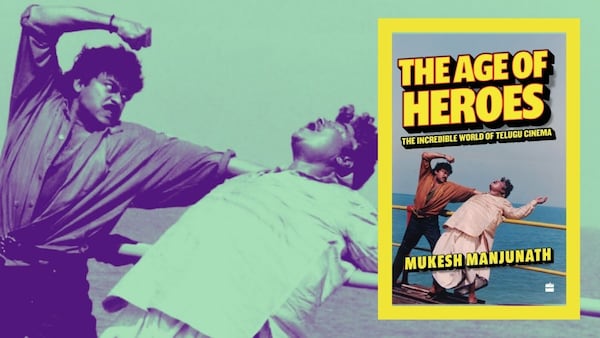

NT Rama Rao, Pawan Kalyan — What Makes A Great Telugu Cinema Icon? A New Book Explores

The Telugu hero is a character that spills over from myth onto the screen. The celluloid hero speaks and looks like us, but can perform superhuman feats. Read this book excerpt to know more.

Last Updated: 05.37 PM, Mar 26, 2024

Villains are sent flying through the air to pulsating guitar riffs. Socio-economic problems are solved with sermonising monologues. You can rest assured that good shall prevail—since the protagonist can change the world at will. We are in the presence of the Telugu hero: a character that spills over from myth onto the screen. The celluloid hero speaks like you and me and looks like us, but can perform superhuman feats.

'The Age of Heroes' looks at the historical-cultural factors that have produced cult heroes like N.T. Rama Rao, Chiranjeevi and Pawan Kalyan—and Vijayashanti, who embodies the concept of the female hero. With the growing popularity of Telugu films across the world, especially blockbusters like Bahubali and RRR, Mukesh Manjunath’s book—which won the inaugural HarperCollins–MAMI contest for writing on cinema—takes a deep dive into Telugu cinema, which entertains an audience close to 10 crores globally.

The following excerpt has been reproduced here with the permission of the publisher HarperCollins India.

***

Hero Introduction Shot

There are Pied Pipers waiting for us. They lure us out of our homes, and we follow them in swarms where we shed our money for them. We visit them with our families, with our friends and sometimes in dark corners with our romantic partners. Once seated, these Pied Pipers drag us out of our seats and lift us into a world whose grammar is flexible – much like their bodies. They dance, sing, beat people to pulp … they will defend the right and punish the wrong, they will show us the monuments of the world, they are willing to do anything to make people follow them. In their hands, the story-writing commandment of ‘the world changes the character’ is inverted and becomes ‘the character changes the world’.

These Pied Pipers, like the smell of ripe mangoes in the kitchen, waft into conversations with families in our homes. They seep into our fantasies once the lights are turned off. They sometimes exaggerate our flaws as well as society’s, like distorted mirrors do; at other times, like convex mirrors, they bloat our egos. They muddy our reality and make us glad it happened.

But there are many in this country who can do that trick. Bollywood has produced countless Kapoors, Khannas, Khans and Kumars who’ve made the nation dance to their tune.

But the Pied Pipers of Telugu cinema are different – because they want to pull one more trick, which separates the tricksters from the magicians. They are not satisfied that we paid money to watch their act and listen to their tune; they want us to pay with something more important than money – votes. When they plunder our political will at the ballot box, that’s when you know that they are the aiming for greatness. They will use every weapon they have – including their region, religion, caste, gender, their fathers and grandfathers. Some are successful, most come close.

These Pied Pipers in the Telugu states are called Heroes.

Song and Dance

The Telugu film industry, which produces the greatest number of films in the country, has a fascinating obsession with its masculine protagonists. While most begin as ‘actors’ playing a part in the broader story, as success beckons, the scripts begin to bend around these Heroes. This phenomenon is not the result of individual egos, but a cultural phenomenon that defines the state of the Telugu society today, and explores the cultural vacuum that Heroes, the ‘mass’ stars of the Telugu film industry, occupy and dictate.

Comedy Track and First Fight in a Strange Land

As with all catastrophes, the idea for this book struck me when I decided to tell the truth.

I was new to Mumbai and barely knew anybody in the city. In the process of making friends, I piled on to colleagues, friends of friends, acquaintances … and all this usually meant socializing with strangers, while feigning curiosity in activities in which I had no palpable interest. Loud concerts, eating undercooked dinners prepared by new friends and lying about its quality over the fear of losing a nascent friendship, watching experimental theatre where actors poured paint over each other to encourage thespian ambitions of friends of friends. In this process, questions would be asked of my work, my interests and, more importantly, where I was from. And I would always lie to these strangers who had the potential to be best friends – Hyderabad.

