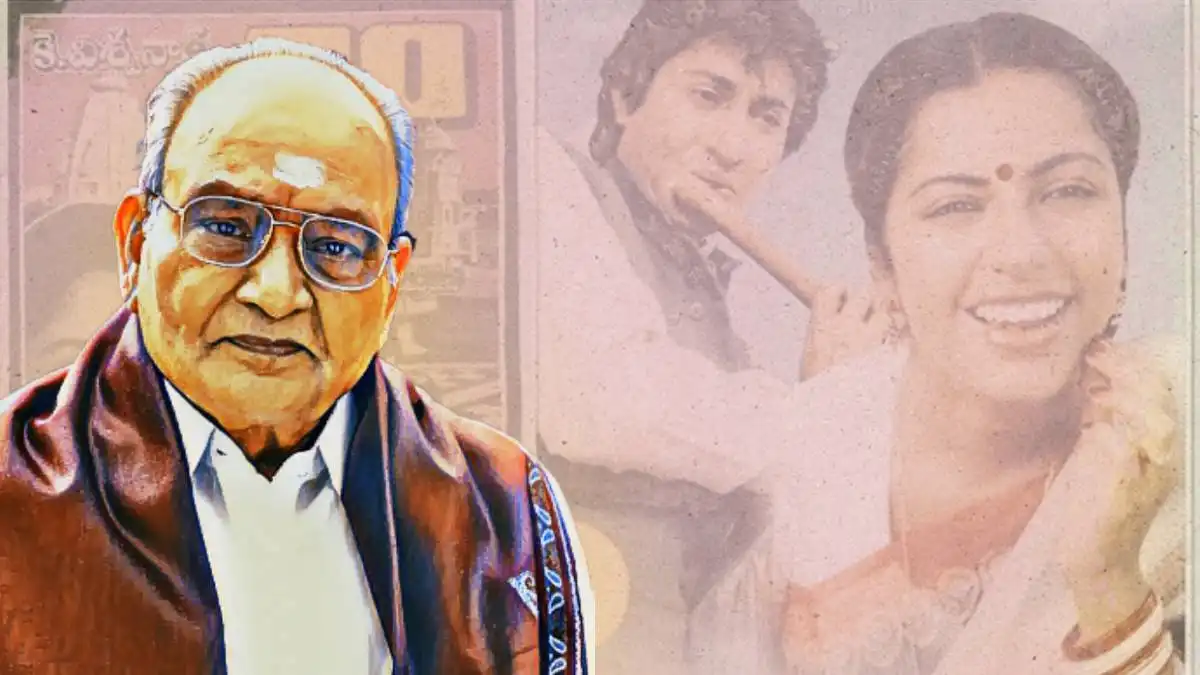

What K Viswanath's Legacy Means To Telugu Cinema

Mallik Thatipalli deconstructs the legacy of a towering auteur.

Feb 06, 2023

THERE IS A SCENE in K Viswanath’s Sruthilayalu (1987; Telugu) that never ceases to amaze me: When Sita (portrayed by the lovely Sumalatha) wants to tell her son Srinivas that the alcoholic Narayana Murthy (Rajasekhar) is his father, she simply takes a framed picture of Shiva, Parvati and Ganesha from the wall, and says, “You are Ganesha and he is Shiva”. Such touches were the hallmarks of Viswanath’s works, spanning nearly three decades. This is also key to understanding the auteur’s towering influence over the Telugu film industry for nearly half a century.

Viswanath was the visionary behind Kamal Hasan’s iconic performance as a struggling dancer in Sagara Sangamam Chiranjeevi’s vulnerable turn in Swayamkrushi, Venkatesh’s poised act in Swarnakamalam and Mammootty’s jealous character in Swati Kiranam. He saw the actors beyond the stars and gave them space to explore their craft, in the process immortalising them at their best on the silver screen.

