The Remarkable Life Of Ibelin: The Retroactive Stillness Of Grief

Director Benjamin Ree uses the investigative form of a true-crime drama. Except, the twist in this documentary is that the victim was actually a survivor — the grand revelation is life, not death.

Promo poster for The Remarkable Life of Ibelin.

Last Updated: 12.27 PM, Oct 29, 2024

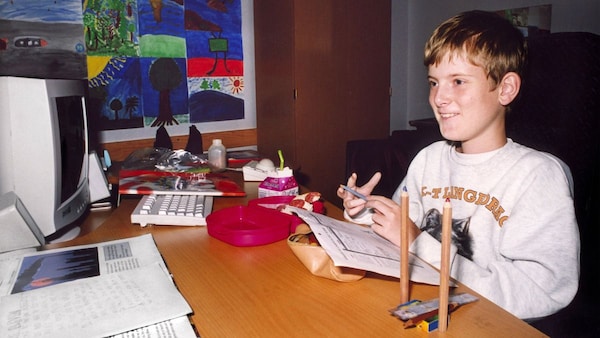

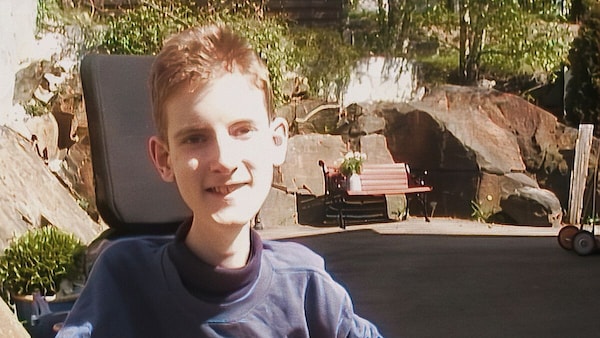

Benjamin Ree’s The Remarkable Life of Ibelin starts off as a documentary about death. We see the tombstone of Mats Steen, a Norwegian boy whose body and soul were at war. A mix of VHS footage and family interviews then reveals that Mats had duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a degenerative disease that reduced his 25 years to a hellish survival story. His mind yearned for the momentum his muscles never had. Subsequent clips show his body shrinking on landmarks and vacations, the end inching closer. When Mats finally succumbs, it’s 2014; his parents and sister are trapped in the throes of fresh grief. They’re preparing for his funeral, but they’re also searching for the right reason — the hopeful words — to celebrate who he was. All they saw was a son and brother whose spirit was snuffed out. Mats is gone, his suffering has ended.

This is when the documentary comes to life. Mats’ family posts the news of his passing on his blog, and almost overnight, they are flooded with emails and letters from “strangers”. Slowly, they begin to get a sense of Mats’ legacy; they discover the heart within that fragile body. Like most youngsters of his generation, Mats was a World of Warcraft gamer. He spent years staring at an isolated screen; he had his own avatar, a strapping Viking-like hero named Ibelin. Unlike most youngsters, this world was his only world. Ibelin wasn’t his fantasy; he was his fantastical reality.

On the outside, all people saw was a boy and his computer in a bedroom that seemed to grow around them. But on the inside, Mats was living an endless life; he moved in pixels and felt in data. The multiplayer online role-playing video-game allowed him to forge flesh-and-blood bonds and relationships with fellow gamers. The emails and condolences come in hundreds, from humans who existed as inventive digital avatars of themselves. His family learns that Mats — Ibelin — was one of the most popular and loved characters in the game. He was the bright light of Starlight, a thriving ecosystem he co-founded. Everyone knew him. Suddenly, the family sees Mats as a friend and a man whose spirit was alive. They see him as someone who had desires and crushes, insecurities and heartbreaks.

Director Benjamin Ree uses the investigative form of a true-crime drama. Except, the twist here is that the victim was actually a survivor — the grand revelation is life, not death. Mats’ time as Ibelin is recreated as an animated story from thousands of hours of chat transcripts and game logs. This video-game aesthetic is disarming, because it challenges our relationship with fiction; a pre-existing narrative is painstakingly pieced together and evoked through Mats’ online experiences. The members of Starlight are interviewed, almost as if the film embarks on an adventure in search of the person it presents. The silhouette of Ibelin gently morphs into the shape of Mats’ coming-of-age journey. Ibelin does everything that Mats cannot do, and yet, Ibelin is everything that Mats is.

