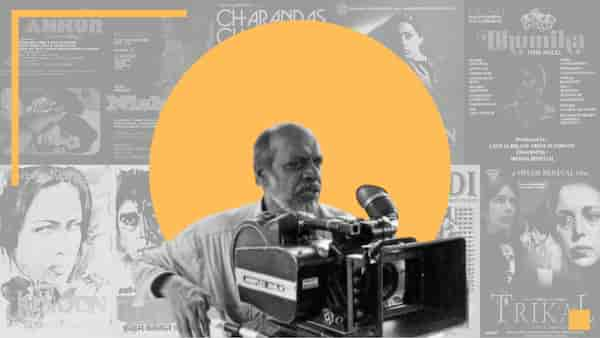

Shyam Benegal: A Master Archivist Of Indian Performing Arts In Cinema

Benegal’s cinema does not merely revisit the past — it actively keeps it alive, speaking to the present and future with undiminished clarity, writes Vikram Phukan.

Shyam Benegal's films are not just stories of their time but enduring testaments to tradition, history, and identity.

Last Updated: 07.02 PM, Dec 29, 2024

This column is published as part of our newsletter Stream of Consciousness on December 29, 2024. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

WHEN A BIG TREE FALLS, it leaves behind the soil it has nourished and the reverberations of a formidable legacy. As is wont, rather belatedly so, when a figurehead of cinema leaves us, Shyam Benegal’s passing sends us scampering to excavate his life’s work, striving to make sense of a distinctive oeuvre that remains unmatched to this day. Looking back, it is hard not to locate the auteur’s prime in the 1970s and 1980s, a period marked by his most influential works. These films continue to remain vital and relevant today, but beyond their narratives of political and social transformation, Benegal’s output serves as a living, breathing archive. This has much to do with the manner in which he seamlessly integrated Indian performing arts traditions into the very fabric of his films ensuring that they are not just stories of their time but enduring testaments to tradition, history, and identity.

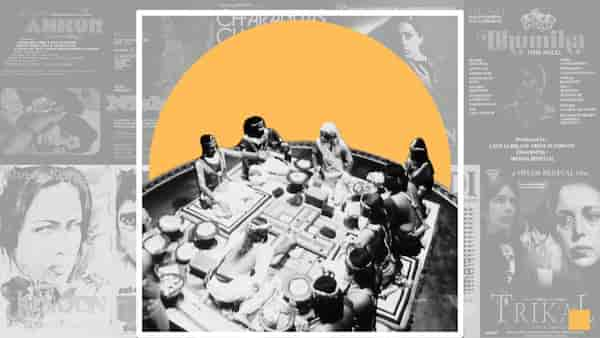

A treasure trove of this is, of course, the television series Bharat Ek Khoj (1986), an opus of many epics, that provided Nehru’s sparse prison manuscript a rich visual sweep and allowed the dramatis personae of history to fan out and inhabit a realm of vivid, living memory. Blurring the line between documentation and re-imagination, it revelled in its juxtapositions. For instance, Pandwani recitals by Teejan Bai serve as a telling backdrop to near-theatrical set pieces that distilled the Mahabharata into just a few stirring fragments. Or, Bhima’s blood-soaked vengeance is stylistically depicted by a powerful Kathakali interlude. Elsewhere, the ritualistic staging of Christian rites in Trikal (1985), brought in the pomp and circumstance of colonial Goa and also the gravitas of a community in transition, aided in no small part by the pastor’s sermon (Salim Ghouse, also Kṛṣṇa in Bharat Ek Khoj).

In Mandi (1983), Ila Arun’s earthy renditions of folk songs ground a film about the labour of women of the flesh, while the Lavani sequence in Bhumika (1977)—‘Mera Ziskila Balam Na Aaya’—evoked the blood, sweat and tears of working women in the film industry. Charandas Chor (1975), the film based on the play by Habib Tanvir, blended folk idioms with sharp socio-political commentary showing how, in Benegal’s films, these traditions do not serve as ornamentation but as integral components of a narrative. Unlike many Indian films—think of Tamasha’s story-telling spectaculars, Haider’s splashy repurposing of Bhand Pather or the sensationalised Bhuta Kola of Kantara—that often present performing arts through an exaggerated (even diluted), stylized lens, Benegal incorporated these traditions with subtlety and authenticity highlighting the everyday resonance and raw vitality of these art forms.

It must be noted that Benegal was coming of age in an era when Hindi experimental theatre was undergoing significant transformation at artistic centres like Chhabildas, shifting from declamatory and didactic depictions to more subtle representations. It is a kind of theatrical realism evident in his debut feature, Ankur (1974), a departure from the melodramatic excesses of Hindi cinema, but also much less stark than the films of the Indian New Wave that gained prominence in the 1960s. In the film, the mundane and the quotidian take centerstage, and emotional authenticity (as embodied by leading lady Shabana Azmi) forms the crux of storytelling. Through static camera work, measured performances, and deliberate pacing, Benegal crafts the intimacy typical of realist theatre. However, unlike stage productions, where the proscenium confines the audience's gaze, Benegal’s cinematic lens immerses viewers in the lived realities of his characters, blending theatre’s immediacy with cinema’s visual depth.

In Manthan (1976), set in rural Gujarat, Benegal draws on the participatory spirit of folk art forms to tell a story of collective empowerment. The song ‘Mero Gaam Katha Parey’, delivered with raw resplendence by Preeti Sagar, captures the folk timbre of the region. The film also follows the structure of folk theatre, focusing on community-driven storytelling and moral lessons. By using non-professional actors, many of whom were actual villagers, Benegal blurs the line between fiction and reality, highlighting his dedication to an authenticity that was never superficial. Through Manthan, he created a cinematic language that is as much about the people it portrays as it is for them, making the film a celebration of grassroots movements and traditional art forms. Benegal’s achievement received a touching coda at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, where a digitally restored print of Manthan was screened. This came almost fifty years after Ankur was presented in the Directors' Fortnight section in 1974, and Nishant (1976) competed for the prestigious Palme d’Or.

But it was Bhumika, arguably his finest work, that allowed Benegal to pay a metatextual homage to the evolution of Indian cinema as it follows prima donna Usha (essayed to perfection by Smita Patil) on her tumultuous journey in an imagined film universe, albeit one that drew extensively on the memoirs of Marathi actress Hansa Wadkar. The film lovingly recreates the shifting aesthetics on celluloid across decades, with cinematographer Govind Nihalani mirroring the transitions in raw stock and visual style in several black-and-white sequences, which transition from grainy textures to higher contrast, with sepia-toned visuals reserved for the reminiscences of Usha's childhood. Even the sequences on the film sets showcase a transformation from staged set pieces and performative acting styles to outdoor locations and naturalistic performances as the narrative progresses into the era of colour films. While this progression not only reflects the protagonist's rites of passage but also serves as a meta-commentary on the the medium’s evolution.

In these ways, Benegal’s cinema does not merely revisit the past—it actively keeps it alive, speaking to the present and future with undiminished clarity. In a polarised landscape, those who downplay this body of work do so to their own detriment. As both a document and a reflection of India’s evolving identity, his films remain an invaluable repository of the country’s social tapestry, offering future generations a vivid window into the past.

Premium

Premium