India's 'Into The Wild' Story: Travellers, Drawn To 'Death Valley', Mysteriously Disappear

Parvati Valley and the hills around Kullu-Manali in Himachal Pradesh have registered at least 21 disappearances of foreign nationals over the past three decades. What was common to these travellers and Chris McCandless, the subject of 'Into The Wild', was an elusive — maybe even timeless — quest.

Poster for Into The Wild, a photograph of the Parvati Valley, and a Facebook picture of Justin Alexander Shetler

Last Updated: 02.34 PM, Oct 03, 2022

Part I.

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived... I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life...”

Since the time Henry David Thoreau wrote those words in Walden, published in 1854, generations of travellers have been influenced by the philosophy he espoused. Walden outlined Thoreau's thoughts and experiences from a two-year stay in a secluded log cabin by Walden Pond in Massachusetts. While it is disputed just how isolated and devoid of the trappings of modern civilisation Thoreau's cabin was, what isn't, is that his words have triggered a desire to "live deliberately" in many of his readers' minds.

Among these readers was Chris McCandless, the famous subject of a 1996 biography titled Into The Wild by the writer Jon Krakauer. McCandless was 24 when he died, in August of 1992. A movie adaptation of Into The Wild was directed by Sean Penn, and released on 21 September 2007. This week was the movie's 15th anniversary. McCandless would have been 54 if he had made it out of the Alaskan wilderness, where he spent his last few months living off the land, cut off from any contact with the outside world.

From Thoreau to the naturalist John Muir to environmentalists like Edward Abbey and travellers like Christopher McCandless, there's perhaps a line that can be drawn: individuals who wanted to discover their true selves, the one that was not formed of the "artifice of mirrors" as Tennessee Williams might say. The self that could be discovered only in solitude and shorn of the constructs imposed on it by society and their place in it.

Extend that line further, and you will reach Justin Alexander Shetler.

Towards the end of August or early September 2016, Shetler, a survivalist and travel influencer in his mid-30s who revelled in pursuing the "road less travelled", went missing in India's Parvati Valley. Shetler was last seen on August 22 that year, when he told a Russian traveller that he intended to undertake a three-day trek to Mantalai Lake. September 2022 marks the sixth year since his disappearance.

As uncommon as his life may have been, Shetler's disappearance, unfortunately, wasn't. At least not in Parvati Valley, where up to 21 foreign nationals have vanished over the past three decades. This is just the number of disappearances — not deaths, of both Indian and foreign travellers, in the same span. The latter toll is high enough that this picturesque region in Himachal Pradesh's Kullu District (which includes the towns of Kasol, Malana — names that are familiar as much for their outdoorsy delights as for the intoxicating substances found in abundance here — and Manikaran) has been given the moniker of "Death Valley".

***

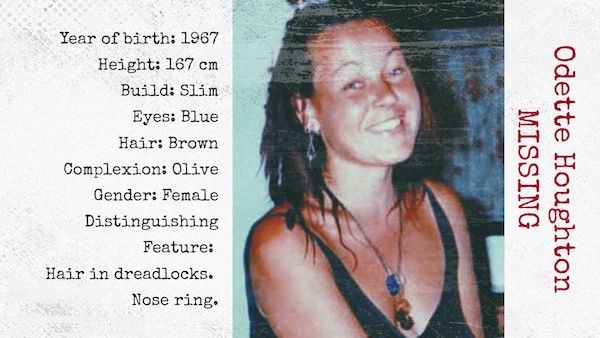

In April of 1990, Edward and Marie Houghton celebrated their 25th wedding anniversary with a family vacation in Thailand. Their 23-year-old daughter Odette had been living in India at the time, but joined them on the trip. The young woman, then wearing her hair in dreadlocks and sporting a nose ring, was known by her parents to be a free spirit, keen on seeing the world. “India is incredible,” she announced to everyone she met. By August of 1991, Odette was untraceable, last seen in the hills of Kullu-Manali. The Australian Federal Police’s Missing Persons board still lists her as “missing’, three decades later.

The hills around Kullu-Manali are many things to many people. Every summer, they boil over with noisy domestic tourists frantically trying to abscond to the chilly climes that are an antidote to the rest of India. To a small minority, this is also where you can locate easy drugs, an off-the-grid lifestyle, and (depending on the kind of people you run into) some amount of vice. Ganja, charas and more recently chitta have, like snow, settled into the many unmonitored crevices of the hills. It’s almost as if the very shade the valley provides from the Indian summer has also enabled its social decomposition. This was Odette Houghton’s last known location.

Edward Houghton travelled to India to discover what had happened to his daughter. After approaching the local police and Interpol for help, and putting up posters of Odette all over the valley, he returned home to Australia.

***

Odette’s disappearance happened in a pre-internet era, but this was also when India was opening up to the rest of the world financially. A telecommunication revolution connected the far-flung limbs of this vast country. In unlocking India to the world, globalisation exposed certain untouched geographies and a sense of constitution they had inherited, to a new phenomenon — the influx of the foreign traveller. Some of Himachal’s remote regions, now regarded as popular tourism destinations, are also places that have taken the longest to arrive into the modern age. They have resisted change, the arrival of alien cultures, and the abrogation of an indigenous way of life in the service of the outsider. Even if the opportunity presented itself, it has been hesitatingly accepted. Naturally, with unfamiliar opportunity comes unanticipated conflict.

In 2000, a German backpacker was shot and killed while sleeping inside his tent. A month later a camping Spanish family was beaten to death, with only the father managing to flee. Violence can never really be predetermined, but given the rise of technology it can at least be documented. The pre-digital/pre-internet era made the human footprint incredibly difficult to track. Technology’s evolution, its intrusive presence in our lives, should have ideally prevented people from vanishing in the same neck of the woods where so many others had gone missing. But it didn’t.

***

When Justin Alexander Shetler was lost to the topography of the Parvati Valley, it was the latest iteration of a story that has so many moving parts, it probably cannot be woven into a singular narrative. Shetler’s disappearance, however, did stand out for a couple of reasons: he went missing in the social media era and was a prolific presence on these platforms. It’s what intrigued Canadian journalist Harley Rustad to delve into Shetler’s story.

“I quickly realised that Justin had such an incredible life story, a profoundly tragic history, that raised a number of very current issues: the push and pull of social media, the endless search for illumination, the restlessness to understand our place in the world, and the extremes we take to find meaning in life. The more I dug into Justin’s backstory the more I realised that his was a life that spoke to many people, both in their struggles and in their desires and questions,” says Rustad, whose Lost in the Valley of Death: A Story of Obsession and Danger in the Himalayas was published in January 2022.

Rustad followed the trail of the many, many disappearances in the Parvati Valley, but he was clear that he wanted to focus on unravelling the path of just one: Shetler. “His life spoke to so many of these complicated and complex elements that ultimately made such a rich story, and touched on a spectrum of issues including the lure of India as a spiritual destination, working through personal trauma, drugs, local police investigations, and the history of tourists dropping off the map to live long-term in India, to name just a few,” the author explains.

And of course, Shetler’s journey right until he went missing was about a quest that all of us are on, albeit in wildly different ways: the one for finding meaning.

In Part II, we continue the story of Death Valley.