The Wild Robot Is A Heartfelt ‘Factory Reset’ Of Storytelling

The Wild Robot takes you back to the early days of Finding Nemo and Wall-E, where the joy is rooted in the innocence of imagination rather than the responsibility of the movie-going experience.

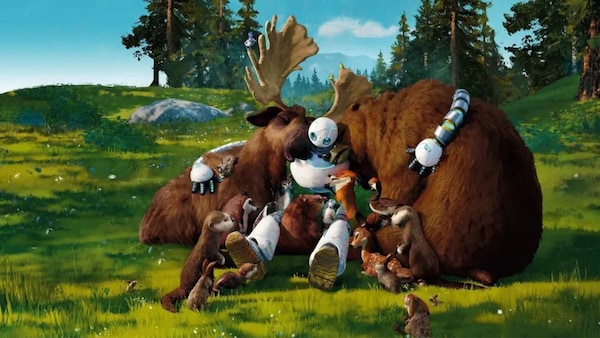

Still from The Wild Robot via Universal Pictures

Last Updated: 08.57 PM, Oct 18, 2024

THE WILD ROBOT is about an all-purpose robot that turns sentient in the wilderness. After washing up on a forest island, Rozzum “Rozz” 7134 learns to feel and discern once it mothers an orphaned goose and befriends a red fox. I’d say it becomes human, but in the context of where we are today, “it grows a heart” is more accurate. The premise is not earth-shatteringly original; cautionary and cute robot tales are the cornerstone of animated cinema and science fiction. A machine coming alive through motherhood is a familiar allegory. An unlikely ‘interspecies’ family is the core of cross-cultural comedy. Ecological fairy tales and deforestation metaphors featuring animals joining paws, claws and wings to defeat manmade evils — we’ve seen it all before.

Which is to say: The Wild Robot is very simple. But it's this simplicity that is the point. Like its protagonist, the film itself is definitive proof that no matter how much technology evolves, it cannot override the austerity of love. In the age of artificial intelligence, heavy metaphors and VFX-heavy spectacles, there’s nothing like a story that commits to the basics — the inherent wonder and the inbuilt fantasy — of animated storytelling. The hand-painted images, the disparate personalities of the characters, the all-ages writing and the utopian relationships reclaim the focus of the genre.

The Wild Robot revolves around the qualities we often forget in pursuit of complex feelings and twisted ambitions: kindness, care, tolerance, peace, adaptation and identity. Rozz is manufactured to serve the human race, only for “it” to become a “her” that imprints on the jungle instead. She goes rogue for daring to feel, an act lost upon her inventors in a world replete with genocide, war, religious conflict, capitalism and fascism. In a journey that’s as poignant as it is funny, she unites different species by breaking the rules of her programming; her artificial intelligence slowly mutates into emotional intelligence. The only time we see the human world, it’s the headquarters of Universal Dynamics, the evil-castle company that rolled out the robots that will ultimately widen the social gap between man and beast: humans will become colder and more automated, while animals will grow closer in their fight for survival.

Lupita Nyong’o delivers one of the more impressive voice performances in modern film as Rozz. The cultural commentary and battle for identity are embedded in the casting of a Kenyan-American actress; you can literally hear the robot softening as it goes from a lost machine to a reluctant parent. Her subtle inflexions and intonations transcend a typical “robot voice,” lending Rozz the kind of inevitability that distinguishes a saviour tale from a coming-of-age one. Among the others, Pedro Pascal is wonderfully at ease as Fink, the sly but secretly lonely red fox who flits between co-parenting and primal instinct. There are other famous names playing opossums, grizzly bears, beavers and falcons, but the unvarnished charm of the film lies in just how unassuming — and worryingly convincing — these ‘roles’ are. They blend into director Chris Sanders’ raw and childlike vision, which works as a welcome antidote to the slick sophistication of Pixar movies. It takes you back to the early days of Finding Nemo, Shark Tale and Wall-E, where the joy is rooted in the innocence of imagination rather than the responsibility of the movie-going experience. The message doesn’t shape the entertainment; the entertainment is the message.

Another thing this simplicity allows for is direct resonance. For instance, I couldn’t help but think of my own mother who, much like Rozz, broke the shackles of preprogrammed Indian womanhood to raise and protect me. Despite being conditioned to “follow orders” and “complete tasks” in a patriarchal setting, her motherhood empowered her to be that outlier, exit a troubled marriage and give me the wings I needed. It might sound like an old cliche, but it took me years to realise that this is her life and her story — I’m just the words in it. The identity crisis of the goose and Rozz’s struggle to let go moved me to tears. There’s a striking scene where she climbs to the top of a mountain to watch her “son” migrate with his fellow geese. It reminded me of the night I said goodbye to my mom at a train station years ago. She was going to live with her cousin in Goa, because I had started to work and shared an apartment in Mumbai. She didn’t want to leave (she even asked: “Is that all the time we had together?”), but she did it so I could find my own tribe in a country epitomised by overprotective parents.

Displacement is a normalised tragedy in most parent-child journeys. It’s a fact of life that has often confused me: Is separation really the key to evolution? Rozz’s transponder signal is essentially a device to imply that most mothers return to a default state of adulting — a subservient condition in most cultures — during the empty-nest syndrome. But the goose’s return after migration also suggests that not all departures are permanent. My mother eventually returned to Mumbai, and The Wild Robot — through its dazzling climax of forest fires and potential destruction — has the courage to question the role of an ageing parent in a liberated child’s ecosystem. Rozz’s sentience is what she values over her presence; despite a ‘factory reset’ and a shutdown of her system, her love and memories remain an inextricable part of her flesh-and-oil being. She is aware that the longer she stays with her son, the less equipped he will be for the future.

Another bond in the film caught my (wet) eye. Fink, the mischievous fox, uses humour and nihilism to camouflage his attachment to Rozz. That a wily and deceptive beast discovers a sense of truth is, in itself, an arc to behold. Fink is the “comic element” in a narrative, but one of the most poignant moments features him breaking down at the prospect of Rozz’s departure. It isn’t a loud breakdown either. He only croaks: “What if I have to tell you something and you’re not there?” His voice is deflated; it’s one friend wondering how he will survive without the other. She has changed the very core of who he is. Fink’s despair is relatable in a hyper-connected world where real friendships happen to us while we’re busy making other plans. It reminded me of how, over the last 18 months, I’ve often typed text messages to my best friend without expecting a reply. I’ve had so much to tell him, but he isn’t there. His death last year forced me to realise my greatest fear. He made me a better person — and left. I have nobody to share that mutual betterness with. Fink is, of course, consoled by the rest of the animal kingdom; the grumpy bear promises to be around for him if he feels alone. That’s a “sadly ever after” of sorts, because you know and I know that nobody’s going to fill that void. But at least the bear steps forward; there is a show of intent and empathy from someone otherwise incapable of being that way. I’m still waiting for that. Most people have been frightened by my grief; the isolation has only increased. But then again, we are humans. And humans are the least sentient beasts today. After all, we thrive on mistaking consciousness for having a conscience.

Premium

Premium