Lantrani: Kaushik Ganguly's Short Is The Standout In A Middling Anthology

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative over new Hindi films and shows.

Last Updated: 03.07 PM, Feb 10, 2024

LANTRANI, the new anthology on Zee5, boasts of one of the more interesting rosters in recent times. The filmmakers involved with the project comprise Kaushik Ganguly, a prolific voice from Bengali cinema; Gurvinder Singh, known for his brooding Punjabi language films; and Bhaskar Hazarika, whose 2019 outing Aamis renewed interest in Assamese cinema. They share linguistic differences but that’s not all. All three of them possess distinct narrative styles and their worldbuilding is as different as the worlds they belong to. The middling writing in Lantrani steamrolls their individuality, making one indistinguishable from the other.

The overarching theme, if probed a little, reveals itself to be a satirical take on the India we have inherited and the India we have come to inhabit. Understandably so, the pandemic makes an appearance, so does social prejudice. The growing tendency of the country to treat animals better than human beings occupies the narrative centrepiece in one of the shorts. But the treatment makes a world of difference.

In that regard Hazarika’s film, titled Sanitised Samachar, suffers the most. Set during the pandemic, it largely unfolds in a newsroom struggling to make ends meet. They have no sponsorship and the journalists are doing side jobs to keep things afloat. The intent is fairly evident: critiquing the eroding state of journalism where advertisements have become the news. Hazarika stages his outing with exaggeration. The background music is amped up, so is the commentary. The short opens with a young journalist documenting the empty newsroom (a makeshift and deserted office) with his phone and complaining that they do not have Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to go out and report.

But during its runtime, the excessive tonality comes to overwhelm the narrative and reduces the execution to a school-skit aesthetic. Take for instance the way we never see the face of the businessman who intends to advertise the sanitiser on prime time and compels the journalists to promote it as the one-stop solution to Covid. It is only his booming voice that fills the screen. And although the subtext is as clear as day — the facelessness of corporate dominance — the design is too amateur for a filmmaker like Hazarika. Or, take cognisance of the fact that there is a wheelchair-bound journalist whose inclusion appears to be oriented to a passing “wheelchair journalism” joke.

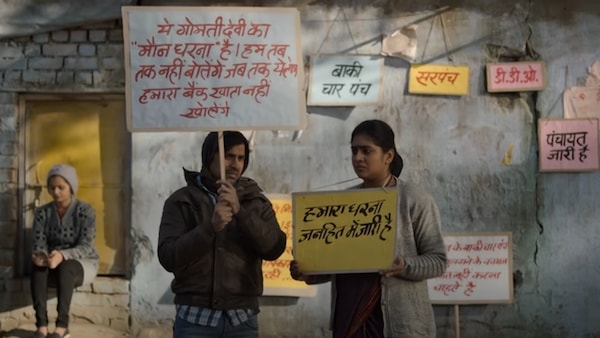

Singh’s outing, Dharna Mana Hai, fares better and has the bones of a good film. It centres on a couple who start a silent protest against the biased treatment they are subjected to. Gomti (Nimisha Sajayan of The Great Indian Kitchen fame) is a Dalit sarpanch who is frustrated by the non-cooperation of the male members in her pursuit of development. She counters with her silence and sits outside the office of the district development officer with her husband (Jitendra Kumar).

There is a nice rhythm to the proceedings which effortlessly weaves in the passage of time and the change in people’s perception towards the protest. Initially, the sight of Gomti and her husband attracts media attention but they soon become part of the street in a way that most things in the country do. They get sidelined in the larger scheme of things. But Singh is telling a tale of fortitude which is ably supplemented by the determined turn of the actors. Nimisha Sajayan’s face, capable of conveying countless emotions, plays a key role in this. The actor is eerily effective in all scenes that feature her. But the writing by Durgesh Singh (of Gullak fame) often leans on easy flourishes and glosses over complications, underlining that this is inherently a feature film crammed into a shorter time frame.

It is only Ganguly’s Hud Hud Dabbang where the form aligns with the story and social context makes a timely cameo. The film spans across a couple of hours where a police officer (Johnny Lever) on the brink of his retirement, is ordered to take a prisoner (a compelling Jisshu Sengupta), for a court hearing. The humour is built into the little things. Like the cop who spent years only maintaining mundane things at the station being entrusted with a bike and a bullet. Or that the inmate’s hands are tied with a long rope (handcuffs, one of them says, exist only in films) which Lever is supposed to pull. And that it leads to obvious physical comedy when one decides to use the washroom and the other washes his hands.

Lever is fantastic as the cop who is unsure of what to do with the new lease of responsibilities. His is an instance of inspired casting that adds immensely to the intent of the film. Ganguly seeks to depict a situation where a court hearing criminalises a man because of his sexuality but halts proceedings when a cow enters the precincts. That Lever, who has made a career out of displaying buffoonery on screen, portrays the more sensible enforcer of law highlights the point of Ganguly’s outing: the tragedy of our times is that the system is reduced to a joke and the jester cannot keep up.

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of OTTplay. The author is solely responsible for any claims arising out of the content of this column.

Premium

Premium