Call Me Bae: Ananya Panday Shines In A Show That Takes Time To Come Into Its Own

Call Me Bae tries too hard for too long. It is not just the broad references it borrows along the way but even as a stand-alone entity, the series struggles to recognise what it wants it to be.

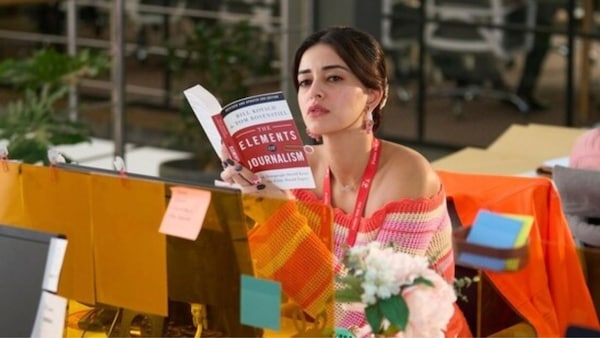

Promo poster for Call Me Bae.

Last Updated: 02.10 PM, Sep 06, 2024

DHARMA HAS A NOSTALGIA PROBLEM. The production house keeps looking ahead by looking back and uses films, made by them in the past, as subtext and context for the films they are making now. The hat tips are so persistent and plenty that they have become a crutch for tedious writing. A telling example is Anand Tiwari’s Bad Newz (2024), a slapstick that collapsed once forced to show up for itself after hiding behind sentimentality. Call Me Bae, the new series from the banner leans close to this practice. Centring on a poor little rich girl forced to navigate the real world once pressing circumstances arise, the premise is cut out for Dharma, a production house that treats the middle class as a conspiracy theory even on good days.

The problem, again, is of plenty. Written by Ishita Moitra, Samina Motlekar and Rohit Nair, Call Me Bae feels too many things at once. The first couple of episodes (there are eight) are packed with self-reference, and then comes the other influence. The basic setting is familiar to the American sitcom 2 Broke Girls; the protagonist's character arc is too Legally Blonde, which in a way got an update with Schitt's Creek, the beloved Canadian show, through the character Alexis Rose. Call Me Bae unfolds carrying bits of all these outings even as it continues doffing its hat to characters from Hindi films, causing a tonal bottleneck that takes time to fall into place.

Bae aka Bella Chowdhury (Panday) was born with a golden spoon. Her parents are socialites in Delhi and her father only wanted a good-looking family. Once their family business starts making losses, her wedding with Agastya (Vihaan Samat), a rich heir to another rich family in the city, is arranged. Their marriage is perfect. They have helpers more than family members, she flies to Milan on the weekends for shopping and has chefs from different parts of the world to arrange her breakfast. But Agastya has no time and Bella feels alone. Her bags (each with a name not unlike Moira Rose from Schitt's Creek naming her wigs) are her confidantes till she meets a dreamy gym instructor, Prince (Varun Sood) and an affair is on the charts. They are caught unceremoniously, marking an end to her marriage, her socialite career and her lifestyle.

Directed by Colin D'Cunha, Call Me Bae tries too hard for too long. It is not just the broad references it borrows along the way but even as a stand-alone entity, the series struggles to recognise what it wants it to be. Does it want to be a fun coming-of-age story about a socialite-turned-hustler in Emily in Paris couture? Or, does it want to be a story about sisterhood? Or, is it a satire on modern-day journalism? The latter feels incredulous because it has become such a beast that no amount of lampooning feels enough.

The jokes come from all quarters. In a flashback voiceover, Bae says, “The only plan I was allowed to make was a diet plan”, when she rides an auto for the first time, she compares it to Mini Coopers without doors. When she sees white bread in Mumbai, she shrieks. Bae thought they were eradicated, like polio. The gags are not unfunny but predictable, more so for Moitra, who has a discernible style, evident in Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani and Bad Newz – the last two films she was a co-writer on.

It is only when Call Me Bae embraces its frivolity and resists aping others that it truly comes to its own. This is not to say the series metamorphoses into something else but that it becomes more fun, engaging and assumes a clarity missing earlier. The logical loopholes remain, like a Vietnam-style hostel existing in Bandra, Bae getting a job in a media channel after her video of being drunk and lambasting one of its star journalists, Satyajit Sen goes viral, or connecting the main plot to a larger #MeToo narrative only for it to settle in easy three steps. But if they become easier to overlook after a while it is because Call Me Bae reveals itself to be committed to the ride and not the journey. It becomes clear that the show is dedicated to making sweeping statements and easy solutions. It wants to skate on the surface.

In that sense, the series owes its biggest debt to Panday who steps into the world, aware that she is the punchbag of most of the jokes. The impressive thing here is that her consciousness never heightens into wanting to overdo it. She is constantly watchable, effortlessly straddling her character references and imbuing Bae with something distinctly her own. In more ways than one, the show rests on her shoulders and she wears that responsibility lightly but not with triviality, managing a balancing act that is difficult to achieve. Enabling her are another set of persuasive actors, like Gurfateh Pirzada as Neel, the ‘serious’ journalist whose show gets no TRP, Muskkaan Jaferi as Saira Ali, Bae’s betting-addicted friend who introduces her to sis-code and Niharika Dutt as Tammarrah, her go-getter flatmate. But it is Vir Das who is crackling as a manic, TRP-hungry Bengali journalist who forces his parents to eat rice with a fork. His character is an iteration of a journalist whose histrionics have been iterated in several outings but Das humanizes Satyajit Sen with a Miranda Priestly vibe.

Call Me Bae is one of those distinct series that veer more towards good than bad. The characters take time to come into their own which will pay off once the show becomes — and it will be — a franchise. Bae might fill in the Poo-shaped pop culture hole but the show should have been ambitious. It should have located its own possibilities instead of looking elsewhere because its potential was marred by its own decision to be complacent.

Call Me Bae is currently streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

Premium

Premium