Kuttey Is A Student Project Disguised As A Film

Aasmaan Bhardwaj frames his debut film as a visually unremarkable noir comedy with no semblance of worldbuilding or intent.

Last Updated: 01.07 PM, Jan 13, 2023

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative about new Hindi films and shows.

***

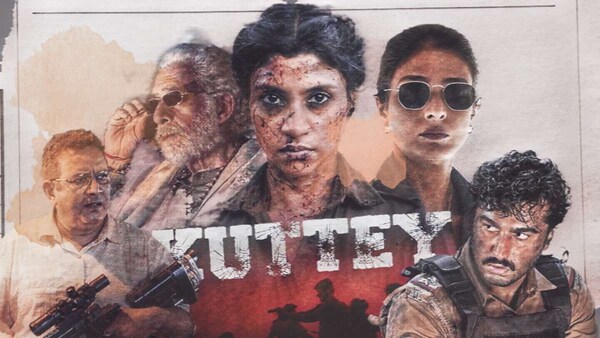

On paper, Aasmaan Bhardwaj’s Kuttey has a more enviable credit slate than most Hindi films can boast of. Sample the roster: Naseeruddin Shah, Tabu, Konkona Sen Sharma, Kumud Mishra, Shardul Bhardwaj, Radhika Madan and Arjun Kapoor. It is an interesting ensemble for its sheer diversity. Kapoor and Tabu occupy two ends of the acting spectrum: one barely emotes, the other can move mountains with her silences. The potential is enormous, the possibilities are endless. You put them together and by the virtue of their existence, something can come out of nothing. Which is not to say, they are immune to a bad script but that they are compelling to watch. Kuttey makes them look dull. Not all of them but most of them, most of the time.

Things in the film just happen. Characters come in and out of a scene, chaos unfolds. But the mayhem is so contrived that the outing’s pointed position remains of manufacturing and not inhabiting it. Then there are bullets. People are always shooting each other. This is not necessarily a problem but it is a marvel how ineffective they are. No one in the film dies when shot for the first time. And people get shot all the time. It is like living is an excuse for the characters to be killed.

Most of the narrative unfolds in the course of one night. A group of four people want the same thing: money. This includes two unreliable police officers Pammi and Arjun (Tabu and Kapoor), a young woman and the man she loves (Madan and Bhardwaj), who works as a thug for his father (Shah). There is also one honest officer Paaji (Mishra). On the fateful night, they all attack a van. In the broader picture, Kuttey is about India. It is a tapered recreation of the country riven with caste, class politics and disfigured by the insatiable hunger of those in power. This, however, remains an inference drawn from the narrative shards Aasmaan drops along the way and not the reading the film either demands or encourages.

Instead, the filmmaker frames his debut outing as a visually unremarkable noir comedy with no semblance of worldbuilding or intent. Not one shootout sequence stands out (Farhad Ahmed Dehlvi is the choreographer); neither does any one character. In a scene when Paaji asks his morally dubious colleague Pammi why she is doing what she is doing, she replies that she wants to sleep better. Government quarters are too small. Tabu can make even half a sentence sing but this line, the only hint at who she is, falls flat miserably. At several points in Kuttey, the overwhelming feeling is of watching the work of a director who has spent all his effort in getting his dream cast.

This inadvertently pushes one to confront Aasmaan’s access and privilege being the son of Vishal Bhardwaj. It is a problem not because it exists but because of what has come out of it. Granted this is his first film but his tone feels too derivative to register any mark. There is a bit of Kaminey and a whole lot of Tarantino. But on a more fundamental level, this hurts even more. Structured in chapters, Kuttey also seeks to make a comment on the India we live in. It opens in 2003 where Konkona plays the role of a Naxalite. This detail, which also comes back, is included as a checkpoint, an almost stand-in of an issue when in fact it is an issue. The lines are never not broad. Mishra’s character, the only faithful man in this land of traitors, is not given a name. He is referred to as Paaji and later, more directly as Sardaarji. If Kuttey is about community politics, its edge is as blunt as an old knife. It unfolds like an incoherent rambling of a non-resident Indian when they detail what’s wrong with the country. The demonetisation mention at the end, which lands as a WhatsApp forward, only clinches this reading.

In the capacity of a director, Aasmaan thanks a host of people for the film. The initial acknowledgement cards run for more than three slides. At the end he expresses gratitude to his professors at NYC. This would have been sentimental if it weren’t so telling: Kuttey, after all, is a student project disguised as a film.

Premium

Premium