David Lynch, The Last Dreamcatcher

Lynch's movies bristled with magic realism, personal impulse and dreamy abstractions; they had a primal desire to turn cinema into a medium that needed to be felt rather than fathomed.

Lynch spoke like a man with nothing to lose: unfiltered (like his cigarettes), unperturbed, undone, without any inherent instinct for self-preservation.

Last Updated: 04.33 PM, Jan 19, 2025

MOST PEOPLE REMEMBER exactly where they were — not just the place, but the language of time itself — when they first watched the movies that changed their lives. I was a 20-year-old kid in my bedroom, waiting for a phone call from a college friend, when I decided to watch Amadeus on my laptop; the rest (including the friend) was history. I’d eaten a chilli cheese toast for breakfast when our film school professor quickly projected Amelie onto the screen — but only an hour of the film — before the next lecture. I watched Before Sunrise on a DVD at dawn to impress a girl I liked. I saw Inception with a couple, at a packed suburban multiplex on a rainy evening, a day after breaking up with the girl I had once impressed. I saw Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi alone, as a silent tribute to my dad in rehab, breaking the tradition of catching every new SRK release together.

But I don’t quite remember where I was — or even who I was — when I first sat through The Elephant Man. Ditto for Wild at Heart (which I no doubt chose for Nicolas Cage) and Eraserhead (which I’m sure I watched in my late twenties). I know I was studying cinema when Mulholland Drive was shown to us, but I can’t recall the precise day, the before-and-after vibe or the people around me. In fact, I don’t remember coming out of any David Lynch film thinking: damn, my life will never be the same again. For the most part, I was just wondering what I was seeing and how it existed. It was more like: hey, is that allowed? Wait, what happened? Whenever someone used the term “Lynchian” in a live conversation, I’d mentally label them as a pretentious cinephile. It felt like a shapeless word that people used to flaunt their intellect. It also felt like an all-in-one adjective that allowed people to sound confident without having to admit they didn’t understand a thing.

I did enjoy reading and watching his interviews, though. He sounded like an alien who was put on this planet solely to make art. Everything else — including social existence, breathing, eating, dealing with humans, living — felt like awkward add-on packages. They were the equivalent of waiting between shots. The oddball personality was a consequence of operating outside his realm of purpose. It was a result of being out of width, not depth. It was like watching an athlete off the field but always in his jersey, trying to figure out how to go about the non-sports parts of life. It’s why he spoke like a man with nothing to lose: unfiltered (like his cigarettes), unperturbed, undone, without any inherent instinct for self-preservation.

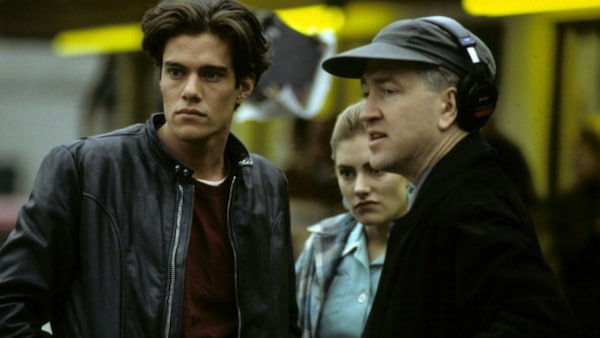

I liked imagining his day-to-day interactions and mundane moments, even as he tweeted about birds and offered unique weather updates from his home. I would search for clips of him directing on set — scolding his producer for a ‘commercial’ remark or applauding his actress like a proud dad. Seeing him smile was surprising; it was like seeing a dog fly; he was simply not designed to do that. I also kept going back to Roger Ebert’s review of Mulholland Drive to learn how to write about movies that made me feel silly and wonky. Not small, mind you, just silly. The piece internalised the distinction by going beyond film criticism. But I’d be lying if I said I rewatched any of Lynch’s movies — or even his television (Twin Peaks) for that matter. It was once and done. Barely dwelled. There were no extreme, visceral reactions. It was always like encountering a new creature that made you curious instead of blowing your mind away.

But as the years passed, I started to recognise that Lynch’s work didn’t alter lives like a stormy romance, it shaped lives like an intangible companionship. Its influence is silent, permanent, almost invisible to the naked heart — a bit like Great Expectations’ Arthur Lustig, the mesmerising convict who appeared in Finn’s childhood and became his future benefactor without him realising it. Just as Lustig quietly sculpted Finn’s art career in return for an act of kindness, Lynch’s filmmaking quietly sculpted my career in the arts in return for an act of engagement. I didn’t realise it, but his movies — bristling with magic realism, personal impulse, dreamy abstractions, and a primal desire to turn cinema into a medium that needed to be felt rather than fathomed — had expanded my idea of expression. Form was no longer a constraint. The narratives didn’t make sense because they turned storytelling itself into a sixth sense: the sense of thinking as creating. They weren’t memorable because they projected the very essence of memory. I couldn’t recall where I was during these movies because I was too busy experiencing them instead of admiring or connecting to them.

When I started to write about film, I didn’t care much about whether my sentences amounted to something. Or even whether my musings were complete. I still don’t. Sometimes, I have no idea what I’m trying to say. I’ve no clue why I’m putting certain words together. Sometimes, they just sound good; other times, they look incomprehensible and weird. But in some absurd way, how others perceive these words — differently, indifferently, vulnerably, emotionally or dismissively — attaches deep meaning to them. Cognisance isn’t as important as conjecture. It’s not a stream of consciousness so much as a choppy ocean of it. It widens the democracy of how art can be consumed: you can watch literature, taste music, hear paintings, smell architecture and touch stories.

This very much speaks to the kind of subconscious ambition that someone as unalloyed as Lynch instils in us. It’s not as simple as saying that he invented a new vocabulary of moviemaking. What he really did was make it possible to process cinema on our own terms. In our own vocabulary, in our own space and time. He somehow liberated the medium from both convention and pretension — empowering generations of latent dreamers to deconstruct cinema into tiny bursts of inner reasoning. It’s a lovely legacy to have and, given the Netflix-ication and Marvel-isation of modern film, an immortal one to leave behind. Perhaps that’s what “Lynchian” really is: not a reductive adjective or word so much as a genre of sensory truth. It’s the casual courage to transcend acceptance and, at some level, be the most imperfect version of perfection. Being Lynchian goes beyond the screen, of course, and it involves the agency to not settle on any single sentiment.

Perhaps it’s only fitting that I can’t quite remember where I was when I heard of David Lynch’s death. It didn’t immediately affect me. It wasn't a shock, but maybe a kind of inconspicuous sadness of missing something we’re built to take for granted: like being a child, or going to school, or waiting for a parent, or falling in love. As I write this, the magnitude of his absence is only now beginning to reveal itself. It won’t alter the path of cinema so much as shape the afterlife of it. The void will, I suspect, provoke the sort of longing that gets exposed every time we are at a loss for words, logic, wonder and wastefulness. And every time we are the loss itself. We might search for sense and gratification without even realising it. This grief is, after all, very Lynchian.