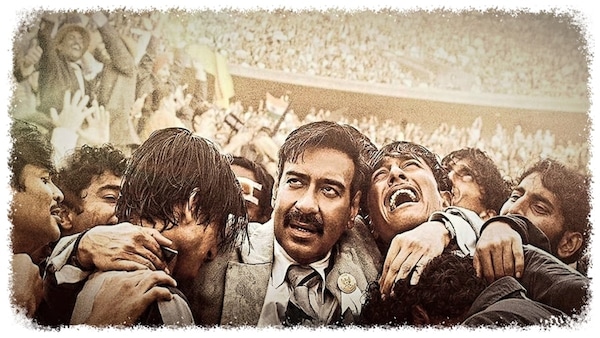

Maidaan: Ajay Devgn's Film Desperately Wants To Be Chak De! India

During its sluggish runtime of 181 minutes, Maidaan appears to be too caught up with the mythology of Indian football coach Syed Abdul Rahim to offer any real insights

Last Updated: 03.22 PM, Apr 10, 2024

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on April 10, 2024. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

AMIT SHARMA’s Maidaan desperately wants to be Chak De! India. The desire is not unfounded. The 2007 Shimit Amin clutter-breaking sports film revolved around the Indian women's national hockey team and, with time, has cultivated the legacy of serving as a blueprint for other outings of this genre. Sharma’s aspiration, distinct and discernible, leaps out in crucial moments — like a winning team taking a moment to appreciate the underdog; like an aerial shot of a beleaguered coach spending a wordless moment with himself the night before his redemption; like the same beleaguered coach risking his past for the future of a national team.

The problem with Maidaan is that it also plays out like every other sports film. The outline is so rigidly drawn that Sharma rarely, if ever, steps out. His resistance to be non-inventive results in tropey storytelling which is not necessarily a bad thing. After all, the sight of an underdog finishing first in a race can be repetitive but never monotonous. The filmmaker, however, colludes stereotypes with embellishment. As a result, every obstacle is dialled up to a life-threatening crisis, every contrarian person is painted as a caricature villain.

This empty reliance on melodrama is baffling because the story Sharma has chosen is tailor-made for film adaptation. Maidaan traces 10 years (1952-1962) in the life of Syed Abdul Rahim, the former coach of the Indian football team who was regarded as revolutionary for his tactics and approach. During Rahim’s tenure, the Indian men's football team scaled great heights, the highlights being their win at the Asian Games twice (1951 and 1962) and reaching the semi-finals at the 1956 Olympics.

Maidaan, which marks Sharma’s second collaboration with producer Boney Kapoor after Tevar (2015), is about the person behind the statistics. The film seeks to probe into the personality beyond the forgotten persona. But the writing (Saiwyn Quadras, Akash Chawla and Arunava Joy Sengupta are credited) offers no breathing space to delve into the brilliant mind. During its sluggish runtime of 181 minutes, Maidaan appears to be too caught up with the mythology of Rahim to offer any real insight.

Fairly early in the story, we see him travelling to different parts of the country and building a team (which comprised legendary footballers like Pradip Kumar Banerjee, Chuni Goswami, Jarnail Singh), but his reason for choosing them is glossed over. Ditto for his role during the matches. All we see him do is stand on the side, furiously smoke one cigarette after another, and gesticulate with his hands — all of which magically leads to winning results.

It is difficult to say what this role could have been in the hands of another actor but it gains little from the presence of Ajay Devgn. The actor plays it too straight, too smug, and later, too tragic to leave a mark. There is too much of Devgn in the character for Rahim to come through. It also does not help that he remains unconvincing as an athlete right till the end (Rahim passed away at the age of 53 — not too old), with only two scenes featuring him with the ball.

This excess in his portrayal (wanting to do nothing is also an excess of a kind) aligns with the stereotypes Maidaan freely mines. The Football Federation of India is reduced to a shingara-loving group with a herd mentality that can put Romans during the era of Julius Caesar to shame. The pack is led by someone called Shubhankar Sengupta (an awful Rudranil Ghosh) whose one-tone depiction is one for the books. The film wants us to believe that Subhankar detests Rahim because the latter does not favour Bengalis.

Same for Gajraj Rao’s character who plays an influential sports journalist with only mean blood in his body; he is also given a line that says, “Democracy is overrated”. But as the film unfolds, it sidesteps the primary reason for their animosity as it treats them as cartoonish stock personalities who remain unmoved even with the winning streak of the team. Their hostility feels all the more tepid for it remains uncoloured by religion. If the film wants us to buy the fact that they espouse groupism then it feels incredulous that these characters make no comment on Rahim being a Muslim.

Nothing in Maidaan feels enough. If someone has lung cancer, he needs to cough till every breath in his body is spent; if someone dislikes another, the resentment is marinated till it brims over as hatred. And when the time arrives to raise the stakes before the 1962 Asian Games finals, the film pulls out all the stops. There are protests in the streets, there is a man dying on the field, there is a minister unwilling to help… There are only problems.

Sharma’s dependence on plot decoration sidetracks from what is a rare Hindi sports film with incredibly shot scenes on the field (Tushar Kanti Ray and Fyodor Lyass are the cinematographers). It is during the matches that Maidaan comes alive, exhibiting a pulsating energy (evoked by the kinetic camera movements) that runs against the passivity of the story and the poor VFX. The film concludes with a rousingly-shot 1962 Asian Games finals at Jakarta with admirable resistance to cheat shots. It also helps that the footballers are essayed by actors (like Chaitanya Sharma, Amartya Ray, Sushant Waydande) who look consistently convincing.

But it is impossible to glean through the better moments in Maidaan and not agonise over the witless ornamentation. All that the makers had to do was let the story take its course and build an intimate portrait of personhood without reiterating the towering personality. By refusing to do that, Maidaan feels like an empty recreation of an era and not an urgent revisitation of a time.

Maidaan is currently releasing in Indian theatres. Here's where to stream it on OTT after its theatrical run.

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of OTTplay. The author is solely responsible for any claims arising out of the content of this column.

Premium

Premium