A Ditty's Dizzying Rise: Interpreting The 'Naatu Naatu' Moment

RRR's Oscar for Best Original Song can be attributed to the aspect that epitomises it: a playful anti-colonialism as manifested in ‘Naatu Naatu’.

Last Updated: 12.43 PM, Mar 26, 2023

THE RECENT INTERNATIONAL ACCEPTANCE of SS Rajamouli’s RRR is clearly one of the more mysterious happenings in the history of Indian cinema’s reception abroad — with audiences outside the diaspora. Evidently, the shape of what is valued as ‘cinema’ globally has undergone a transformation — since the film was not critically acclaimed within India — and bafflement is still being expressed over ‘Naatu Naatu’ winning the 2023 Oscar for Best Original Song.

What we could say about RRR is that its significance in the West is not the same as its meaning locally, where it is taken to be a patriotic, anti-colonial film. Its anti-colonialism is rather like that of Lagaan in that it is not of the solemn kind (as in 1942: A Love Story) but playful, and Lagaan also did well with international audiences, being nominated for a Best International Feature Film Oscar. RRR was perhaps too flippant to be a candidate for Best Picture but it may be useful to study the success of ‘Naatu Naatu’ in the Original Song category to understand the success of the film as a whole.

On examining the list of films that have won the Oscar for Best Original Song, one finds that they correspond to a handful of types. The first kind is a big song from a very popular film — like ‘Somewhere over the Rainbow’ from The Wizard of Oz (1939) or ‘Que Sera, Sera’ from Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). The second is the song in a well-meaning award winner — even when the composition in itself is not memorable: like ‘Streets of Philadelphia’ in Philadelphia (1998) and ‘Jai Ho’ from Slumdog Millionaire (2008).

Animated films are apparently a separate category since they seem to be carried by songs, as in The Lion King (1994). Some dramatic films like Titanic (1997) or those featuring James Bond also have opening songs by a big musician that have been similarly honoured. What is singular is that songs from big musicals like The Sound of Music (1965) or My Fair Lady (1964) do not usually get picked. I would attribute this last fact to there being too much competition from within each film for only one to triumph.

The Best Picture Oscar, to reiterate what has already been suggested, is meant for very solemn films with a serious social/moral purpose. Action films or those from genres, even when they are classics, are not chosen for it. Hitchcock got it only for a relatively minor effort like Rebecca (1940) and Polanski’s Chinatown (1974) never got the award. There is some guilt evidently operating when masterpieces don’t fit the Best Picture requirements; therefore, so-called minor awards are lavished on them as compensation. Chinatown, for instance, received only the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay (Robert Towne).

This leads me to believe that RRR, being a popular success, received the award for the aspect that epitomises it: its playful anti-colonialism as manifested in ‘Naatu Naatu’. The Wizard of Oz, similarly, received only a minor Oscar for its music. RRR is not in the league of a classic, though I doubt that cinema anywhere meets the same standards that it once did.

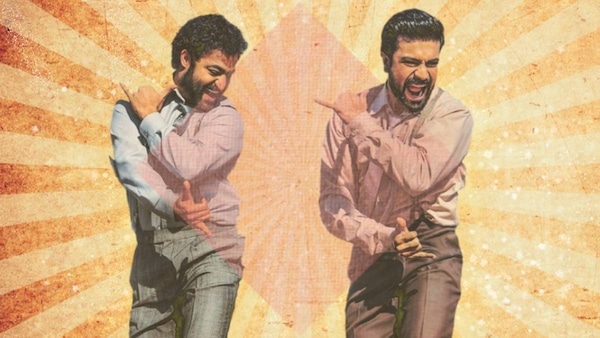

Coming to the success of ‘Naatu Naatu’ itself, I would suggest for a song in a major hit not solemn enough to be Best Picture, it must somehow epitomise what the film itself means to its audiences. It has perhaps little to do with the song’s actual value as vocal music. In India we take RRR to be patriotic and anti-colonial, but its anti-colonialism is manifested in Indians beating the British at dancing! Looking at the song, it is sung by two brown men in mock-colonial garb (complete with suspenders) in the presence of hostile white males and adoring women.

The brown man being more desirable than the white one (to white women) is also a trope propagated by other Indian patriotic films from Lagaan to Rang De Basanti (2006). This, being reverse racism, is acceptable in a milieu where political correctness prevails but also goes along with the playfulness of [their] anti-colonialism. Portraying the socially/racially oppressed as triumphing in areas dominated by the oppressors (like education or intellectual achievement) is also a political strategy frequently used across world cinema.

The superiority of the Indian dancers to the British is proved in RRR when ‘Naatu Naatu’ is shown to be demonstrably better than various Western dance forms like the tango and the waltz. ‘Naatu Naatu’ is not a known form with a defined set of movements but an exuberant demonstration of jumping skills — with able assistance from a choreographer alongside a film editor. The two male protagonists could not have replicated each other concurrently without such assistance; ‘Naatu Naatu’ is unlike a waltz with a predetermined set of movements that the partners are required to follow together.

RRR is using all these strategies to mount a light-hearted attack on colonialism — bearing no resemblance to the actual dealings of the British in India, just indicating broadly the political issues as cues to hang the narrative on. What I find interesting is that while the establishment tries to promote Visaranai or Koozhangal as representative of India by nominating it for the Best International Feature Film Oscar, that same audience apparently takes RRR to represent it! Notwithstanding the fakery in RRR, one cannot but be pleasantly surprised.

Apart from the colourful anti-colonialism in RRR, what may have attracted people to it in the West is its buddy angle. By and large when the nation’s past is the subject in any film, it is the male protagonist who is the national subject. However, RRR has two male protagonists trying to upstage each other and that merits speculation. My own supposition is that NTR Jr and Ram Charan represent two dominant (and occasionally warring) caste groups — Kamma and Kapu, respectively — and the film is an attempt to draw audiences from both groups by giving the two stars equal billing and putting them on the same side. But to Western audiences it means the return of the buddy movie (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid).

This would mean, as with its patriotism, that RRR is appreciated for very different reasons in the West. This could also imply that the film has no ‘formula’ that its director can rely on internationally for success. We learned that SS Rajamouli screened his even bigger film Baahubali to Western audiences and it produced no similar effect. He is planning a gigantic and patriotic Mahabharata — which can only be done with utmost solemnity — an approach that naturally precludes wide acceptance on Western screens.

MK Raghavendra is a well-known film critic

Premium

Premium