Ibelin is flirty, compassionate and intelligent. He falls in love with a leather-clad girl named Rumour, listens intently to friends, gets drunk at local waterholes, fixes the distance between a gamer mom and her son, and socialises like a handsome high-school quarterback. Some of the most moving moments are the ones where Mats is revealed as imperfect, not perfect; normal, not aspirational. If anything, he aspires to be normal. The documentary does well to register the humanisation of Mats — of Ibelin — in the context of his life. Ibelin is shown to be a bit of a womaniser; Rumour even catches him kissing another…player. Lisette, the Dutch woman who played Rumour, admits that she felt betrayed. Their bond suffers, and even though Mats isn’t around to speak of this phase, it’s clear that he is just another teenager confused about the physicality of real-world feelings. While this might have been a conflict point in most stories, it’s strangely uplifting here. It becomes definitive proof that Mats’ flaws, unlike his body, are not differently abled. The moment he logs in, he is no longer special — and this is more of a triumph than a tragedy. Ibelin is no God, and Mats is not romanticised by virtue of being dead. He, too, can be just as unlikable as anyone else. In this case, it’s the sensitive thing to do; acknowledging his mistakes is better than canonising his strengths.

This ability to blend in, rather than stand out, is a privilege he chases. The documentary is surprisingly canny about the blurred lines between Ibelin and Mats. But it also implies that — despite Ibelin’s highs and lows — Mats’ condition remains inherent to his being. It’s a truth that he cannot outrun, even in a universe built on white lies. For instance, Ibelin has a routine: without fail, every single morning, he spends an hour running through forests and streets, castles and mountains. Just running, with the make-believe wind in his face, his limbs propelling him across environments. This is often seen from the perspective of other avatars, as if to not only hint at their curiosity but also underline the inescapable distinctions between Mats and the rest. It is a reminder that Mats' relationship with this “game” is very different: he lives there, the others are just visiting. He breathes there, while the rest are just exhaling. Running is muscle memory for his friends, but his muscles are running out of memory. The concept of motion is alluring to someone like Mats. That his body is shutting down in an outdoorsy country like Norway only informs the subliminal FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) behind his runs.

The interviews with other gamers suggest that they are average outcasts, internet geeks and socially awkward kids who choose a medium to be seen. Mats never had a choice because he didn’t have a world to escape from; Ibelin is both his life and his refuge. It’s why Ibelin is so alive, ubiquitous and charming — the stakes of simply being, for Mats, are higher than that of winning, warring or gaming. This dissonance between reality and expectations puts Mats on a collision course with the community he hides his condition from. He wants to continue being Ibelin — without the baggage and pitfalls of Mats — and finds himself avoiding real-world meetings and video requests. When they probe more, Ibelin lashes out at everyone and logs off for weeks. The spat is so natural that it’s heartwarming.

To its credit, the documentary resists the creative liberty of narrative punches. As dramatic as it might have been for the members to find out about Ibelin’s actual identity after he dies, it grounds his journey: he ultimately tells them in the game itself. No big sentimentality is attached to this moment. It dwells on the reactions a little, but you can sense Mats shrugging them off, apologising and moving on. For him, maturing and getting hurt are luxuries that he refuses to be defined by. His blog becomes quite the protagonist, revelling in the self-aware humour and entrenched irony of growing backwards. Consequently, the only question that emerges is this: Was Mats roleplaying as Ibelin or vice versa?

Ibelin’s inbuilt persona is so intense that it does what most computer-screen thrillers strive to do — it erases the gap between storytelling and modern living. Mats’ family rarely saw his tryst with technology and gaming as anything more than a welcome distraction. Yet, the letters and tributes point to a sort of immortality that transcends tags like 'online' and 'offline'; Mats lived harder and deeper than them, nurturing a soul that perhaps didn’t need a body. The de-stigmatisation of digital existence isn’t central to the film, but it surfaces through the expanding loss of a complex person. By the end, it’s hard to remember the image of Mats Steen alone in his wheelchair in a dark room. What stays, instead, are images of Ibelin sitting alone by a mighty lake and peering into the endless horizon. It’s hard to tell the imagination from the thinking anymore. It’s futile to tell the wish from its fulfilment anymore.

