Evil Does Not Exist Choreographs A Mismatched Dance Of Economy & Ecology

Ryusuke Hamaguchi's film reminds us of the unforgiving beauty of the natural world we live in, even if urbanisation and industry sever our connection to it.

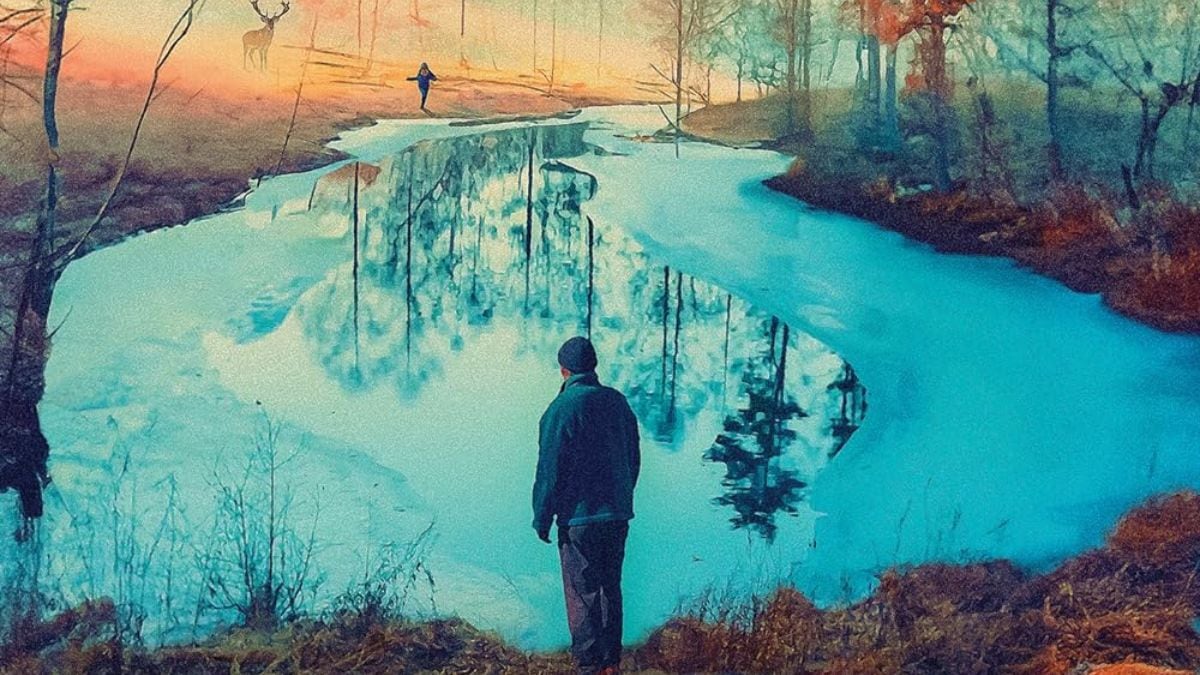

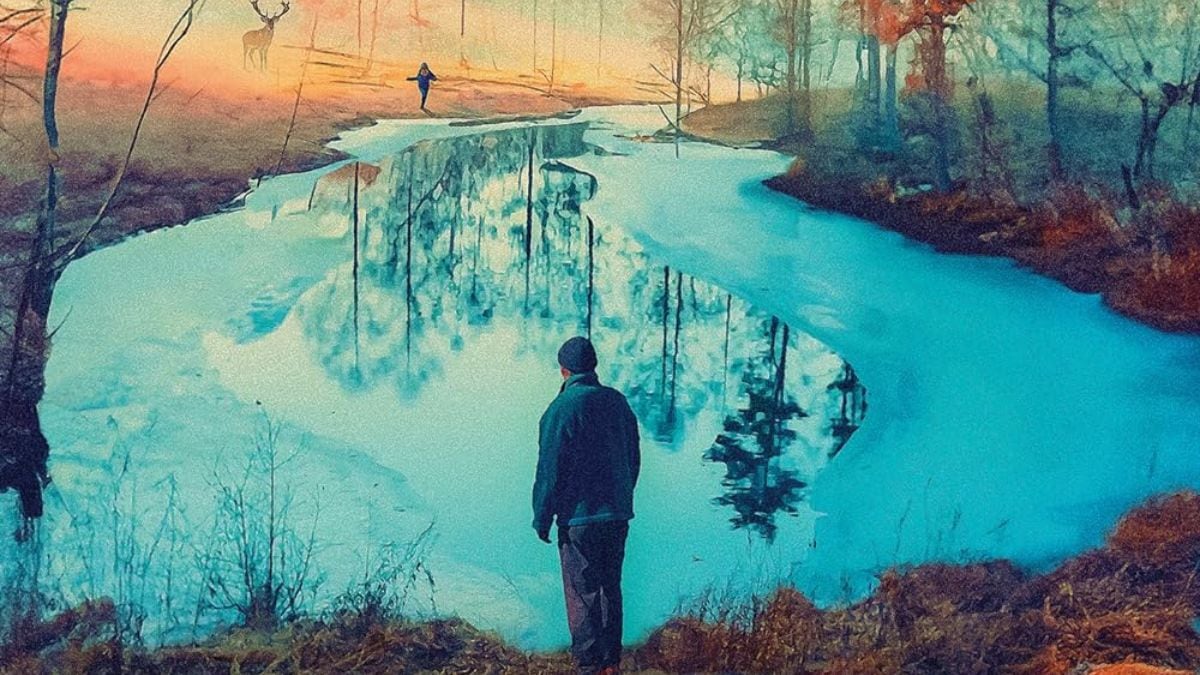

Cover poster for Evil Does Not Exist.