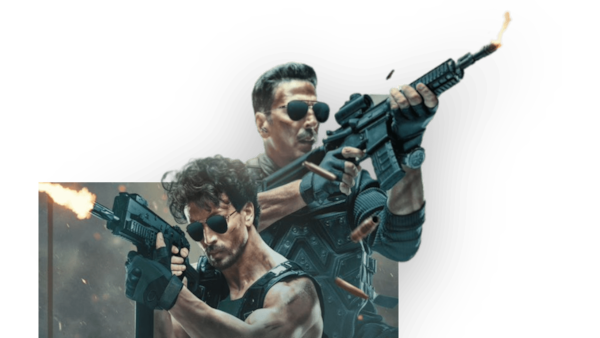

Bade Miyan Chote Miyan: A Bicep-Flexing Showcase For Akshay Kumar & Tiger Shroff

The problem with Bade Miyan Chote Miyan is that it is a feature film when it could have just as well been a Reel — and not even the most engaging one out there

Last Updated: 01.48 PM, Apr 11, 2024

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on April 11, 2024. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

IF I HAD A PENNY for every time a Hindi film claimed that India was caught in a near-catastrophic crisis only for it to be resolved in 20 minutes by men who frankly seem incapable of doing much, I would have made a lot of money. But even this financial windfall wouldn’t compare to what has been spent on Ali Abbas Zafar’s Bade Miyan Chote Miyan, a tedious film about two men, whose only expertise lies in blowing up cars, saving India from a near-catastrophic crisis.

Zafar is no Siddharth Anand. The comparison is not to belittle the former but to underline that the strengths of the two filmmakers are distinct. Keeping his last work (Fighter) aside, Anand has displayed great knack in milking the tropes of the mainstream — like the way he introduces his cast, the conviction with which he goes ahead with bonkers plot twists, and the chemistry he creates among the male actors. Zafar, on the other hand, is as effective but different. Few like him can retain sentimentality as the subtext of chaos, or work their way through platitudes without draining them of joy.

The problem with BMCM (one among the thousands) is that Zafar tries to be Anand, fails, and in the process ends up abandoning his own style. His recent film is sorely unfunny, stylistically rigid, bafflingly boring and wastes the potential of two action stars coming together. Even steel advertisements have used the two-actor template with more inventiveness.

At this point, it would be only fair to share the story to back up this claim but I am resisting on two counts. Primarily because so much of it is forgettable that the only thing I remember from the outing is Tiger Shroff and Akshay Kumar using every excuse to flex their biceps and walk out of an explosion as if maintaining a step count was part of their contract. And, secondly, because that would involve giving out spoilers even when the biggest spoiler of BMCM (which a dear English-speaking friend of mine translated as Big Mister, Small Mister — something that made me laugh more than Zafar’s effort) is that it is a feature film when it could have been a Reel — and not the most engaging one out there.

But here are some details that did burn a hole in my mind:

Two self-respecting Indian soldiers, Captain Firoz (Kumar) and Captain Rakesh (Shroff), referring to each other as Bade Miyan and Chote Miyan.

An unhinged villain on the loose called Kabir (Prithviraj Sukumaran) sporting a black mask with golden decorations (that could have been part of an SUPW — that’s Socially Useful Productive Work for the uninitiated — project in school), and a leather jacket (that seems to have been picked up during a Black Friday sale).

A female captain (Manushi Chhillar) casually going to Shanghai for a piece of information — “the war has begun” — that literally would have fit on a piece of paper.

Alaya F single-handedly making a case for dissolving the manic-pixie prototype (she essays the role of a tech wiz, Pam, and falls flat on her face the moment she is introduced — what else are nerds if not clumsy?) and hitting astonishing decibel levels every time she says “guys” (which is, every time she speaks).

Manish Chaudhari, playing a high ranking officer in the Indian Army, given lines that are reactive shots in words — “If you insist”, “Do what you must”.

Ronit Roy looking like he has come straight from the set of another film where he is playing an army officer yet again.

An air of disinterest hangs over BMCM; every action set-piece looks derivative, every set feels imitative, and every song sounds the same. Even the problem at hand, which is a tepid mish-mash of Artificial Intelligence and cloning, only for it to be eventually tied to militant nationalism, evokes no newness. Anand’s Pathaan (2023) already introduced an anarchic villain who just wanted to wreak havoc with no allegiance to a nation. BMCM (written by Zafar and his frequent collaborator Aditya Basu) reiterates this with forceful dullness. Even the politics of the film seeks to cater to all sides (Pakistan and China are regarded as threats; mass brain-washing is predicted as a dystopian idea espoused by the villain, words like “Atmanirbhar” and a reference to Indian PUBG-rival game FAU-G are sneaked in) but ends up as a shapeless entity, pulped by the need to be pleasing rather than provocative.

Then there are the actors. As War (2019) evinced, Shroff is a competent action star who has the finesse and agility to invite conviction. He is watchable in moments when he is throwing his fists in the air but he also tries to act, a hubris that does not age well during the runtime of the film. There is also Kumar, who displays a nonchalance during stunts that can only be rivaled by Salman Khan. His placidity while jumping in the air, riding a bike or riding a horse, tears down every effort made by VFX. Chhillar is awkward and cagey while doing stunts, and Alaya F inflicts temporary hearing loss.

If the punches do not land, nor do the dialogues. It is incredulous how bad the spoken word in BMCM is, in the attempt to be funny. Kumar and Shroff share likable chemistry but they speak strictly in WhatsApp jokes. When Kumar taunts Shroff for being mature, the latter says, “Yes, like your FD”. Later, at a pivotal juncture when Kabir gets his moment and builds a crescendo about himself, he pauses before the punch line and mutters, “Because I am the best”.

It is easy to see the promise of such a film. The two actors are watchable on screen and can be potent if used well, especially Kumar. The few times BMCM shines is when he leans on his fun side. Like when he is asked to keep his ego aside and he struts his famous Hera Pheri pose, or when he glances at Kabir wearing a mask and offhandedly says, “yeh Batman kaun hain?” (“Who is this Batman”). But Zafar scarcely pursues this in his pursuit of making a film that everyone else is making. In the process, Zafar makes something that hardly feels like it was made by him.

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of OTTplay. The author is solely responsible for any claims arising out of the content of this column.