d reveal small nuggets. I would let them speak, and then, they were ready to tell their story. We built bonds with them, sometimes the researchers did, sometimes I did that from scratch. We were interested in them as people, and I think they got that.

Our intent was to understand Veerappan better. And, we went with what people said. Rarely do we steer the conversation to get them to say something we wanted to hear. It was all open ended.

It helped that the entire team had a lot of fascination for the story we set out to tell. For, no one can tell with certainty that this is how the end was. One person whose quote I did not eventually use, told me that only two people know what really happened. And that’s why it is a secret.

At any stage, were you worried you’d let down the people’s trust, because of which they agreed to speak in the first place?

It is a very tricky space to be in. They come to you because of the trust, and my first prerogative while piecing this together was that the representation has to be accurate.

This is the responsibility of any non-fiction filmmaker, the burden we carry. I struggled till the very end, wondering if I did what I set out to do. We had a lot of arguments if we stuck to the intent we began with. That said, I cannot every call myself fully successful as a documentary filmmaker.

There are things you leave out for brevity, there are interviews you don’t use, there are conversations that are trimmed, which would have otherwise lent a person that much more character. You saw their audaciousness on screen, not their tenderness. But we were there to serve just one purpose : try and understand the man, even if it meant holding on to every single small thing or event anyone recalled. Each of those helped us understand the man better.

Were there times when you had to prevent yourself from reacting as an individual when you were being told things that were very brutal?

I tried my best to be as de-sensitive [sic] as possible during the interviews. Each time you understand something about human emotions, and it is not fair to react to it. What I was trying to understand from Muthulakshmi was if she was caught in this situation or did she understand and get into it. Was she just an observer or an active participant? She comes from a stand of being there for her husband. She knows she can’t reason with him, and she loves him, and she gives a rationale for why he kills.

She was playing two roles — she was a proxy for him, telling things that are verbatim, and she revealed her journey from that of a 15-year-old to a woman of 30. I have the deepest respect for the survivors. My ego took a beating, and I set out to understand who she was. I might not find the result palatable, but that’s her life. I found that process of going in with an idea and discovering something else altogether very beautiful.

At every stage, I was only trying to make the audience feel what I was feeling, without employing any technique.

For instance, when it came to instances of violence, somewhere it was clear they would go for the deconstruction of the violence, they gave me something I could not even fathom. I cannot be a participant in their previous journeys. Some of them appear to lack sensitivity, but that’s only because they are expressing what happened in the only way they know.

One thing I guarded against is sensationalising anything. And so, a lot of material that would have made the documentary wilder, bigger, got left out. What these people gave me was a human touch to the face of violence. They have harsh feelings towards the abuse of power, and that’s their life. Why should I be a reductionist and dismiss something I can learn from? And so, I tried my best to keep my personal feelings away, and just listen when they said things I could not fathom.

If I had not adopted this style, and had decided to analyse those conversations, the documentary might not have been as empathetic and non-judgemental. I let them speak, and listened with respect and patience. I translated my experience for the audience.

How was it to walk in the forests that were once considered impenetrable?

It was surreal. I felt something deep walking into the forest to meet people. Most were able to speak to me after everyone else at home slept, and it was extremely dramatic. This was their natural environment and I realised that if they narrated their story there, it almost felt like they were sharing a secret.

Each of the people who feature in the documentary has a specific frame you identify them with. How did you decide the lighting, the framing, and how you wanted them to appear?

I tried to go with their character and how they appeared to me. Unlike in a movie, where each person can be dreamed in different ways, here, the framing was also an identification mark, to say this is so and so. For example, for forest officer BK Singh, the frame was kind and vivacious, because he’s that kind of person. It was a reflection of his personality.

When framing police officer Navas, the team decided to get him to speak in the forest, because he spent 12 years in the jungle, preferring combing the jungle to staying in the police station. I wanted one person from either side in the forest — I finally decided on Navas and Anbu, who knew the forest intimately.

Police officer Senthamarai Kannan gets a night setting, because he drew all his plans in the dark. He was the one who decided they could never capture Veerappan in the jungle.

I knew the documentary had to piece together the experiences of many people. For example, I had to choose one person to speak of Karnataka’s 10-year account of the hunt, among say 300-400 officers. I went for the one person willing to talk about things that might make others uncomfortable. Because he had a conscience, and I could appeal to it.

If someone were going for glory, then the frame would be different. My DoP Udit Khurana and I decided we needed to give one defining frame for the 25 characters who appear in the documentary, because I don’t like putting names against faces repeatedly. Aesthetically, I like it when the frame becomes their personality and calling card.

Among mediapersons, you chose Sunaad to speak about the hunt. Why did you decide on him?

I liked Sunaad’s take on the story. He had the same fascination for the subject, and he was following it when the story was live. He was invested in the twists and turns of the story. I liked his perspective in the mix, because he had no skin in the game. He was objective, and while I might have disagreed with some of his opinions, I needed it in some places. Sunaad is not my direct voice, but I liked it when he spoke with that fascination, backed by details that he remembered like the back of his hand. Even a police officer might have forgotten the number of holes they dug in Palar, but not Sunaad.