People would nod and usually tell me about the last time they were in the city. Some would extend a friendly arm by telling me how much they loved the biriyani from the city. I would lie about how my opinion concurred with theirs. Some would try to be cheeky and goad me by telling me that they preferred biriyani from other cities. I would pretend with equal cheekiness about how offended I was.

‘Facts don’t care about your opinions,’ I would say. Or if I was really trying to fit in and extract laughs out of the conversation, I would say: ‘The Nizams loved the biriyani so much, they didn’t conquer further south. My biriyani stopped wars. What did yours do?’

It would get the laughs. I would make a friend for the evening.

But if I were being honest, I would have said: I don’t care about biriyani. More importantly, I’m not from Hyderabad.

I continued hiding the truth – partly out of embarrassment.

Partly.

Until the day that I almost made a friend. Let’s call him Amit. He mentioned that the spelling of his name doesn’t end with an H. He accused South Indians of squeezing the alphabet into a name even when not required. I replied that I didn’t foresee a situation where I had to write his name down, but I thanked him for the information. Then he asked me where I was from, and I almost gave him the same answer I would always give. But this time around, I wanted to tell him the truth. I marvelled at Amit’s confidence as he ensured that I knew the correct spelling of his name, while I brushed over an important aspect of my life like it was a bald spot on the head. With a false sense of confidence, I told him the truth.

Anantapur.

Then Amit’s face froze – his brows furrowed while his brain tried to locate the place like a navigation system running on low battery. It scanned the map of the country – first checking around the foothills of the Himalayas; then dusting the Thar Desert, hoping it would be released; groping along the long coast of India, going all the way from Mumbai to Kolkata. For a brief second, he even glanced at the seven states in the northeast. Finally, he gave up what seemed like a futile search and reached into the interiors of India, like a magician looking for a rabbit that may have escaped from the hat. From the Ganga, he combed through till he reached the Narmada, his fingers caressing the Deccan Plateau like it was a big mole on clear skin, until he reached Kanyakumari. He peeked into the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, knowing full well that this would not be successful.

I wanted to help him.

‘It’s in Andhra Pradesh,’ I finally said. Without pausing for a second, Amit said: ‘Andhra Pradesh? I once took a train that went through Andhra Pradesh.’

Villain Is Introduced

Amit was only the final domino in this quest. It had taken years to come here. Maybe it began when I was reading my first ‘Indian’ book by a celebrated male Indian author – the kind who gets to roam with Hollywood stars and starlets – talk about Indian-ness by talking about Bollywood as Indian cinema. Or maybe it was in the way small towns were spoken about in Indian literature – emerging through streets in Uttar Pradesh, posters on walls in Bihar, quirky villagers in Tamil Nadu.

Maybe it had to do with names. Indian English literature had a standardized way of writing names: First Name – Last Name. Characters and their creators had stylized names in this fashion. But how could I make peace with this tradition? Where I come from, this tradition is flipped. Surname first and then the ‘first’ name. That’s how Telugu names are intended to be read, and to me, the ‘normal’ way feels as if one is being coerced into a headstand, talking to people’s feet and listening through their toes.

It could also be that Indian books that spoke about India harped on about India’s cities – about Mumbai’s maximum nature, its lanes and rum-soaked bars; Delhi and how each alley had a history, and any historian worth their salt fought over the origin of each brick and bridge in the city; Kolkata with its intellectuals; Lucknow with its poets, and Bangalore with its laid-back character like a beer-guzzling friend, who enjoys coding on breezy Sunday evenings. But what about the small streets? What about the gullies of Anantapur? Or any of the hundred small towns in the Telugu states?

Even if one looks at the map of India for long enough, it is still easy to miss these places, for there is nothing terrifyingly remarkable about them. They don’t have the metaphysical allure of the Himalayas or the expansive coastline of the Peninsula or the mystique of the northeast or the devouring fervour of a city from the Third World. They can’t even boast of the kingdoms and royalty that the Thar desert has to offer. Somewhere in the south-central region of Peninsular India, these places exist as trains and highways cut across them – as if God had doodled during a boring lecture.

Heroes are useful to understand these towns and its people, who are otherwise so easy to ignore. They are all unified in how much they worship their Heroes. They might not even be devotees to the same gods, but when a Hero walks on-screen, there’s unity. For two-and-a-half hours, at least.

- The Age of Heroes: The Incredible World of Telugu Cinema (Paperback | Non-Fiction | 208 pages | Rs 399) is published by HarperCollins India.

Premium

Premium