Wim Wenders' Perfect Days, And The Imperfect Solace Of Solitude

This is #ViewingRoom, a column by OTTplay's critic Rahul Desai, on the intersections of pop culture and life.

Last Updated: 03.38 PM, Aug 18, 2024

OVER THE YEARS, I’ve learned to like my own company. I’m at ease when I’m alone. My head feels like a semi-furnished home where the furniture keeps shifting; where the space keeps renegotiating its relationship with old and new objects. It’s intense and inert in equal parts, but it’s a home nonetheless. My mental demons are so domesticated that they wear pyjamas to sleep every night. In other words, I like thinking: overthinking, underthinking, imagining, assuming, remembering. I’m comfortable with silences, awkward and loaded. I’ve built my life around sustaining this attachment to myself. In my work: I write about movies from home. In my leisure: I swim, walk and travel solo a lot. In my bonds: My partner is also an introvert. Even in my isolation: I’m not addicted to technology, but on the days I am, I use it to watch other portraits of isolation — like wordless trekking, camping and mountaineering videos.

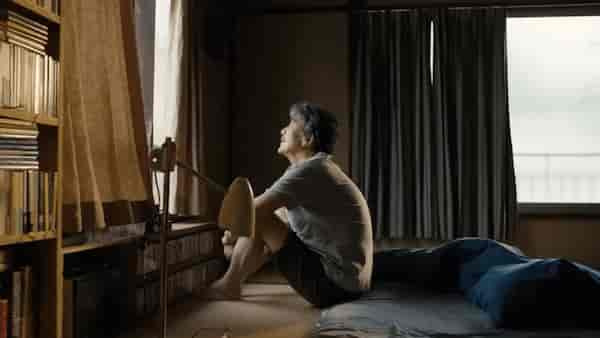

So when I started watching Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days, I felt both seen and restfully invisible. At first, the film looked like an uncanny window into my future. I knew I’d grow old(er) to be Hirayama, the 60-something public toilet cleaner in Tokyo whose seclusion unfolds like an analogue ritual in a digital world. It’s almost as though he turns the concept of urban isolation on its head. He lives alone in an ungentrified neighbourhood. He wakes up at the crack of dawn, and his body embarks on an expedition of muted muscle memory: brushing, dressing, smiling at a sunless sky, soda from the vending machine, drive, music in the van, work, lunch sandwich, photographs of reflected sunlight and trees, post-work soju, cycle to local bathhouse, read, dinner, sleep. He treats everyday as a perfect day — perfectly similar, perfectly felt, perfectly content, perfectly familiar and new at once. Hirayama somehow manages to merge the regimented rigour of living with the tempered curiosity of travelling. In arguably the most tech-forward country on the planet, he holds on to books and audio cassettes and film cameras. It’s an oasis of self-imposed wilderness in a jungle of mutated civilisation. Even his dreams are black-and-white, flickering 16mm visuals. For him, solitude is nothing but loneliness in love.

Hirayama’s anti-story is the indictment of an era where community and chaos are such default settings that insulation has to be earned — and romanticised. Most of us ‘escape’ or go on natural retreats to reclaim the agency of being alone. Self-care becomes a hash-tag. It is always a break from regular programming, not regular programming itself. We’ve convinced ourselves that the best way to live is to continue; that pockets of stillness are stitched into the fabric of motion. To see Hirayama find joy in small things and embrace the poetry of repetition is to reframe the fuel as an extension of the engine. Watching him on loop validated my choice to stay remote within the social parameters of survival. In fact, the look of fulfilment on actor Koji Yakusho — where the only speaking he does is within — moved me to tears. I’m on my way there, I thought, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Look how gratified he is.

Then comes the second hour of Perfect Days. Little by little, Hirayama’s detachment is infiltrated. His young assistant annoys him. His assistant’s girlfriend affects him. His van runs out of gas. He indulges in a game of tic-tac-toe with a stranger on a piece of paper hidden in a stall. His runaway niece gatecrashes his life. His estranged sister meets him. His emotions betray him. He drinks beer by the riverbank and plays shadow-tag with the dying ex-husband of the owner of the restaurant he frequents; he dodges shadows rather than capturing them on film. In other words, he is no longer in control of his vacuum. In this context, the remarkable final shot of the film — Hirayama tearing up on his morning drive while Nina Simone’s ‘Feeling Good’ plays on his stereo — can mean two things. The compulsive loner in me wants to believe that Hirayama’s monk-like resistance is broken. Years of self-preservation melt away. He is defeated by the persistence of the universe that he had so elegantly shielded himself from. It is then a tragedy, as if to confess that emotional celibacy is impossible to nurture in an age of social anxiety. It’s almost as if his man-made withdrawal is slowly subdued by the organic isolation of a post-pandemic planet. He cannot withstand the inevitability of feeling anymore. Hirayama might be isolated, but he does not exist in isolation.

