Dil Chahta Hai & The Love-Is-Friendship Syndrome

This is #ViewingRoom, a column by OTTplay's critic Rahul Desai, on the intersections of pop culture and life. Here: Notes on Dil Chahta Hai.

Last Updated: 03.37 PM, Sep 24, 2023

MY partner is my best friend. I know this sounds aspirational and ideal and all sorts of sweet. It’s true that we’re disturbingly comfortable with each other. And it’s nice to be lulled into a safe space – to finish one another’s sentences, make politically incorrect jokes, burp freely, laugh like hyenas, or magically find each other’s arms in crowded bars. She follows me around a room where we know nobody; I sit next to her in a room where we know everybody.

But it’s also complicated. The sibling vibe often blunts the romantic edge; the soul stifles the body. Our fights emerge from the frustration of being too cosy – of projecting the platonic pressures of friendship onto the sexual tensions of togetherness. It’s too easy to cross over from teasing-your-lover territory to kissing-your-friend territory. This isn’t an unfamiliar problem for long-term couples. Compatibility and chemistry become mutually exclusive. But I’m aware that, in my case, there’s a complex or two at play.

A lot of it is rooted in my misguided habit of treating love as the lost-and-found section of a station where trains keep departing. I view a romantic relationship as a shape-shifting bond, something that can conveniently expand to protect bits and pieces of baggage we leave behind. If I lose something or someone, my reaction is to find solace in the elasticity of love; I see my partner as someone who can not just be but replace. I often seek in her – and us – what I lack elsewhere. As it turns out, this elsewhere-lacking increases with age: Families fade, dreams dim, the future lessens, and most of all, friends drift. So my relationship is forced to bear the brunt of my social isolation, the progressive disillusionment with a life that keeps getting smaller. I expect her to be my childhood friend, college buddy, colleague, writing mate, travel twin, shoulder to cry on, gossip pal, drinking partner and midnight texter at once. Again, it sounds cute, but it’s unfair and crippling. It reduces the idea of companionship to the concept of company.

This plural sense of attachment has driven away girlfriends before. I can’t blame them. My first instinct, always, is to renegotiate my troubled history with human attachment. My reasoning is that if I make new friends – or perhaps make peace with the grammar of friendships – my partner might be freed from the burden of playing multiple roles. But it’s been an uphill battle. It’s a condition that’s hard to reverse. I trace it back to my formative years. As the only child of parents who battled through a marriage of excesses, the early connections I made were steeped in dependence and escapism. They weren’t just other kids to hang out or play cricket with; they were my parachutes of sanity. I craved not for people so much as entire lives and families. I straightaway went for boom or bust – brotherhood or nothing – in my pursuit of both profound meaning and Jurassic-Park-like adventures.

Small-talk never appealed to me. I liked personal equations, even if it meant not subscribing to groups and party culture. I thrived on one-on-one exchanges, a trait that was treated with suspicion by elders who equated popularity with success. Walking around a garden and “chatting” about life wasn’t exactly everyone’s 12-year-old cup of tea. As an adult, not much changed. The size of those gardens got bigger. But a pattern emerged. Many of these friendships imploded the moment we grew too close. The second we put ourselves in a position to expect more – and therefore feel grateful or let down – the pressure triggered a fallout. Feuds were rooted in the frictions (and fictions) of proximity. It’s almost like men can’t handle the intensity of being too important – or too present – in each other’s lives. After the implosion, these bonds would continue, but as diminished versions. I’d then be at a loss of how to approach a casual or detached friendship, one where I’m not supposed to feel bad about cancelled plans or a general lack of commitment.

It still happens, well into my thirties. The transactional nature of modern attachment means that the act of having a good friend implies the responsibility of being a great friend. I’ve seen old friends deliberately drift and back away – and basically be lesser people – so that they aren’t expected to offer loyalty and support in return. (“If we maintain superficial exchanges, we earn the right to be superficial ourselves”). It’s like the situationship version of friendships, where adults calibrate their actions according to how obligated or invested they want to feel. This was an especially tricky space to navigate during the pandemic, when the selfish ones hesitated to ask for help because they were incapable of returning the favour. They didn’t want to adopt the pressure of being selfless people. I realised that, at times, the only way to be on peaceful terms with someone is to maintain a careful distance – the lesser the contact, the lesser the (chances of) erosion. That distance doesn’t come naturally to me.

Then there are some who are overenthusiastic givers only so that they can respect themselves and show the world that they’re solid friends. A former-journalist friend let me sleep on his couch during a tough phase only to flaunt a balance sheet of the courtesies I hadn’t ‘returned’ over the years. He lashed out the minute it got too real and vulnerable for him, because he was already using me to atone for manipulating a sensible partner. The result: We went from brothers to bitter strangers in minutes. He kicked me while I was down – while I was grieving a huge loss – because I trusted in his performative empathy and gave him the power to heal me. The power made him panic.

