Park Chan-wook's Decision To Leave: In The Mood For A Love Story

Two soulmates cross paths in unusual circumstances, and it's this forbidden language of love — shaped by the investigative nature of modern dating — that Park Chan-wook beautifully reinvents in 'Decision To Leave'. Rahul Desai writes.

Last Updated: 01.24 PM, Feb 09, 2023

This is #CineFile, where our critic Rahul Desai goes beyond the obvious takes, to dissect movies and shows that are in the news.

***

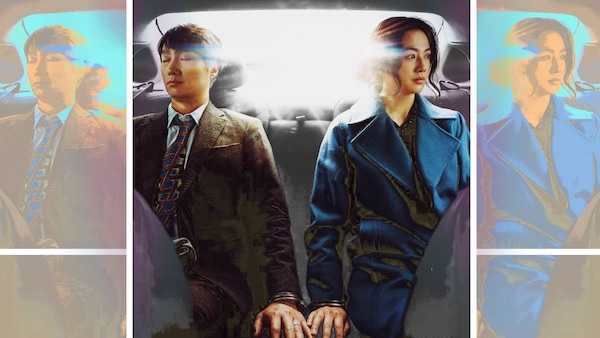

Park Chan-wook’s latest, Decision to Leave, is about a star detective who falls for an enigmatic murder suspect. The Busan-based detective, Jang Hae-jun (Park Hae-il), is in a reasonably happy marriage. But his wife works in a seaside town; they only meet on weekends. The suspect, Song Seo-rae (Tang Wei), is a Chinese expat and eldercare worker whose abusive husband is found dead at the bottom of a mountain he often climbed. She doesn’t seem particularly fussed about the ‘tragedy’. It looks like an accident or, at worst, a suicide. Hae-jun notices that she has all the quirks of a quintessential femme fatale — including a funny (Korean) accent. Yet, he gravitates towards her like a fly buzzing around a fresh corpse.

In other words, everything about the premise screams for the Park Chan-wook treatment. The twisted eroticism: They’re breaking the rules, so perhaps their sex — desperate, adventurous, risky — does the same. Maybe Seo-rae reverses the power dynamic and toys with the sensation of Hae-jun spying on her; she spices up his stake-outs. The stylised violence: Perhaps Hae-jun’s addiction to his job — the gory crime scenes, the psychological games, the unsolved cases that haunt him — feeds their dark desire for one another. Their edges fit, like shattered shards of glass fusing to form an unlikely puzzle.

But Decision to Leave is not that film. On the contrary, it is surprisingly quiet and tender. There is no torrid sex, and barely any bloodshed. Instead, its sensuality is derived from a sense of familiarity and solace, a bit like In the Mood for Love reimagined as romantic noir. Two soulmates cross paths in unusual circumstances, and it's this forbidden language of love — shaped by the investigative nature of modern dating — that Park Chan-wook so beautifully reinvents. It’s a language that’s more evolved than the subgenre of storytelling it’s trapped in — determined by not lofty words but instinctive gestures; not loud emotions but unsaid feelings; not reckless passion but hopeless compassion; not affair-like electricity but marriage-like tranquillity. The moment Hae-jun and Seo-rae meet at the police station, they seem to be way past the adolescent body-exploring stage; theirs is more of a mature, mind-discovering sort of chemistry. They react to each other like companions who just happen to be strangers.

In the interrogation room, the two take a lunch break like a couple who’ve been sharing space for years — digging into their sushi boxes in comfortable silence, before clearing the table with synchronised ease. Hae-jun’s secret surveillance of Seo-rae in her apartment involves him judging her little habits — watching television, smoking after meals — like a reproachful spouse. She wishes him Good Morning in his car every morning, instead of shooing him away. He thinks of her while his wife is on top of him, but through the lens of weathered longing rather than lust — like replaying the sight of her learning how to speak Korean from historical dramas.

Even the director’s trademark visual inventiveness is steeped in domestic harmony. For instance, Hae-jun keeps picturing himself in her private space. At first, this is a detective-like attempt to understand her better, to get into her head and retrace the steps of a potential suspect. At times, it even plays out like intellectual abbreviations of his insomniac mind. This soon becomes his grammar of intimacy — except it’s not smutty so much as strangely mundane. Like a smitten ghost he completes her manner of living: whether it’s holding an ashtray below her fading cigarette, or taking a hushed breath for her once she puts a client to sleep.

When she is cleared of foul play, the barrier between them melts. Yet, the intensity is old and cosy. He cooks and she chops vegetables while a song (“Mist”) plays on her phone; he pulls the dangling cigarette from her lips so that she can exhale before popping it back in. She cures his insomnia by helping him clear his wall of unsolved cases, little by little. On their visit to a Buddhist temple, he holds the umbrella while she reflexively reaches out for the correct pocket in his custom-made coat for lip balm and mints, almost as if she’s done this a million times before. It’s muscle memory without the memory. In turn, she holds the umbrella for him while he ties his sodden shoelaces — an image that finds heartbreaking circularity in the final moments of the film. Later on, their hands caress one another in a moving car. That she’s cuffed to him — effectively under arrest — is incidental; they converse like ex-lovers finishing each other’s thoughts and sentences. The handcuffs look like a metal promise that prevents them from drifting apart.

This language is rooted in the upending of the Park Chan-wook aesthetic. Love here becomes an extension of fixing, protecting and healing. The most romantic scenes of the film feature sacrifice rather than seduction; impulses rather than phrases. Like a workaholic detective defying his own being and telling a suspect to throw away evidence that might incriminate her. Like the lady relocating to the detective’s seaside town, knowing that he needs crime around to feel alive again. Like her getting caught up in a similar situation so that she can feel the anchoring rush of him ‘investigating’ her again. Like her draining a pool of bloody water before he arrives, not to erase evidence but because she knows that he detests the smell of blood. Like her snooping on him and recording observations on her Apple watch, just like he once did while surveying her. Like their urge to leave seeking the choice to return.

Given the linguistic ambiguity of love, it’s fitting that technology plays a leading role in the film. Their inability to fully grasp each other’s mother tongue gives them the agency to turn love into the film’s biggest mystery. As a result, they find each other in translation — in the pauses between texting and reading, Googling and seeking, interpreting and pre-empting. Voice notes become the cornerstone of narrative fate and personal faith. Fitness apps convey the calories of betrayal. Their stalking creates an illusion of scanning each other’s social media profiles for markers and clues, for confirmation of character and glimpses of memories they weren’t part of. Seo-rae’s casual response to Hae-jun’s stakeouts feels like the equivalent of clicking on his Instagram story after noticing that he saw hers. Hae-jun’s reaction, in contrast, suggests that he had long stopped scanning the names that clicked on his stories.

Much like millennials who’ve digitised the art of feeling into boxes and screens — screens that, as Kim Ji-yong’s stunning camerawork suggests, are as transparent as a corpse's rotting eye — Seo-rae and Hae-jun have forgotten how to express love without pushing buttons. Decision to Leave validates the vintage meaning of these buttons. They stumble in the snow and on beaches, in markets and at temples. It’s this stumbling — calm, crazy, ordinary — that keeps them haunted, and in perpetual pursuit of each other. They find ways to enunciate the broadness of belonging by escaping the shackles of articulation. That’s the tempered genius of Decision to Leave. It’s about detectives and detecting, about killers and martyring. It treats caring — in all its flawed and reflected glory — as the default version of companionship. It reframes the suspense of searching as the delirium of learning. After all, the decision to leave is defined by the yearning to stay.

Decision to Leave is streaming on Mubi.

Premium

Premium