In any other year, this review would have ended here. But it’s 2024, the post-death era for a planet that’s not only coming off a pandemic but also grappling with an odd desensitisation of bereavement. We are more chiselled by the blunt knife of grief than ever before. So much so that, at times, it’s hard to separate the universal from the personal. Watching The Remarkable Life of Ibelin made me choke up, of course, but it felt like more of an accumulative response than a specific one. I’ve never been a gamer, but something about the online community in the film hits close to home. As a long-time introvert, the internet has been my primary source of contact and attachment. Right from the ICQ, Yahoo and MSN Messenger days, I’ve enjoyed the freedom of digital anonymity. Most of my romantic relationships have started as innocuous online chats. While I’ve never had an “avatar” per se, the internet version of me has more time to process, feel and formulate emotions without the pressure of live-action wit.

I can’t be anyone I want, but I can be myself in any way I want. So it’s a different, confident and more elaborate version of who I essentially am. Texting comes more organically to me than talking. This habit has also triggered some toxic traits over the years. I’ve often sacrificed authenticity at the altar of faceless validation. I’ve become so anti-social in person that I prefer something stranger than stronger. I’ve lost the ability to physically express myself. But my passion for writing — driven by the need to examine life a little alternatively — is a happy consequence of these digital footprints. It’s easier to be naked on paper because I can’t see who is watching. I owe my career to the long and random hours on the internet, chatting and searching and loving and waiting. Nothing has gone to waste.

Most of all, the documentary pushes me to trace the anatomy of losing my best friend. Grief is such a plural emotion that it’s more of a sound than a word. He was nothing like Mats; in fact, he was kind of anti-online and pro-person. The circumstances were hardly the same: cancer got him last year, so there is no direct comparison. But the prospect of dying democratises the will to survive. The Remarkable Life of Ibelin provides an insight into the endgame. He downplayed his cancer so much that it almost felt like a secret. We may as well have been in the dark about it. Mats didn’t want to be interacted with through the societal lens of disability, and neither did my friend. I did wonder why he wasn’t more open about his pain and challenges. But there was a magnanimity to the volume of information he shared — just enough to be cognizant, just enough to feel distant.

The cancer became an inextricable part of his identity, but he would rather discuss fantasy league picks, Messi’s World Cup heroics or future travel plans. Ibelin made it possible to fathom his frustration, too, during his recurring treatments. Even before he fell sick, his friendships and connections — like Mats’ all-consuming presence in the game — were everything to him. We played the game to escape; he played it to live. For some of us, he may have been a part of a week full of work and chores; for him, I suspected, we became his entire week. There was nowhere else to be. But somehow, he managed to find pleasure in the versatility of the week. He was never short of voices to hear. He was never short of minds to engage with.

Ibelin also offers me something else. Watching Mats’ family perceive a whole new dimension of him — watching them realise that he was immensely important and cherished and respected and known — speaks to the afterlife of my friend’s death. We were close for so many years that I often forgot he could be close to others. I only recognised the man he was to me. As a result, I’ve now spent the last 18 months uncovering his “Ibelin” — the brother and son he was, the football buddy and wise counsel he was, the childhood pal and discerning colleague he was. I’ve been looking beyond our transcripts, trying to learn more through people who knew him and felt his absence. I’ve chatted with his family and acquaintances in my pursuit of belonging to a wider community. Every conversation with them is a letter; every letter seeks a sentence. There are little pieces of him with everyone, like a phonetically distorted puzzle waiting to be solved.

A multidimensional picture of him — complete with quirks and flaws and incomplete love — is beginning to form in my head. I can’t believe how different he was, and how fundamentally similar he stayed, with separate sets of people. It has been nothing short of an adventure. Everyone is an animated projection of a bygone memory. It’s a bit like finding treasure chest after treasure chest in an extraordinary quest for ordinariness. Only, the person was the avatar all along. His truth was merely complimented by his fiction-sized reality. After all, the grief of losing my best friend is spiked by the thrill of deconstructing — and reconstructing — him.

The Remarkable Life of Ibelin is currently streaming on Netflix.

Premium

Premium