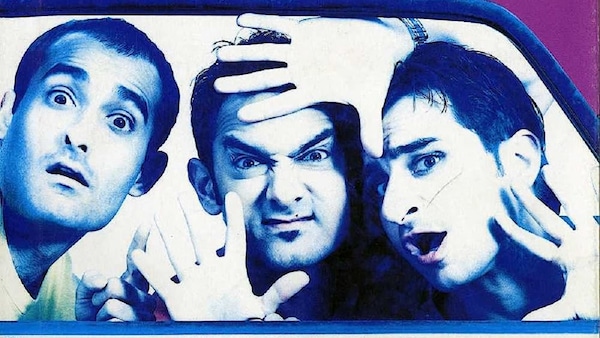

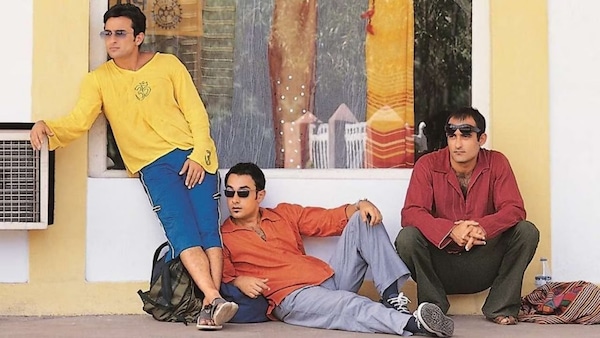

Either way, my struggle to find a resting ground – a midpoint between acute and passive – has been long and eventful. I have an idealistic reading of friendship, one where people don’t just meet but form lasting impressions on each other. It’s not just about socialising and having a good time; it’s about making a dent in time. And this disillusionment of flying too close to other suns has spilled into – and shaped – my love stories. Every time I watch the definitive buddy movie of my generation, Dil Chahta Hai, I interpret it differently. It’s no coincidence that the three inseparable college friends only grow up after parting ways with each other.

Each of them falls in love, but there’s a distinct sense that they’re filling the void previously occupied by friendship. Their relationships are emotional rebounds of sorts: They seek company before it morphs into companionship. Akash is pleased to see Shalini lapping up the sense of humour and rakishness that used to tickle Sameer and Sid. It’s who he is; in the beginning, she’s a surrogate for his absent pals. Sid spends his weeks with someone mature enough to accept his old-soulness and intellectual gravity. Sameer finds a girl who sees him as more than just the middle-friend and jester in a trifecta. These romantic partnerships are yearnings for new equations with old feelings.

A few years ago, I’d have said that friendship was holding them back from finding their soulmates and careers. It kept them satisfied and busy and happy, so they didn’t feel the urge to look for anything beyond each other. And they evolved the moment they moved on. But now I believe that, in a practical universe, the three of them never truly patch up. Sure, they apologise to each other and have picnics together with their spouses in the end credits. But I think they also struggle to adapt to newer, grown-up identities. Akash probably wonders why Shalini doesn’t enjoy impromptu Goa trips; Sameer probably wants Pooja to drink with him at quarter bars; Sid probably expects his girlfriend to rush to his house in the middle of the night to admire a new painting. Every time Akash ditches a dinner, Sameer or Sid try to sculpt their date nights into cooler versions of that plan. In the process, their private lives struggle to unfold on their own terms.

Perhaps one of the reasons some people disappear after marriage is because they’re shielding their love from (being defined by) the disappointments and limitations of other bonds. The simple explanation is that there’s no time; the honeymoon phase is exciting; friends can wait. But maybe they also want to save themselves from wanting their relationship to be more. They’re preserving the singularity of attraction. If friends cease to exist altogether, there’s no question of turning love into a compensatory all-in-one package. If Akash, Sid and Sameer cut each other off fully, at some point they will start making new memories unvarnished by older ones. They will stop missing and start moving. Their partners will have no other shoes to fill. But it’s also unhealthy – to reduce one’s heart to a ‘choice’ between social dimensions. It risks a different kind of resentment, one that stems from a lack of emotional flexibility.

I don’t know if there’s a solution. As an introvert, so many of my problems emerge from the need to belong. I looked for familyhood in a broken home, home in unsuspecting friends, and friendship in resilient lovers. It’s like directing a low-budget film in which nobody ends up playing their original parts. Everyone is supposed to do a little of everything else. The job profiles become too fluid and exacting; they forget their real identities. The film keeps faltering, the crews keep quitting, and I continue to reframe my own culpability on the road to nowhere. But my partner stays. She tries to puncture the chaos. Every now and then, we go to watch a show of this film. It’s a late-night date. She knows the lines by heart. We complete each other’s laughter and tears. I watch her eat the cheese popcorn. She watches me get (too) cosy in my jacket. Our arms brush. We think of what is; we imagine what could have been. When the lights come back on, we silently head for the exit. And we walk out as soulmates pretending to be best friends.

Premium

Premium