Swatantrya Veer Savarkar: An Inflated, Provocative Piece Of Propaganda

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative over new Hindi films and shows

Last Updated: 03.09 PM, Mar 23, 2024

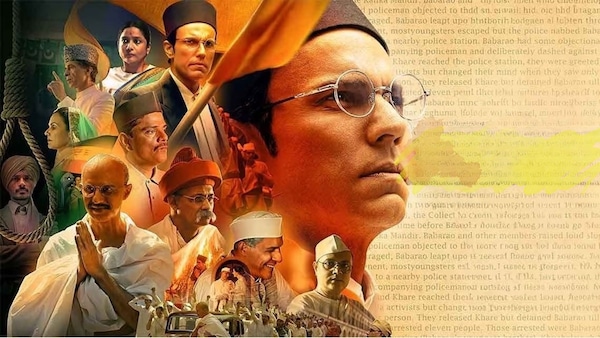

RANDEEP HOODA’s Swatantrya Veer Savarkar, a biopic on the contentious and polarising politician and activist, is everything one expects it to be. The film is an inflated piece of propaganda that bares its fangs to incite, provoke and incense. It distorts facts freely, elevates Savarkar to a degree above reproach or query, and reduces a complicated life story to a one-sided retelling with flattened principals and a diluted core.

This, of course, is nothing new. Hindi films for long have had a biopic problem which manifests in deifying the central protagonist with unquestionable veneration. The gaze towards the person is so elevated that all curiosity diminishes into impression. Hooda reiterates this approach. His indulgent film, which he has written and directed, is aesthetically and narratively inclined towards propping up Savarkar(essayed by the actor himself). During its sluggish runtime, Swatantrya Veer Savarkar makes space just for Hooda as Hooda makes space just for Savarkar. It is only his face that is perfectly lit while the others languish in darkness. Ankita Lokhande, who plays his wife Yamunabai, gets two and a half lines; Amit Sial, who plays Savarkar’s elder brother Ganesh, suffers the same fate.

There is a sickening vanity to Hooda as a filmmaker and performer, matched only by the way he chooses to depict the man at the center. There are no questions asked or aspersions raised. During the initial stretch of the film, Hooda as Savarkar keeps forming underground meetings every time he spots at least two people. Later, scenes after scenes are dedicated to portraying the time when Savarkar was in the Cellular Jail in Andaman (he was imprisoned in 1911 and remained there for a decade), highlighting his struggle and strife, and reducing what any other freedom fighter was doing at that time to a footnote. In a sweeping statement, the British officers keep talking among themselves (loud enough to be heard) that although they have kept the Moderates engaged in talks, the hardliners (Savarkar being one among them) are hard to distract.

Hooda snatches everything from the 1957 mutiny, 1897 plague, Queen Victoria’s funeral (1901), World War II, India’s independence in 1947, right until Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, and uses every historical juncture as means to an end, namely, to mine his protagonist’s heroism. In his retelling, Savarkar is the forgotten hero, the one man who influenced legions of freedom fighters like Bhagat Singh, Khudiram Bose and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. It is worth mentioning here that in 2023, days after the trailer of the film was released, Bose’s grandson Chandra Kumar Bose had debunked these claims, calling Savarkar “a Hindu fanatic who was thinking about the two-nation theory even before Jinnah raised it.”

But embellishments and not facts are Swatantrya Veer Savarkar’s concerns. Thus, it includes the episode when he swam to France while he was being extradited to India from Britain. And also claims that the political leader wrote multiple mercy petitions from the Cellular Jail to the British rulers, not as means of apology as was commonly believed, but to outsmart them and more crucially, help the release of other political prisoners.

To reiterate, none of this is new. On the surface, Swatantrya Veer Savarkar does nothing that another Hindi film biopic has not done before. But the film also unfolds with a radical vengeance, a complete disregard for history and a provocative subtext that feels fresh for the peril it withholds. It is one thing to alter the past and quite another to completely rewrite it. It is one thing to make a hero out of a person and quite another to use that as a setting to vilify others and treat them as antagonists just because they do not suit your narrative. Everything Swatantrya Veer Savarkar does to dignify its hero comes with an unwritten agenda of reducing and villainising everyone else who did not agree with him.

The chief among them being Mahatma Gandhi. Their ideological rivalry is well documented in history but Hooda renders their difference in terms of morality. Gandhi, tellingly portrayed by Rajesh Khera (an actor with a legacy of playing villainous roles) is presented as someone who was a British stooge, a pacifier at best and an ineffectual man at worst. Hooda insists that during the freedom struggle it was Gandhi who had an easier time due to his proximity with the British (the film, through its protagonist asks, “was anyone from the Congress imprisoned at the Cellular Jail?”) while Savarkar lost most of his life rotting behind bars. If Savarkar had his way, India would have gained independence long before it actually did. It is him who should be regarded as the father of the nation. In the film, both Savarkar and Gandhi wear similar spectacles and Hooda insists it is we who saw them wrong all along.

This triggering continues till the film opens up about Hindutva (Savarkar was the main proponent of it) and unravels as a bleak manifesto of the current government. Hooda does not care about subtlety anymore, or narrative manipulation to ease off the sharp edges of propaganda. We see Savarkar pacing up and down and stating what and who he believes to be a Hindu. Questions come from behind the camera and the actor breaks the fourth wall to talk to us, to tell us, to instigate us. Who is a Hindu? comes the query. “Anyone who considers India to be their fatherland is a Hindu,” he claims without dropping his gaze. “Are Sikhs Hindu?” comes another question. “They are the greatest Hindus.” Another question: “What about Muslims?” “If they share the same thought,” is the answer.

The most distressing bit is even this line of thought is getting normalised with repetition. Swatantrya Veer Savarkar opens with a caveat that says: “We have all been told that India got independence by non-violence. It is not this story.” Coursing through more than three hours, the film tells us that story – inflated, embellished, altered, distorted. Through it all, it keeps manoeuvring with conviction and maintaining that it is based on true events. In the screening I was in, people cheered when Gandhi was assassinated, and sighed when Savarkar was repeatedly arrested. It felt dystopian and like a frightening preview of a post-truth world we have come to inhabit where fiction can be curated as facts and we can be gaslit into believing it. In the larger picture, the more pressing question that emerges is not what a film like Swatantrya Veer Savarkar is showing, but what it is doing.

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of OTTplay. The author is solely responsible for any claims arising out of the content of this column.