Amid Justice Hema Report Row, Assessing Malayalam Films' Misogynistic Playbook

Amid the Hema Committee Report revelations, it is time to call out Malayalam cinema's tendency to platform narratives that normalise and trivialise sexual harassment, writes Neelima Menon.

Last Updated: 04.50 PM, Aug 29, 2024

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on August 29, 2024. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

THE MALAYALAM FILM INDUSTRY is in the eye of an ugly storm, following the release of the Justice Hema Committee report on August 19. The (redacted in parts) report details a troubling pattern of harassment faced by female members of the industry.

The Committee was among the measures that arose out of the 2017 arrest of actor Dileep, for allegedly conspiring to abduct and assault a female colleague. The incident starkly underscored the unsafe working conditions, predatory workforce and exploitative culture rampant in the Malayalam film industry. It also led to the formation of the Women in Cinema Collective (WCC), comprising female artists and technicians who wished to bring social awareness and implement better working conditions and opportunities in Malayalam cinema. Then came the Justice Hema Committee, set up by the state government. The Committee shared its report with the government back in 2019, detailing the pitiable working conditions of women in cinema, including the pervasiveness of sexual harassment, poor pay and lack of basic facilities.

It is after a delay of five years that the same report has now been released to the public, horrifying audiences with accounts of commonplace sexual harassment. While all this has been unfolding off screen, on screen too there is a clear tendency to platform narratives that have normalised and trivialised sexual harassment.

For instance, in his debut film Kasaba (2016), Nithin Renji Panicker regrettably follows in his father, the popular screenwriter/actor/director Renji Panicker’s footsteps, objectifying women on screen. Not only is Kasaba’s SI Rajan Skaria (Mammootty) portrayed as a virile womaniser, but the glorification of his sexual prowess perpetuates toxic masculinity. Right from the first scene, Skaria’s attempts to remain “cool” are rooted in his questionable reputation as a “ladies’ man”. So when a female colleague is shown gawking at Skaria, another colleague provides gratuitous commentary on his sex appeal. It reduces the female cop to a stereotypical and demeaning figure. When the female cop, who has her shirt slightly unbuttoned, confronts Sakaria for not saluting her, he obliges — then casually pulls down her pants while passing a lewd comment. More concerning is the way in which the scene is staged, with a triumphant and playful background score that endorses Sakaria’s sexual misconduct.

In the ‘90s, Nithin’s father Ranji Panicker created alpha male heroes who revelled in bullying strong-willed female leads and reducing them into meek, apologetic figures. One of the earliest fatalists remained Sub-Collector Anura Mukharji (Vani Viswanath) in The King (1995; directed by Shaji Kailas) who receives a patronising tongue-lashing from her senior, Joseph Alex (Mammootty) for not obeying his orders. Not only is Anura made to feel remorseful, but she subsequently consents to his honey trap scheme, and there are also hints of romantic feelings towards him. How conveniently the narrative downplays the senior’s condescending behaviour and reinforces harmful power dynamics!

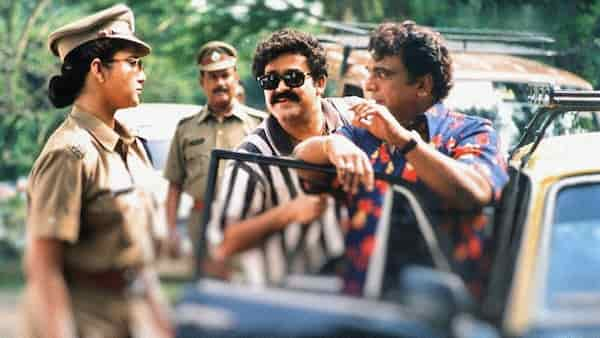

Perhaps Nithin also found inspiration from Joshiy’s Praja (2001), once again written by his father, which features a disturbing scene where Mohanlal’s Zakeer Hussain molests a female cop in public. It’s further worsened by the inaction of her subordinates when he pushes her against his car and tells her to zip her pants (all while spouting sexually explicit comments). This is yet another disturbing instance of trivialising sexual harassment as well as toxic behaviour.

Meanwhile, we have Joshiy’s Run Baby Run (2012) with a broadcast journalist (Mohanlal) as the protagonist. He uses his position to get back at his girlfriend (Amala Paul) after their sour break up. He is disrespectful and verbally abuses her — yet, the narrative chooses to play down his harassment.

In Lal Jose’s Meesha Madhavan (2002; starring Dileep and Kavya Madhavan), when the hero breaks into the heroine’s room to steal her hip chain, he mumbles while staring at her sleeping figure: “I feel like r*ping her.” Talk about trivialising rape in the guise of humour. Mr Marumakan (2012) goes a step further and normalises rape. When he realises that his sister might be a victim of rape, he decides to swap her for the villain’s sibling and laughs heartily after the cruelty is executed.

In Ente Upasana (1984; dir. Bharathan), when Lathika (Suhasini) is raped by a friend’s brother, her distressed mother dies by suicide, and her fiancé abandons her. Left to fend for herself and her child, Lathika somehow manages to rebuild her life — only to come face-to-face with her predator (Mammootty) at her workplace. Her predator, determined to win her back, harasses her at work. His blatant interest in Lathika leads to office gossip, which further traumatises her. Typically though, the narrative is too focused on the predator’s redemption and elects to romanticise their encounters. Lathika ends up marrying her rapist.

In Joshiy’s Kuttettan (1990) not only is the hero’s playboy image depicted as a fun trait, but also, the narrative shrugs off adultery and workplace harassment. His interactions with women across age groups are deemed “cute” when really they’re red flags. This includes his sly attempts to flirt with his office staff. Throughout the narrative, however, he is never held to account for his predatory nature.

Priyadarshan’s Vandanam (1988) romanticises harassment and stalking by portraying the hero’s (Mohanlal) invasive behaviour as love, disregarding the heroine’s (Girija) consent and autonomy. When he pursues the convict’s daughter under the guise of investigation, the narrative glorifies his actions of invading her privacy, stalking her and forcing her into a relationship. The proposal scene, in particular, crosses the line into harassment but is framed as a romantic gesture; to date, it is a constant feature on social media to express unrestrained love.

In Rajeev Ravi’s Annayum Rasoolum (2013), a localised adaptation of Romeo & Juliet, the love story between Rasool (Fahadh Faasil) and Anna (Andrea Jeremiah) develops with the former relentlessly stalking the latter. From following Anna on her way to work to snooping on her from her neighbourhood at night, it’s a disturbing stretch. Perhaps it is Fahadh’s genteel real-life image that led to the sanitised view of his character’s actions, glossing over the problematic aspects.

If there is one movie that offers a candid and unflinching portrayal of the Malayalam film industry’s dark underbelly, specifically the sexual abuse, power imbalance and gender bias that pervades it, then it is KG George’s Lekhayude Maranam Oru Flashback (1983). The narrative traces a young actor’s journey to stardom, yet sensitively showcases how even at the pinnacle of her success she remains trapped by the system of exploitation and patriarchy. The film's core plotline is eerily echoed in the Hema Committee report, underscoring KG George's intuition and nerve in tackling these issues long before they became mainstream concerns.

Premium

Premium