(There’s also photojournalist Sivasubramaniam, whose photo of Veerappan replaced the grainy black and white version everyone used till then. He speaks of how he knew that he would land something special if he managed a photograph of Veerappan).

Has your perception of Veerappan changed after working on the documentary?

We all know he was this larger-than-life criminal. From the stories I hear, he seemed to be a normal guy with anger issues. It is said that before anyone takes up arms, they need a sagacity of thought and an ideology. The majority of people see him as a cold-blooded murderer. I managed to get good access to those who were close to him, and I felt their perspective should be registered too.

Veerappan’s brutality towards elephants was well-known. He had a strong sense of right and wrong. He would dig in and do something even if he felt it was wrong. I tried hard to find out if he had a shred of remorse, I wondered how can someone do all this and be self righteous, and cite examples from the myths to justify his actions. He resisted authority with brutality.

In fact, Navas and many of the forest officials said they would never forgive him for killing over a thousand elephants, an animal considered godly by the villagers. He killed with callousness, be it animals or people.

Did it leave me sick? Knowing I was sitting in the presence of people who took lives? I was shocked more when they spoke during the research interviews.

What’s your take on authority before the making of the documentary and later?

Interesting… my take on authority in general is that it can get very dangerous without checks and balances. Authority that cannot be questioned is extremely venomous. History is such a great reminder of why you should never allow that.

See, if Veerappan had killed for pleasure or if he had been a serial killer, there would not have been so many layers. In his mind, he was questioning authority. He believed he was a keeper of justice. His belief that he was punishing the wrong-doers made this topic something interesting to attempt to understand.

Would checks and balances have prevented him from turning into this person? One thing is to point fingers and hope it won’t happen again. The second is to do something to prevent today from taking place tomorrow.

There is a certain disdain for the system if you’re not well informed. Once you read, you realise the system is superb, it is when human beings over ride it that failures happen.

In Veerappan’s case, some say that if the National Human Rights Commission had stepped in earlier and in a better informed way, the problem would have not prolonged.

Justice delayed is justice denied. The Sadasiva panel, set up to document human rights violations on people picked up in the hunt for Veerappan, submitted its report in 2007, but nothing much came out of it.

My understanding now is that people in positions of power need to be reminded of what is at stake when they ignore checks and balances. When these checks and balances are followed and the force goes about things scientifically, like Mr Vijaykumar did, officials were able to break into the network of Veerappan’s informers.

How have you reacted to the overwhelmingly positive reviews to the documentary?

I did expect some kind of disappointment from some, but the feedback has unanimously been positive. People who are a part of this seem happy to be identified with this documentary. They feel it is balanced. When officers tell me this, it feels good, because everyone has a take on it, and it is valid — some also feel it is tilted towards the government, but all acknowledge that we did our best and that we did not get into the show with a preconceived agenda. That makes me happy.

Was this educational for you?

Yes, it also triggered thought and told me I should read more and speak to more people. The people of the forest ask a simple question: whose forest is this? When outsiders can come in and take its resources, why can’t we? There’s no answer really.

Also, when it comes to Veerappan, there was a sense of wonder as to how he went about his life and survived in the forests for decades. If you dismiss his beliefs, you are not learning. It might be misplaced faith, but it lent him confidence. At no point do I want to rubbish anything. (It) all helped me understand the man better.

How do you want people to remember Veerappan?

I think people who take pride in the man will definitely do that. I think he should not be seen as a hero. I see him as a victim to a lot of things, one of them which is his own flaws. The others are social and economic disparity and abuse of power. I think his story is one that teaches us to be better as a society.

What I would have loved to document is his knowledge of the forest, be it a cure for diseases, knowing how to make a dessert using water and a leaf, or his understanding of that ecosystem. He would know if someone was coming in, from eight kilometres away. The years of knowledge he accumulated for sheer survival… Not documenting that is a missed opportunity.

Watching the documentary again, what are your thoughts?

It is the sum total of four years of work, and I had lost a sense of ownership. But I admired what I watched towards the end. When I see Anburaj, I see what Veerappan could have been. He might have been an elephant killer, he was also this symbol of machismo with Muthulakshmi, and flipped his heart bare for Anbu. Think of Anbu, he chose to be with Veerappan, then served 18 years in prison, and still has some compassion. That compassion, especially for non-selfish reasons, moved me. They still have it despite all the brutality they faced.

I could not feature Navas much. He had people ready to die for him, he served with a real sense of service. He was the arch nemesis of Veerappan. He wanted to capture and kill Veerappan, unlike Srinivas, who hoped he could make him surrender.

I will consider the documentary a success if it triggers the right kind of discussions. I am not here to provide answers. You examine a story and come out with a certain undertaking. If you can distil it down to a few questions, I’ll be happy.

Premium

Premium