Satyajit Ray’s Ashani Sanket remains relevant amidst global food shortages

50 years since it was released in 1973, Satyajit Ray’s Ashani Sanket is a very relevant and important story for contemporary audiences

Last Updated: 11.26 AM, May 24, 2023

50 years since it was released in 1973, Satyajit Ray’s Ashani Sanket is a relevant and important story. Ray adapted Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s novels into Pather Panchali (1955) and Apur Sansar (1959). He returned to Bandopadhyay’s novel Ashani Sanket (1973) to make a colour film about the Great Bengal Famine (1943-44), a man-made famine that has been almost forgotten in annals of history.

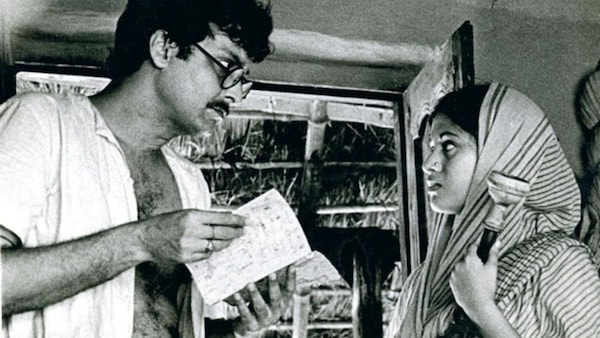

For Ray, making this film meant going back to his dependable leading man, Soumitra Chatterjee, to play Gangacharan Chakravarti, the village Brahmin, who is witness to a catastrophic, government-led food shortage and famine in pre-Independence India’s Bengal province. Farida Akhtar Babita plays his wife Ananga, a kind-hearted woman always willing to help those in need. There are multiple characters co-existing in a village, where Gangacharan, as its only healer, priest, and teacher, commands respect and manages to have a comfortable life with freebies and a steady income.

This film quickly changes pace and narrative when a massive food shortage, followed by a cholera epidemic, led to the death of over three million people. A scene cuts to a bomber aircraft flying over the lush, green fields and riverfront, where women enjoy the sight and sound. A distant war in Singapore that has Japan fighting against the British Indian empire makes for hookah-time chatter where Gangacharan updates the illiterate men of the village. Some mull if Singapore is a long distance from Midnapore, in one of the many subtle but powerful statements about the colonial rule that this film makes. For the subjects of British India, Midnapore and Singapore could well be interchanged. Only when the price of rice, Bengal’s basic food grain, begins to skyrocket, people’s behaviour here alters. Gangacharan learns to survive through his intelligence and smartness, even as he is stunned to see the decline in people’s destinies and the sheer helplessness that everyone faces. His wife adapts by working, foraging for food and suffering a traumatic attack.

Ashani Sanket is a poignant statement about the poor and vulnerable of a country ruled by an indifferent colonial master. To feed the armies fighting the Pacific War, civilian grain supplies from Burma and India were snatched away. By focusing on the struggles and moral battles of Gangacharan, Ananga, Biswas, the village rice dealer, a young widow and Chutki and a young bride, this film takes a macro-sweep of the all-consuming and dreadful famine. As film critic Pauline Kael describes, “Though its field of vision is narrow, more or less confined to the social awakening of a young village Brahmin and his pretty, naive wife, the sweep of the film is so vast that, at the end, you feel as if you’d witnessed the events from a satellite. You’ve somehow been able to see simultaneously the curvature of the earth and the insects on the blades of field grass.”

Ashani Sanket uses the contrast of verdant colours to reflect the sheer tragedy of this event. Nature, as it flourishes and grows through butterflies, insects, blades of grass and trees, did not create this shortage.Its cinematography, by Soumendu Roy, and music, by Satyajit Ray, captures the contrast of nurturing against starvation effectively. Working with limited budgets, Ray preferred to compose the music of his films in tandem with his writing. As people died of hunger, silence marked this starkness. But when women go to the woods to hunt for food, the music takes on a playful tone.

This film concludes with a social awakening and transformation of Gangacharan as he decides to break caste rules to preserve a dead person’s dignity. But it is not just one person’s story — in the fifty-first minute, a shocking scene gets the film’s core to the forefront. Barely clad, hunched, and tired women from a neighbouring village come begging for rice starch water, for there is nothing left to eat in theirs. This scene uses a line that induces dread for survivors, "Fen Dao Maa" (give me starch water). If not for Bandopadhyay’s novel and Ray’s film, the stain of the Bengal Famine would not have stayed alive and resonant in popular memory or art.

This film is about a famine that could have been avoided. Does that make it dated? If anything, it becomes all the more relevant. An October 2022 FAO and WFP report stated that near-famine conditions will prevail in four conflict-ridden hotspots this year — South Sudan, Yemen, Nigeria, and Ethiopia. Despite steady aid and food support from these global organisations, these regions could slip into famine as constant conflict and war have led millions to seek refuge elsewhere.

(Views expressed in this piece are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of OTTplay)

(Written by Archita Kashyap, she has tracked cinema, music, and entertainment for a long time. She loves stories in any format and believes that OTT is the next change-maker that will bring the best stories for everyone.)

Premium

Premium