Fairly Folk: A Wonderfully Weird Film On Marriage & Stability

Director Karan Gour takes a playful premise and layers it with magic realism, crafting in the process astute observations about life, gender politics and love

Last Updated: 07.50 PM, Mar 01, 2024

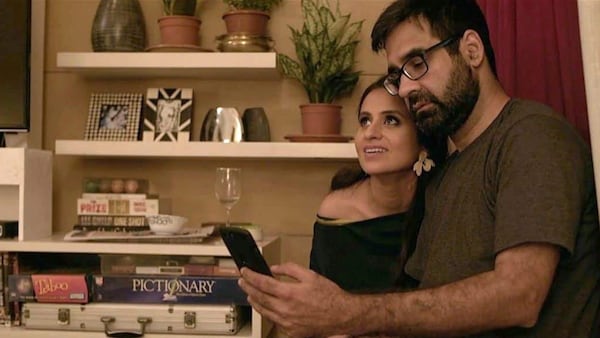

IN Karan Gour’s Fairy Folk, solutions arrive out of nowhere. When a married couple’s car breaks down in the middle of a forest, they encounter a strange, mythical being. The people in question, Mohit and Ritika (Mukul Chadda and Rasika Dugal — both terrific and fearful in how terrific they are), are scared out of their wits but when they make a dash for home, the creature, a literal fairy folk, follows them too. This sudden disturbance transforms into a timely intervention as the new entrant catalyses a tale of belated desire and potential promise.

Gour takes this playful premise and layers it with magic realism, crafting in the process astute observations about life, gender politics and love. On paper it might seem like a tall task but Fairy Folk unfolds as an instance of assured filmmaking where the subtext never overwhelms the context. It is an experimental outing that remains attuned to the demands of relationships and the pitfalls of marriage, and during its runtime, lays everything bare without sharpening its gaze for a stringent critique.

Fairy Folk reminded me of a film I had watched at a film festival years back and one I keep thinking about: Mragendra Singh’s Normal. The remarkability in Singh’s work resided not in striking image-making but in the emotional acuity it was addressing. Normal centred on an interracial married couple whose sex life is hampered once they have a kid. The problem is evident and so is the upshot. But the film insists that the issue is deep-rooted and hardly noticeable to the naked eye. For the people in the arrangement, the domestic stability had lulled them (they are always nice to each other, too polite to start a fight) to a platonic routine that felt impossible to disrupt. Normal culminates with the couple manufacturing a friction to challenge normalcy, and thereby dismantles a narrative that suggests that all relationships aspire for a silence-sharing and snore-tolerating stability. Gour’s film is the weirder cousin that gives yearning the centre stage.

Once Mohit and Ritika get used to the presence of the fairy folk, it is the home-staying man who gets more invested. Ritika, the breadwinner of the family, hardly has time. Mohit has plenty. So, he figures out a way to dish out orders. He paints eyebrows on the genderless being, trains it to follow his voice. In a perverse way, he imagines himself to be someone like Victor Frankenstein and forges a master-slave dynamic with the being. Except he is more benign, or so he thinks. At a houseparty when he showcases his creation to his stunned friends, Mohit pulls down the fairy folk’s pants to reveal that it is gender less. When one of his drunk friends tries reenacting this intrusive act, Mohit calls her out for crossing a line.

But the individual project evokes collective curiosity when during a night of drunken fervour, Mohit kisses the fairy folk. The act of affection transforms the being as it imbibes the attributes of the person it was closest to: Mohit. The fairy folk becomes a man— they name him Kabir (essayed by actor Chandrachoor Rai) — who is a strange combination of the past and the future. He is who Mohit was (more well-built) and who Mohit could not be ( more adventurous). Kabir is the literal manifestation of the “friction” that the couple in Normal had created. And much like in Singh’s film, the two principal characters in Gour’s outing recognise the importance of it.

We do not see it but it is not difficult to imagine that Mohit and Ritika’s marriage had hit a comfortable road(block). They have friends who drop by at their home. Evidence of their inner lives without each other is scant. The presence of Kabir creates a curious threesome that they clutch on to, to revive their marriage. Thus, Ritika starts sleeping with Kabir and the newness of it reminds her of the heady honeymoon phase that has all but died down with time. Mohit, the dejected man and a bystander in his own house , tries doing something similar. He goes back to the forest (the expansive Aarey in Mumbai) to find another fairy folk. Once found, the process is repeated and sealed with a peck by Ritika.

But here’s the catch. The next morning, as Mohit hurries to freshen up, he meets Hamza (Asmit Pathare), a woman trapped in a man’s body. She has inherited feelings for him but Hamza is not who Mohit wants. He feels defeated but they both form a bond. Hamza’s interstitial identity also helps Mohit open up. For instance when he takes Hamza to his boys’ poker night as a cousin, he behaves differently. He no longer carries the male burden to be performative to impress. Instead, he and his other male friends behave like most men do when no one is watching: like kids. Hamza needles them with cuss words, delighted to see how little it takes to be a delight. It is a standout moment and Pathare is tremendous, emoting with his eyes even as his tongue speaks a different tongue.

Although it is easy to be taken by how weirdly wonderful Fairy Folk is, it is impossible to not see its emotional clarity. The film unravels as improvisation even in the most taxing scenes and uses realism both as narrative language and ambition. Gour refuses to settle for less (evident in the way he casts a real-life married life) and raises fundamental questions about love, companionship and marriage. Unlike Ritika, who enjoys being with Kabir and feeling the way she used to years back, Mohit, the de facto protagonist, is left wanting. He develops a bond with Hamza and yet he is convinced this is not what he wants. Fairy Folk goes the extra mile to investigate — for both the characters’ sake and ours — what we want from the other person in a relationship: is it to remember how they made us feel or is it to not forget how we can make someone feel? Is it because of the person we become with them or is it because of the person we can make them be? Is it physical or psychological — generous or self-serving?

Fairy Folk provides no easy answers simply because there are none. But it is a rare film that willingly ruptures a functional relationship to probe the undersides. It is a brave outing that does not hold back from outlining a scary prospect that functionality in marriage is both the end goal and the undoing. It is what awaits us and where we wait to arrive. It is also a state of constant yearning, like an aimless walk into the forest in the hope of encountering a fairy folk.

Premium

Premium