The Court Is In Session: Judging The Most Realistic Malayalam Legal Dramas

Mainstream Malayalam cinema has finally evolved towards more realistic depiction of courtroom proceedings, after much trial and error.

Last Updated: 02.52 PM, Jan 04, 2024

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on January 4, 2023. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

IN the Mohanlal-starrer Narasimham, the sheer buildup accompanying Mammootty’s entry at a crucial juncture in the film was a master stroke. Supreme Court advocate Nandagopal Marar (Mammootty) charges Rs 1-2 lakhs per case. But of course that doesn’t prevent him from appearing at his best friend Induchoodan’s (Mohanlal) father’s trial. His intro is a quintessential playing-to-the-gallery moment, precisely timed to evoke thunderous applause in the theatre, more so when it heralds the rare reunion of two superstars on screen — Mammootty and Mohanlal.

Even to this day, Marar is considered one of the most exciting cameos in Malayalam cinema. Marar is also the most glorified representation of lawyers on screen, including the depiction of the proceedings in court. This includes his bombastic speech to the dramatic events that unfold that smoothly ensure Marar’s victory. “I liked that scene in Narasimham where the lawyer manages to call a bluff by arguing that the witness suffered myopia. That’s as close as one gets to reality. But please, you just can’t shout in court, whether you’re a lawyer or witness/accused in the box. You will be thrown out,” says real-life advocate Ninan John.

The growling, glaring and grunting of Adv Lal Krishna in Chintamani Kolacase, similarly, is a figment of the writer’s imagination. Also, you are unlikely to find a cocky lawyer like Aravind Swaminathan in Jana Gana Mana who reduces the judge and the court into mere spectators with his posturing. But these are the celluloid lawyers who have been celebrated on screen. Their dramatic dialogues created uproar, and victory was always guaranteed.

For the longest time, mainstream Malayalam cinema has glorified and dramatised courtrooms beyond recognition. Earlier, few films paid heed to demarcations like high court/sub court/magistrate/district court, etc. Probably the worst representation was of the judges — dreary, balding, over-the-hill actors who look like they are watching a tennis match in court from one lawyer to the other. As Malayalam cinema evolved, so did courtroom dramas. The most recent instance is that of Jeethu Joseph’s Neru, for which — the filmmaker told this correspondent — he picked a metre between the dramatic and the procedural.

Here’s looking at some of the courtroom dramas/trial sequences that got it right.

Nna Thaan Case Kodu: Some of the best scenes in this Ratheesh Poduval film unravel inside a courtroom. When Kozhummal Rajeevan (Kunchacko Boban) decides to fight his case himself in court with the aid of a cop-turned-lawyer, we are inside a court that’s seldom shown on screen. You have ambitious and shifty lawyers, offenders, powerful and ordinary witnesses, and a formidable but witty judge who doesn’t allow anyone to override him in court. The proceedings are on point. Several minor cases are being tried in court and they are layered with a dash of humour that keeps us thoroughly invested in the narrative. It’s done without a speck of melodrama and that’s perhaps what works in this film’s favour.

Vashi: Directed by Vishnu Raghav, the film revolves around a lawyer couple who are struggling to balance their professional and personal space. And it is one of those rare Malayalam courtroom dramas that accurately depicts the court and its nitty-gritties. We have a young, ambitious lawyer who is desperately canvassing cases, and a female lawyer who is fighting to prove herself in a patriarchal workspace. The designations, the calm and low-key proceedings, the no-nonsense judge, and the everyday challenges are also finely drawn.

Mukundan Unni Associates: This narrative centres on a lawyer who handles fake accident cases (an unexplored area in this field) and will go to any lengths to get his way. That includes slipping a cobra into a colleague's car to kill him. Mukundan Unni is driven by a relentless greed to succeed, and he unapologetically goes about it, thwarting anyone who comes his way. It shows the dark side of a profession that has no space for losers.

Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hey: There is a fantastic courtroom scene in Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hey that makes plain, albeit with a smidgen of humour, the misogyny and toxicity of Rajesh (Basil Joseph). At the family court, when the female judge asks him what a woman expects from marriage, his answer not only elicits instant laughs but also seals the deal in favour of his wife. And the family court judge, as expected, plays the role of a mediator and settler.

Kaathal: The divorce trial of Mathew and Omana is depicted with subtlety, using long pauses and non-verbal communication to establish the tension. (Meanwhile, Ozhimuri is set in a different period that has an aged couple in court for divorce.)

Adikkurippu: This legal thriller has Mammootty’s Bhaskara Pillai getting involved in the case of a castaway that leads to the unravelling of the rich and powerful in the state. Though the court scenes are sporadic, they are depicted realistically, taking us into the nuanced functioning of a court. Even as the narrative retains this inimitable balance (leaning more towards realism), the dramatic events that unfold make sure that we are in for an engrossing time.

Saudi Vellakka: The only silver lining in Saudi Vellakka is the long-drawn court proceedings that are kept realistic. An old woman is being tried in court for harming a boy in her neighbourhood. The case drags on for years, underscoring the delays in the judicial process in India. The judges, witnesses, and other issues keep delaying the case. What lingers is the desolate image of the frail old woman who has come to terms with her routine court visits, aware that mere remorse can’t undo the damage of her act. Factually, the art direction cannot be faulted in how they project the lower courts/magistrate courts. They are very stuffy with evidence materials, and sparsely built, with even the lawyers finding it difficult to get a foot in.

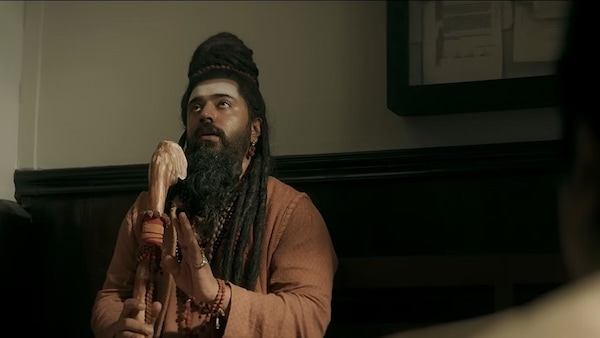

Mahaveeryar: In Mahaveeryar you get a fantasy courtroom drama that serves as a link between two eras. So when a mediaeval king walks into a modern court flanked by his subjects and guards, an oddly convincing unification occurs there. Meanwhile, you have cases peppered with humour, and a bit of drama. The king is facing trial for allegedly torturing a young woman in his chamber and during the cross-examination, the law points and arguments somehow transcend time and space. That includes addressing consent and the burden of proof in rape cases. Her confessions are manipulated, and she is slut-shamed in court, thereby reinstating the reality that women’s plight in society remains as mediaeval as ever.

Garudan: A senior cop and a teacher are the thick of things, with the latter convicted of rape and murder. But the teacher comes back after his life term to reopen his case. He decides to argue his case and also wins it, leaving the cop flummoxed. Though the court scenes do throw up some surprises concerning the different facets of law, the film itself required better staging and drama to sail through.