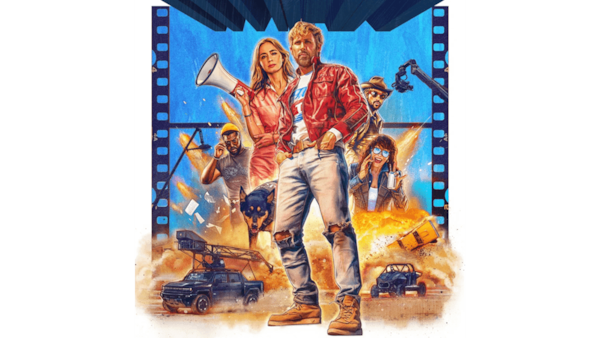

The Fall Guy: Ryan Gosling Is A Better Ryan Reynolds Than Ryan Reynolds

This is #CineFile, where our critic Rahul Desai goes beyond the obvious takes, to dissect movies and shows that are in the news.

Last Updated: 10.21 PM, May 05, 2024

“FROM the director of Bullet Train”: Now that’s a sales pitch. The pulpy and quasi-slick assassin comedy set on a Japanese train is best described as a proud lovechild of Quentin Tarantino and Guy Ritchie on steroids (if you think this is an exaggeration, wait till you watch the movie). It’s only fitting that adrenaline junkie David Leitch — uncredited for co-directing John Wick, mind you — is back with The Fall Guy, an affectionate and relatively saner ode to Hollywood stunt performers. Leitch’s nostalgia for his former profession — he was a famous stuntman himself — has long swung between serious sentimentality (John Wick, Atomic Blonde) and saucy satire (Deadpool 2, Bullet Train). It finds dual shape in The Fall Guy, a meta action parody that unfolds like an unruly sibling of Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time In Hollywood. The stunt double is the subject of this film, of course, but it’s the unsaid frictions — not the undying bond — between a wayward star and his stunt double that defines the goofy premise.

Eighteen months after a back-breaking accident on set, retired stunt performer Colt Seavers (Ryan Gosling) receives an SOS call from a troubled movie production. Action superstar Tom Ryder’s (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) producer Gail Meyer (Hannah Waddingham) lures Colt to Sydney by mentioning that the first-time director of this sci-fi romance is none other than Jody Moreno (Emily Blunt), Colt’s former flame and ace camera operator. Once he reaches, though, he realises that it’s not just for the job as Tom’s double. The crew is unaware, but Tom has apparently gone missing; two more days of absence would mean the studio shuts down Jody’s debut feature. Driven by love, Colt goes looking for Tom by night while rekindling his relationship with Jody by day. But he soon finds himself neck-deep in a conspiracy — one that cleverly echoes the role of stunt doubles as literal ‘fall guys’ for the big stars.

The Fall Guy is almost intentionally silly and corny, because it also functions as a wry takedown of bloated Hollywood epics. (The film within the film, Metalstorm, is expected to be a Comic Con all-timer.) It’s entertaining even when it’s in rubbish mode, so it’s sort of a win-win situation for everyone. In a way, Colt’s stunts on the film set — including a world record for cannon rolls, or doing multiple fire-ball takes for a salty ex — feel like rehearsals for the dangers of searching for Tom: A fake-sword fight at a condo, a drug-fueled nightclub brawl (featuring an imaginary unicorn), a dumpster-truck chase through town (featuring a dog that seems to be making up for the John Wick tragedy), a violent hunt for Tom’s cellphone, a deadly speedboat explosion.

In fact, the struggle to tell reel from real is the gag. Especially because Australian bystanders and authorities remain gloriously indifferent to the wreckage and chaos every other night — almost as if they assume they’re seeing that pesky American crew shooting again. It’s funnier that the ‘plot’ rests on deaths and cover-ups, which suggests the existence of an actual world with cops and prison sentences, contrary to the wanton recklessness of Colt’s mission through a foreign land. The gimmicks — split-screen phone calls, messy third acts, action-movie one-liners, tacky homages, slow-mo entry shots — are written into the film as part of its inherent cinephilia. At times, it’s a bit draggy, but somehow that ties into the film’s self-flagellating tone. The worse it gets, the better it gets.

Watching Colt juggle a love story with a B-grade action thriller is amusing because of one reason: Ryan Gosling. His bromantic chemistry with Emily Blunt aside, Gosling infuses Colt — and by extension, the film — with the sort of Kenergy he’s now synonymous with. Ryan Gosling often looks like he’s spoofing our perception of Ryan Gosling; his vibe is that he’s trolling — and deflating — his own perceived masculinity. As a result, the irony of being an A-lister playing a fictional stuntman whose action is executed by a real stuntman is never lost on him. The persona goes hand in glove with the character; Colt Seavers’ lack of self-importance is precisely what makes him the supporting hero of his own story.

Gosling also has this uncanny ability to burst the meta-bubble and flick the emotion-switch on between the deadpan giggles. He suddenly makes those La La Land eyes, croaks the Blue Valentine voice, rides that Place Beyond the Pines bike, moves that First Man hand — and suddenly you’re reminded that the character is a human and not just a playful Gosling gag. One might argue that the poker-faced self-punning comes too easily to him; it’s what his namesake, Ryan Reynolds, is often accused of. But it’s to the versatile star’s credit that, over time, he’s reduced stardom to a cultural punchline. There’s a sense that he is so secure about his craft that he enjoys disarming us with his dopeyness: “Look, devilishly handsome men are normal too, okay?” It’s like he can’t help but grin at the spotlight he receives — and perhaps that’s the coolest stunt of all. Colt Seavers could never.

Premium

Premium