But the alternate meaning is harder to confront. What if this final shot is a hopeful one, a happy one? Perhaps it’s at this moment Hirayama discovers that he is no longer immune to the inevitability of feeling. Perhaps this is when he senses that he is liberated from a facade of organised loneliness. Maybe it’s the film admitting that he had distanced himself not from humans but humanity itself; he was so busy being aware of the world around him that he had stopped being alive to it. Maybe Hirayama had been so stubborn in his desire to enjoy the simple pleasures that he had subliminally forfeited the simplicity of desire. The first hour — sublime and soothing — was actually the sad part. This essentially implies that emotional celibacy is not impossible but unfeasible; it’s healthy until it’s not. The tic-tac-toe, the niece, the assistant, the sister, the shadow tag moment — they combine to restore him rather than disrupt him. He realises that he was missing out all along; his loneliness was merely pretending to wear the robes of solitude.

It’s hinted that Hirayama’s reverie, too, is a reaction to some personal history. Maybe an abusive father, perhaps the death of a soulmate, maybe a petty family feud. For someone like me, it’s a difficult truth to swallow. But it’s a necessary one. This interpretation of the film suggests that some of us resort to loneliness as a trauma response. And once that happens, we have no option but to decorate the lifestyle and rationalise the idea of social confinement: stay reclusive, watch sunrises and sunsets, fetishise it, take photographs, be aloof, people-watch, go to cinemas and restaurants alone, relocate to beach towns or hill stations. We commit to it so hard that we feel obligated to destigmatise the culture of isolation. The result is overcompensation: self-sufficiency is advertised instead of normalised.

I’ve found myself in this position for years. I conveniently forget that my affinity for my own company was borne out of compulsion, not choice. I wasn’t always like this. I was the popular kid in my colony. I was chatty. I enjoyed being visible. But I spent so much of my childhood trying to perceive my parents’ dysfunctional marriage that, at some point, I started shutting myself off from my immediate environment. I stopped relating to people and therefore justified the habit of getting comfortable with myself. In the process, I probably missed dozens of potential human connections. I became so busy selling myself the notion of an introvert that I failed to recognise newer opportunities of attachment: a stranger on a train, a sobbing moviegoer, an estranged uncle, a renewed cousin.

It got worse after I lost my closest friend to cancer last year. Earlier I’d at least find little joys within my limited means. Now even the manufactured serenity of such days had disappeared. His sudden absence gave me an excuse to dig myself a deeper hole and call it a bomb shelter. My partner worried for me; my parents fretted about how I became even more reserved. But brooding became my cape; I coped by defending my void. When I watched Perfect Days at a film festival, I saw it as a moving endorsement of my grief. Hirayama felt like a kindred spirit. I was so taken by the tone that I rushed home to write about it. But somehow, I didn’t find the words. The timing felt off. So I sat on it for months. I thought about the piece, but something told me that I needed to be distant enough from the film — and the man I was — to view it beyond the obvious links.

The headspace feels right to do it today. It could be because I’m in between jobs, with the bandwidth to tackle such thoughts. It could also be because life has kept happening to me, puncturing my ritualistic bubble and pushing me out of the shadows. People have reached out and encounters have materialised. For once, I’ve not resisted. In the last two weeks, I’ve stepped out of my house no less than ten times to catch up with different faces — friends, former friends, acquaintances, ex-colleagues. None of this was planned. It started out as minor annoyances in my routine, but it soon morphed into that routine. It sounds exhausting, yet I’m reacquainting myself with a vocabulary I had previously forsaken. My film — like Hirayama’s — is camouflaged in the folds of other films. I wouldn't understand my quarantine if I didn’t know what I was shunning.

On my way back home, I often plug in my earphones and listen to music. I relive a random memory of my friend and wonder if I’m sad or happy about the imperfections of such days. I look out and notice the fleeting oddities — teenagers on their phones; office-goers syncing strides with each other; taxi drivers pursuing conversations — of Mumbai. I notice how loud loneliness can sound; how far proximity can feel; how blissful grief can look. I wonder if I’m allowed to ‘feel good’ because of other people and not despite them. Then I reach home, watch reels with my partner, go to bed and dream in digital resolutions. When I open my eyes, I wonder in my best Nina Simone voice: Is it a new dawn, a new day, a new life, simply by virtue of waking up? Over the years, I’ve learned to question my own company. After all, solitude is a language that swings between soliciting contact and seeking solace in none.

Premium

Premium