One Hundred Years Of Solitude: A Miraculous Ode To Marquez's Magical Realism

Netflix's adaptation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez's masterpiece marks the tender coming together of an epic that values purity over prestige.

Last Updated: 01.00 PM, Dec 11, 2024

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on December 11, 2024. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

THE LIST OF POPULAR NOVELS CONSIDERED UNFILMABLE is probably shorter than the film adaptations that have tried — ultimately in vain. Cinema is full of examples where incisive and often whimsical instruments of literature have struggled to translate to the finality of an image. The vividness of the human imagination, after all, is greater than the sum total of tools cinema offers. Understandably, considerable trepidation and doubt prefaced the release of Netflix’s most ambitious long-form project yet — the adaptation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s seminal One Hundred Years of Solitude. The novel, which gave the world the idiom of ‘magical realism’; and which continues to be read, critiqued, interpreted and misinterpreted for its towering, ageless themes; appeared unconquerable. And yet, this is a portrayal that clinches the improbable… for it is grand, eerie, demanding, surreal and exquisite.

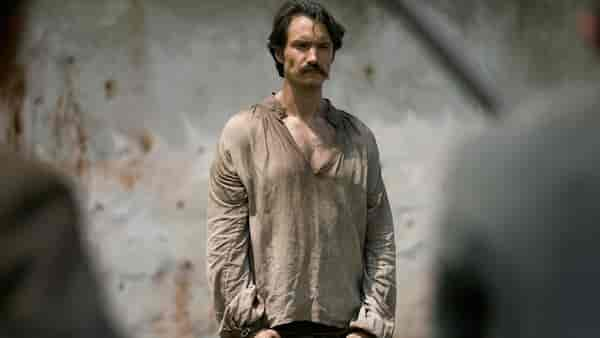

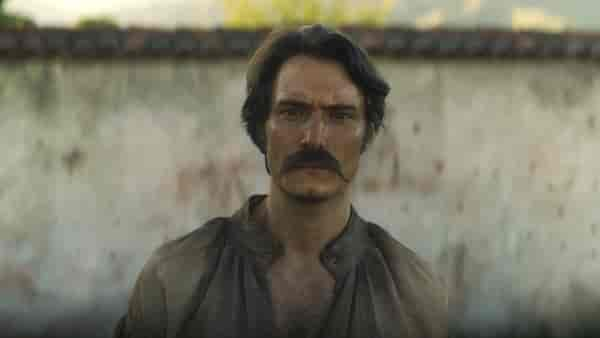

The Netflix series (the first of a 16-part run, each segment an hour long, is now out) charts several generations of the Buendia family. In the early 19th century, young lovers José Arcadio Buendía (Marco Antonio González) and Úrsula Iguarán (Susana Morales) leave their dilapidated village in search of brighter pastures. José embodies the stubbornness of a man far too ambitious for his own reach. Ursula, on the other hand, represents the more level-headed end of the pairing. After a moral tussle with the village, the two choose exile and lead a spirited quest into the jungles of Colombia. They walk, crawl, swim and drag themselves in circles, in search of Eden. Until José decides to construct his own — a place he christens Macondo.

Macondo is a literary totem, a word that exudes both meaning and metaphor. It’s the name Marquez gave to the town that José decides to build. The town that would become the centre of the novel’s many journeys outward. The site for generations of growth, trauma, love, decay, conflict and colonial upheaval. Even the thought of adapting a book that mixes reality with magical premonition, sight with sensation, religion with faith, democracy with civilisation and the human urge to seek discontentment, can cripple a person’s self-belief. It’s after all a novel that tells disparate but overlapping stories of a family, a village, a country and a continent. To Netflix’s credit it has placed its bets on a winning consortium of instinct and creativity.

The challenges were daunting. Consider the eccentric, inimitable tools that Marquez engineered for the purpose of the book itself: the slow trickle of a droplet of blood that informs a character about a sudden death; the first sighting of this wondrous element called ‘ice’; the blood-slicked surface of the sea; the countless apparitions that intercut science and magic. Images that thrive on paper, but could so easily be regarded as trite visual tricks. Here though, they seem glorious; effective yet controlled.

The imagery is a staggering addendum to the vast nativity of Marquez’s novel. Shot entirely in Colombia, the show never quite leaves the sultry backdrop of a land, seemingly transitioning from raw wilderness to the rattle of civilisation. And yet the show feels enormous in scope, sizzling in its density and so stunningly performed that it lingers long after the screen has cut to black. The fact that directors Alex Garcia Lopez and Laura Mora have gone with a largely unknown cast helps the story earn its currency. There is no sense of ‘now where have I seen him before?’, which makes the Buendias come alive, in all their despair, glory and violent contradictions. There is no weight of familiarity, but the tender coming together of an epic that evades prestige and goes for purity instead.

Unlike the novel, the series is wordy and uses a narration that helps link events, whimsical detours and the confusion between what’s real and what’s imagined. The assistance can feel like a hindrance at times, but in the absence of the book’s textual levers, it feels like a necessity. The fact that the show is shot entirely in Spanish can often leave the dubbing wanting but it only attests to the sincerity of a story that wants to stay true to its material. Maybe too honest, because the adaptation rarely swerves or challenges the notions of the landmark text or attempts to append its own ideas. Netflix, apparently, built three village-sized sets of Macondo, from swamplands, to infantile houses with thatched roofs to the arrival of Victorian designs and colonial infestation… A grand scheme for a grand-sized book.

Like the novel, the adaptation is a demanding watch. To cover the source material’s many ideas, some of them still being legislated inside literary courts around the world, the show plays fast and loose with the eternal ideas that makes great art sustain not just criticisms but decades worth of study, analysis and dissection. Much like civilisational manifestos, Macondo begins as this vision of innocence and cultural ingenuity. As the chapters of history accrue, and dirt and ambivalence piles up on the margins, the glitter of progress begins to fade into the chaos of a winding legacy. But is there meaning to life, to home, to heritage without the sense of an ending? “A person does not belong to a place until there is someone dead under the ground,” Marquez wrote. Civilisations are birthed by ambitious breakaway ideas. In this case, the thrilling release of exile. Except men don’t change, however far from the shackles of society they walk. They just think they do.

Premium

Premium