Viswanath’s legacy remains unparalleled in the annals of Telugu cinema. From Jayaprada and Radhika to Vijayashanti and Bhanupriya, he gave roles of a lifetime to his leading ladies. Draping them in the local weaves, giving free rein to their expressive eyes and their training in classical dance forms, his reverence and respect for his female actors set him apart. A generation of leading ladies owed their career defining roles to him, roles that painted them as individuals with strengths, flaws and agency — traits that were fast vanishing when it came to women in the Telugu cinema of the 1980s and ‘90s.

His stories brought the Indian classical arts into the “mainstream” popular cinema: With frequent collaborator — the great KV Mahadevan — providing music based on traditional ragas, Viswanath made classical music accessible to the wider public. Shooting in stepwells and temples across India, each frame highlighted the rich architectural heritage of our country whilst capturing them for posterity.

The genius of Viswanath lay in his approach to cinema — it remained accessible, while showing the unattainable. It helped people believe that the pursuit of the divine resides in the pursuit of the self… through art, through music, and mostly through love. His movies were comparable to the gentle rays of the sun on winter mornings. That isn’t to say he overlooked the aspects of entertainment and storytelling. For instance, few directors would even dream of showcasing the love triangle between a blind flautist (Sarvadaman Banerjee), an escort (Moon Moon Sen) and a mute painter (Suhasini) as Viswanath did in Sirivennala moulding it into an unforgettable and epic collage of unrequited love, bolstered by understated performances.

Medium & Message

Widow remarriage, elder neglect, rehabilitation of devadasis, addressing casteism — Viswanath tackled various social messages through his prolific output and conscious cinema. In Shankarabharam the protagonist is a renowned Carnatic musician who masters the titular raga. A tyrant when it comes to his musical compositions, he is generous when the daughter of a devadasi wants to learn music, inviting an otherwise marginalised woman into the innermost sanctum of a callous society. In Saptapadi, a husband sees in his wife the avatar of the goddess he idolises, paving the way for her to reunite with her flautist lover from a different caste. In movie after movie, Viswanath’s propensity to take pressing socio-cultural issues and make them palatable through the medium of cinema, is a revelation.

In the layered Subha Sankalpam the idiom and imagery remain the sea — the living heart of its protagonist, a fisherman played by Kamal Haasan. The lilting folksy tunes, lush landscapes, and the travails of a harsh livelihood have never before nor since been depicted in as authentic a manner in Indian cinema. Such was Viswanath’s mastery: To shine the limelight on those relegated to the sidelines, even if it was only for the three-hour runtime of his film/s.

Sense & Sensibilities

Viswanath invariably equipped his female characters with integrity, an unwavering moral compass, and compassion. A widow in Sagara Sangamam does not hesitate to pretend that her husband is alive, in order to help her soulmate. A besotted wife in Swayamkrushi understands and respects that she isn’t first in her husband’s life. These women operate within the limitations posed by both society and the men they love — yet thrive in spite of them.

Even minor characters have the freedom of choice, a concept Telugu cinema has never really understood. In Swarnakamalam a penury-stricken father asks his daughter for her permission before agreeing to a marriage proposal. In Swatimutyam, a woman who washes clothes for a living, helps the lead character to understand the importance of consummation of a marriage. Sex workers, as seen through Viswanath’s lens, are always people and never caricatures.

Viswanath’s legacy in Telugu cinema remains as impactful today as in his heyday. His movies remain a benchmark for their cinematic finesse, strong storytelling, and their use of music as an instrument in storytelling. Repeated showings on TV channels have only exhibited his genius to a younger generation and proved the timelessness of his themes.

As Indian cinema (especially from the south) is making ripples with its unbridled machismo and adrenaline infused storylines, Viswanath’s movies showcase softer hues. Where disabled characters could play the lead, music could be soulful, and masculinity meant respecting your beloved’s choice in loving someone else.

Movies, for many, can be a refuge and a haven from the vagaries of life. K Viswanath’s were both. They were also mirrors for society — that might help it understand itself, and even seek redemption.

Share